OK, so why does Brazil speak first?

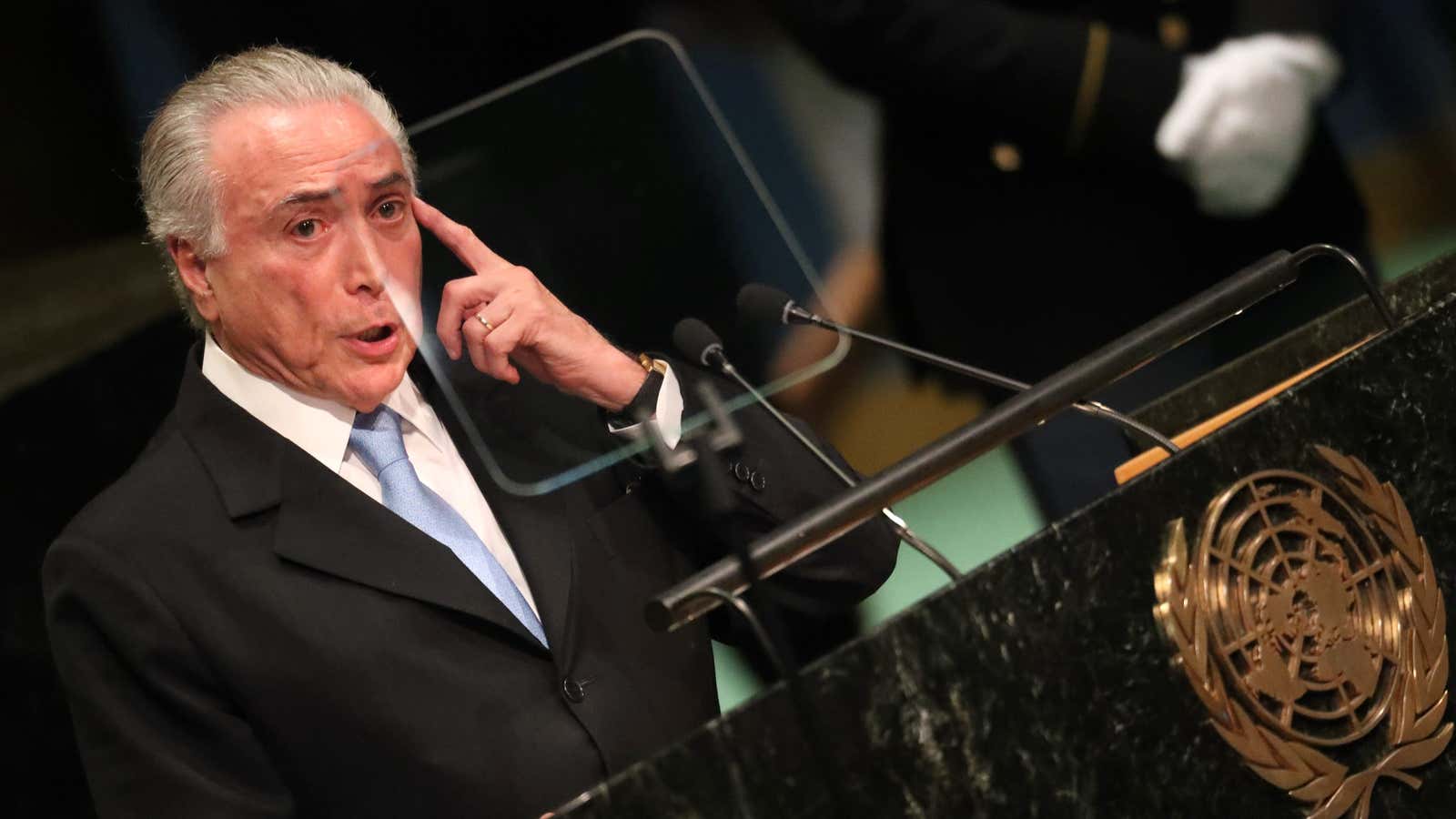

Brazil doesn’t seem the most logical country to open the five-day-long “general debate” at the United Nations General Assembly every year. It’s not a Security Council member; it doesn’t come first alphabetically; and it’s not the host nation. So why will Michel Temer, the country’s embattled president, be the first head of state to speak?

The reason is suitably charming and archaic. “In very early times, when no one wanted to speak first, Brazil always…offered to speak first. And so they have earned the right to speak first at the General Assembly,” Desmond Parker, the UN’s protocol chief, told NPR in 2010. Brazil has done so since the 10th UNGA in 1955.

After that comes the United States (the host country), and then it gets complicated: “For all other member states, the speaking order is based on the level of representation, preference and other criteria such as geographic balance,” the UN explains.

In practice, that means that if your head of state doesn’t come, you get shunted behind all the ones that do. But what if you’re the head of government (like Britain’s prime minister or Germany’s chancellor) and your country’s head of state is a monarch or some other figurehead? Sorry—also to the back of the line. Foreign ministers or other deputy ministers tend to come last.

How long can they speak for?

As long as they please. In theory, there’s a 15-minute maximum, but that’s only voluntary and many leaders pay no attention to it. US president Barack Obama, for example, went on for 47 minutes last year, 43 minutes in 2015, and a breezy 39 minutes in 2014. The longest UN speech ever? Probably Indian defense minister V.K. Krishna Menon, who went for an astonishing 7 hours 48 minutes in 1957—but at the security council, not the general assembly. The longest UNGA speech on record is Fidel Castro with 269 minutes in 1960. Also of note: Nikita Khrushchev (140 minutes, 1960) and Muammar al-Gaddafi (96 minutes, 2009).

Do any non-UN states attend?

Yes, the European Union sends a speaker, as do the Vatican and Palestine, which are “non-member observer states.”

What languages can I watch them in?

Speeches are translated into Arabic, Chinese, English, French, Russian, and Spanish.

What are they debating?

Yes, it’s called the “general debate,” but there’s no real debating, nor any “yay” or “nay” votes. Leaders can pretty much talk about whatever they want, which usually means whatever’s important to their governments right now. In some years the UNGA’s “theme” (like refugees or the Sustainable Development Goals) does inform the topics, but don’t expect much steerage from this year’s impenetrably vague “Focusing on people—Striving for Peace and a Decent Life for All on a Sustainable Planet.”

How long does it last?

This year the debate begins at 9am on Tuesday, 19th September and finishes on Monday, 25th September.

Why does anyone even care?

Well, aside from the possibility of an entertainingly mad speech like Gaddafi’s, there’s a lot more that goes on outside the general debate, from meetings in the UN itself to a plethora of side events—plus, of course, it’s a rare opportunity for world leaders to get together for private chats. Here’s a guide to the key issues on the UNGA agenda this year, and our pick of the most interesting other meetings.

Correction: This article has been updated to reflect that V.K. Krishna Menon gave the longest speech in UNGA history, not Fidel Castro.