Apple’s iPhone SE has reached the same, exalted evolutionary pinnacle as the cockroach

Cockroaches have been around for 300 million years. After emerging in the Carboniferous period (affectionately named the Age of Cockroaches), the creatures have scurried along pretty much unscathed and unchanged. They’ve endured the arrival (and departure) of the dinosaurs, massive rise (and fall) of sea levels, steam engines, nuclear power and, more recently, cans of Raid. Cockroaches are a pinnacle of evolution.

Cockroaches have been around for 300 million years. After emerging in the Carboniferous period (affectionately named the Age of Cockroaches), the creatures have scurried along pretty much unscathed and unchanged. They’ve endured the arrival (and departure) of the dinosaurs, massive rise (and fall) of sea levels, steam engines, nuclear power and, more recently, cans of Raid. Cockroaches are a pinnacle of evolution.

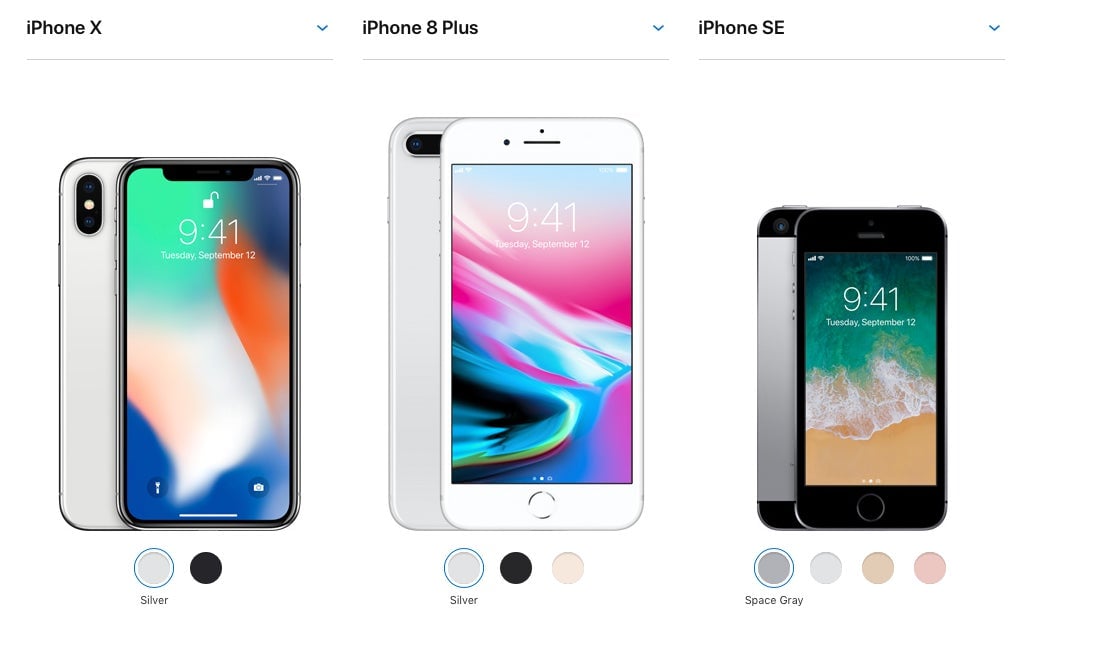

On a less grand scale, you might add the design of the iPhone SE to the list. As Apple touts its $699 iPhone 8, and the upcoming $999 iPhone X (read “ten”), only a step away from making phones nothing but a slab of glass, it’s worth reflecting on the virtues of the predecessor that may outlive them all.

Last year, Apple sold 215 million of its phones. The $349 iPhone SE, launched in March 2016, quickly claimed a healthy share of those sales: 9.8% of all sales by the second quarter of 2016. The SE has proven to be the culmination of the most timeless iPhone designs Apple has produced, and it may remain so for a very long time. Its basic design comes directly from the iPhone 5 launched in 2012, which rounded off the iPhone 4’s boxy edges and dropped the glass backing. While smaller and less powerful than its successors, the SE is the ur-machine, the blueprint for a device that has come to define the digital age. As Wired notes, the phone fits the advanced electronics of its successors in the exterior of its predecessors.

