The Swedish Academy awarded the Nobel Peace Prize to the International Campaign Against Nuclear Weapons (ICAN) today, in what it said was an “encouragement” for countries to get behind the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons being pushed at the United Nations.

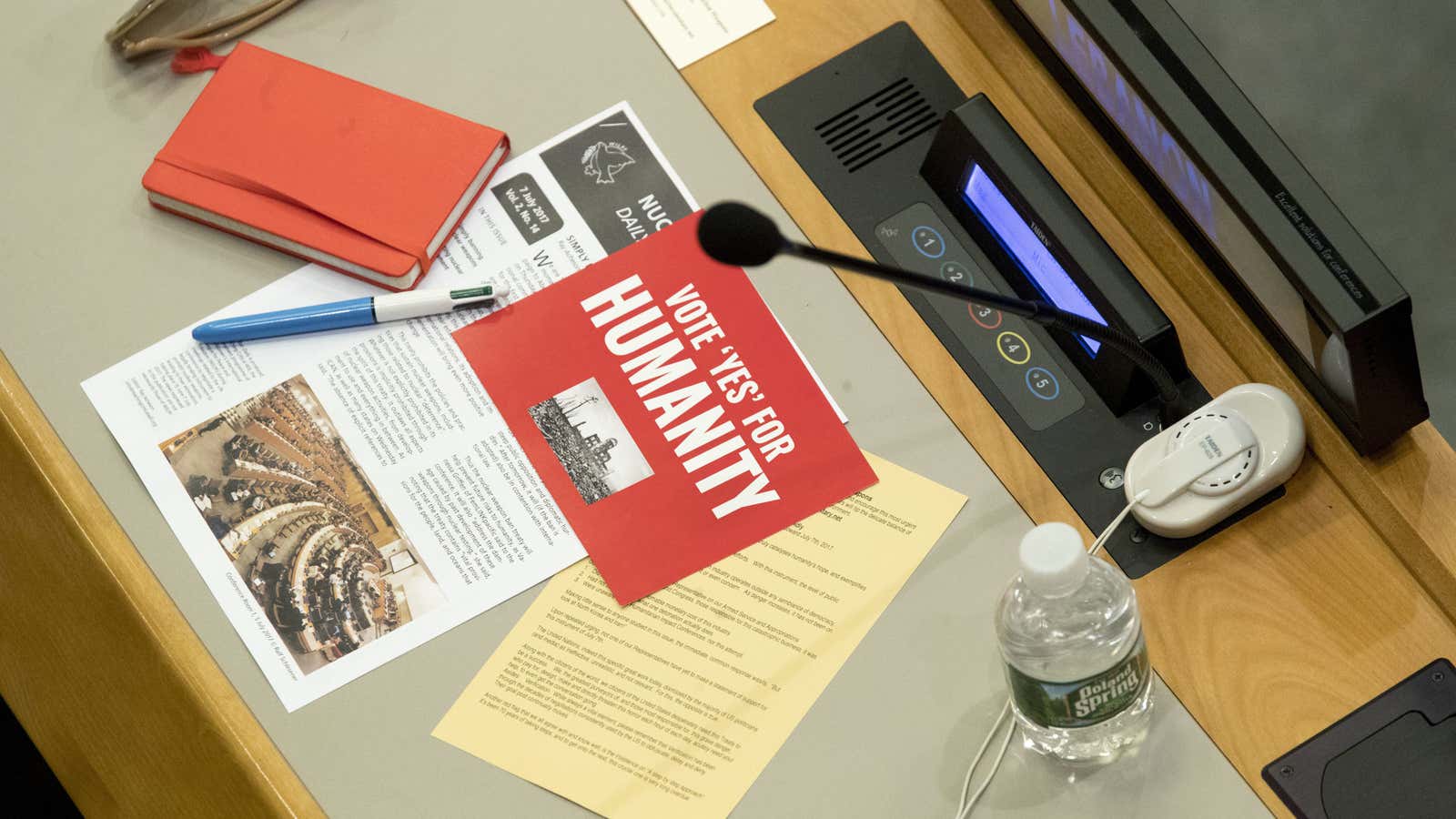

In July, 122 countries voted (paywall) for the treaty, which would ban any country from using nukes. Fifty-three countries have signed the treaty so far—a process that started during UN General Assembly week on Sept. 20. Once more than 50 have ratified it, the agreement becomes international law.