The SE may long defy the craze for larger, feature-heavy phones. Apple’s own seem to agree.”We’ll probably never stop making the SE or something like it,” said a salesperson at San Francisco’s Apple store on Sept. 22, praising the decision to stick with the SE. “Some people just need a phone.” I think it’s far more than that.

Give me less

If I give up on the SE design, it will be because something fundamental has changed about how we use our pocket computers. My 2016 model has all the necessary electronics in the correct physical form to fit my hand or slip inside my pocket. When I draw it out, people glance over comparing it to the oversized machine in their own hand.

My plan wasn’t to buy an SE. Apple was releasing the iPhone 7, its latest and greatest device. I entered Apple’s Union Square store willing to splash out on a $600 purchase. The store’s two-story glass and steel wall was open to a crisp San Francisco spring day. The sales person walked me through each new model. A pressure-sensitive screen instantly pulled up shortcut menus. A faster A10 chip cut out annoying time lags. The expansive size made watching videos comfortable.

As I put each device down, I realized none did their job better than the iPhone in my pocket. They did more, yes, but not necessarily better. I’m not sure it’s so different with the iPhone X. Its 5.8″ Super Retina HD display is already beyond the ability of the human eye to differentiate between my SE’s 4” retina screen. A bigger screen? I want to deter casual phone usage (“All screen activities are linked to less happiness, and all non-screen activities are linked to more happiness,” reports The Atlantic). Doubling memory? I’ve got the cloud and WiFi. Wireless charging? Great, once chargers are ubiquitous. I may use face recognition one day, and Apple’s new water-resistant models are tempting, but I’m fine leaving my phone behind where it might get wet, or limiting the surveillance potential of my devices.

Naked design

Some in Silicon Valley like to say that great design means stripping away the inessentials until nothing else remains. It’s what Evan Williams says inspired him to build Twitter after years toiling on Blogger (sold to Google in 2003). ”I spent all of my time trying to add things to it,” he said, which he came to see as the wrong strategy. Strict design limits (e.g. 140 characters) came to define his companies’ products from Twitter to the publishing platform Medium.

Of course, every generation rediscovers this design principle. French author and aviator Antoine de Saint-Exupéry articulated it decades before in Airman’s Odyssey about his days as a pilot before writing The Little Prince:

Have you looked at a modern airplane? Have you followed from year to year the evolution of its lines? Have you ever thought, not only about the airplane but about whatever man builds, that all of man’s industrial efforts, all this computation and calculations, all the nights spent over working draughts and blueprints, invariably culminate in the production of a thing whose sole guiding principle is the ultimate principle of simplicity?

It is as if there were a natural law which ordained that to achieve this end, to refine the curve of a piece of furniture, or a ship’s keel, or the fuselage of an airplane, until gradually it partakes of the elementary purity of the curve of a human breast or shoulder, there must be the experimentation of several generations of craftsmen. In anything at all, perfection is finally attained not when there is no longer anything to add, but when there is no longer anything to take away, when a body’s been stripped down to its nakedness.

When it comes to phones, my perfect is different than yours. I’m not a gamer. I don’t watch hours of streaming video. I’m eager to adopt new technology, but it’s simplicity, ease, speed, functionality, and beauty I’m after. I want as much elegance as I can get between my metal and glass. For me, doing without is having more of what I want.

One day I’ll leave the iPhone behind. If Apple’s new $5-billion campus is an indication, that time may not far be off. Apple has descended into the minutiae of aesthetics and luxury without obsessing over the perfect user experience that so consumed its founder Steve Jobs. It’s telling that the campus boasts leather seats and marble staircases yet has no chairs to sit in its lobby or a daycare for its employees.