The treaty is “an important show of intent from the international community. It’s an important stigma on nuclear weapons that they be banned internationally like other weapons of mass destruction, such as chemical and biological weapons,” says Tom Collina, policy director at the Ploughshares Fund, which aims to eliminate nuclear weapons from the planet.

So, the US and others will now have to get rid of nukes?

No. There’s a sizeable catch: None of the countries that actually have nuclear weapons is among the 122 backers of the treaty—in fact, they’re all vehemently opposed. Right after the vote in July, the UK, the US, and France released a joint statement, saying, “We do not intend to sign, ratify or ever become party to it.” That’s why analysts like Collina are calling it only a “statement of intent.”

What’s the point of the treaty, then?

Its main aim is to change not international law but international norms, says Stewart Patrick, director of the International Institutions program at the Council on Foreign Relations in New York.

“This campaign is an effort to make these weapons declared, in a normative or moral sense, beyond the pale: in other words to say that they have no place in humanity and civilization,” Patrick said. Once the vast majority of the world has signed on, the nine countries that have nuclear weapons will look like moral degenerates and will be pressured into culling and finally destroying their own stocks. Or so the theory goes.

For proof that this will work, the treaty’s advocates point to the Ottawa Landmine Convention in the 1990s. The overwhelming majority of the world has signed it. Massive powers like the US, Russia, and China are still holdouts. But its supporters say that doesn’t matter: There’s now a stigma against landmines, and those countries can expect an enormous backlash if they use them.

So why don’t the nuclear powers just agree to the ban?

They would argue that nuclear weapons are a different kettle of fish to landmines, which, for all their horrors, aren’t an existential threat. The US and others say that having nuclear weapons protects the world from rogue states like Iran and North Korea. As America’s UN ambassador, Nikki Haley, argued earlier this year (paywall), “We have to be realistic. Is there anyone who thinks that North Korea would ban nuclear weapons?”

Collina calls Haley’s argument “nonsensical.” “It’s not like the US would unilaterally disarm and hope that everyone else did—it would be a coordinated process,” he says. “Of course, the US would never give up nuclear weapons in the face of a threat from North Korea, but the point of an international ban treaty is that all nations would get together and figure out together how to get rid of them.”

“Why does North Korea want nuclear weapons?” he adds. “They want them because they perceive a threat coming from the US. A negotiated settlement could solve that.” As evidence that this would work, he points to the 1994 US-North Korea treaty, in which Pyongyang agreed to pause its nuclear program as long as Washington guaranteed it wouldn’t threaten North Korea militarily.

There’s another reason that countries are loath to give up their nuclear arsenals: power. Having nuclear weapons “is one of the things that distinguishes great powers from not-great powers,” says Patrick. So, it’s going to take a lot to get any one of the nuclear nations to voluntarily part with them. If one did, however, that could prove a tipping point, Patrick says. Unless pro-disarmament British opposition leader Jeremy Corbyn gets elected, though, that doesn’t look likely any time soon.

What exactly will the treaty achieve, then?

First, it might combat the threat of a “cascade effect,” Patrick says. “Say if Iran were to produce nuclear weapons and the US security guarantee were no longer enough for South Korea or Japan. You could get runaway nuclear arms.” If countries had already signed up to a nuclear ban, it might be more difficult for politicians to sell that to their publics.

Second, even if the treaty doesn’t abolish nuclear stockpiles outright, it might help shrink them. The US and Russia have vastly fewer nukes than at the end of the Cold War, but this reduction slowed (paywall) as relations cooled between former president Obama and Russia’s Vladimir Putin, and now Donald Trump is actively pro-nuclear modernization. The treaty “is a message to nuclear-weapons-possessing states that time running out and they need to get serious on this,” says Collina.

If the rest of the world can keep the pressure on nuclear powers to reduce their stocks, perhaps one day they’ll finally choose to get rid of them. That’s the hope. But even activists admit that’s unlikely any time soon. “We’ve been working towards the elimination of nuclear weapons for 70 years now, so it’s a long-term process,” says Collina.

Correction: An earlier version of this story said the weapons ban treaty enters into force after 50 states sign it; we omitted “and ratify”. (Here’s the treaty text.) Apologies.