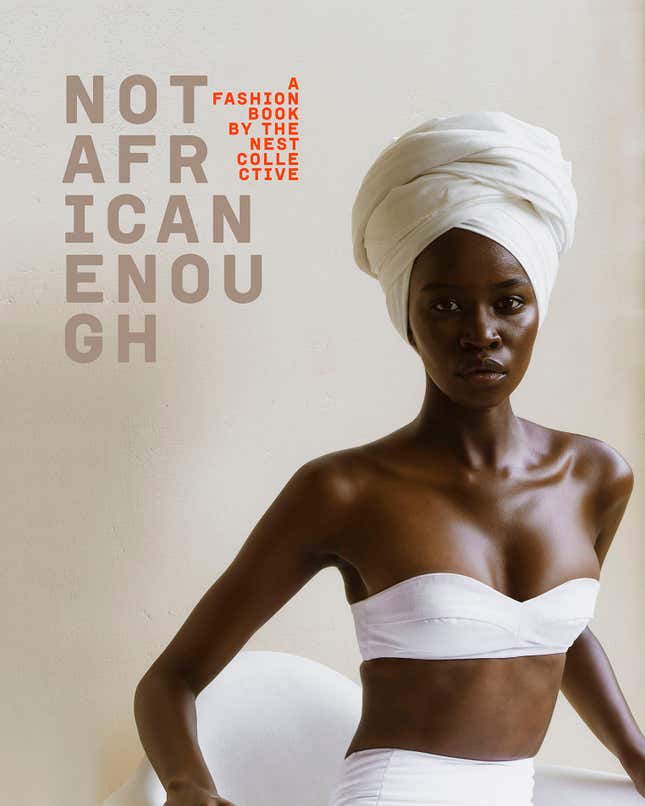

In Not African Enough, a collection of photography and essays on Kenyan fashion, one designer bemoans what she calls the “vicious cycle of wax print.” The bright, intricately patterned fabrics that have come to define African textiles are not from East Africa, nor really from Africa at all. Yet, almost every one of the 14 designers featured in the book describes feeling pressured to incorporate wax print into their work.

“All the prints come from China or the Netherlands, and they’re designed in those countries as an imitation of what they think we think is African,” says Firyal Nur, who started the brand Nur.

The book, published this month by the Nairobi-based arts collective Nest, features the work of local designers who are challenging reductive ideas of what makes up “African” fashion. It’s not just about clothing.

“‘Not African enough’ is a derogatory term routinely lobbed at artists, creators and thinkers who step outside the narrow confines of what the world—and Africans—think it means to look, talk like, think like and be an African,” says Sunny Dolat, a stylist and designer who took many of the photos for the book.

The book features designers whose work ranges from leather and casual wear, to bridal gowns, and jewelry made from local minerals. Dolat says, “This questioning of ‘Africaness’ is a thing all the designers have been up against at one point of their careers. They have reflected about it as individuals and have found answers in their work and in their identity as creatives.” These are some of their answers:

Firyal Nur Hossain

Hossain, born in New York and raised in Switzerland, recounts in Not African Enough how she started out in the industry designing with wax prints. After a period of avoiding the fabrics, she now incorporates them in her clothing line, Nur, that focuses on “universal elements” ranging from “traditional and contemporary, tribal and urban.”

“My first collection was almost completely wax print. I have a love-hate relationship with wax print because I feel like it’s not a great portrayal of our industry—we don’t manufacture those prints here…. But I love them, and seeing people wearing print is always a really beautiful experience for me. I’m trying to understand how I can take what I love from them and reflect that without being part of this vicious cycle of wax print,” Hossain writes.

“When it comes to ‘African,’ everybody is a critic. I think it’s good to take a step backwards and be less critical of everything—why can’t we just explore you know?”

Kepha Maina

Maina, a Nairobi-based women’s wear designer, started off buying clothes from the city’s massive second-hand market, Gikomba, deconstructing them, and creating new pieces. His early inspirations came from Western styles. “I felt like I was just copying foreign things, following trends,” he writes. At the same time, traditional African fabrics like Kitenge and Ankara didn’t speak to him. Today, his clothing focuses more on the fantastic, through folds and panels that resemble armor.

“Kitenge and ankara are alien to me. The only time I’ve seen my mother wearing kitenge was on her wedding day in 1991…. So ‘African print’ is not something I have a connection with. I worked with it later when I started out as a designer because of that conflict about African designers having to use it to qualify as Africa but it was really distant to me.”

Ami Doshi Shah

Shah, a trained silversmith and jeweller, works with local materials from copper and rope to leather and semi-precious stones. She describes resisting the over-the-top West African aesthetic that many people expect from African fashion with understated pieces that can stand on their own.

“We’re not extravagant as Kenyans. We’re culturally trained to never be over the top because there’s no need, you know? In West Africa, extravagance is a cultural statement. Here, toning it down is the statement,” she writes. “As Kenyan designers, do we really need to include wax print in everything we do? It’s the easiest way for us to define ourselves as Africans, but it ignores the fact that we’re influenced by everything around us.”

M+K

Founded in 2016 by Muqaddam Latif and Keith Macharia, the M + K Nairobi clothing line relies on local artisans for embroidery, hand-beading, and leather working. “When we look at the new-age Kenyan designer, we’re seeing a strong design aesthetic that’s forming with wearability in mind; it’s not all conceptual.”

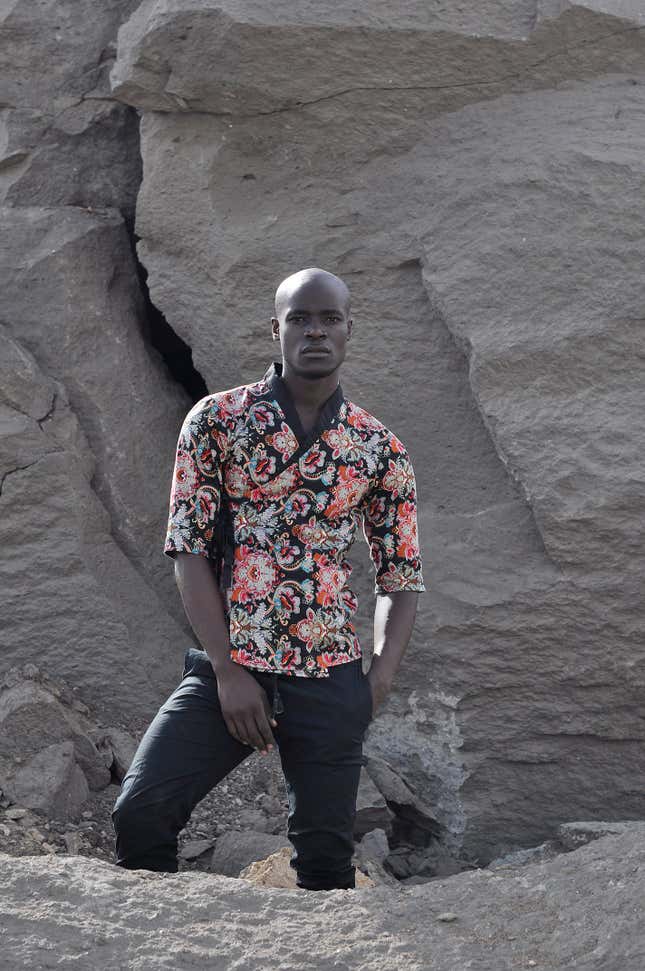

Munga

Basics and street-wear designer Munga has been accused of being “unmanly” for using varying lengths and drapes in his clothes to be worn by men or women. “I do enjoy working around our conservative ideas about what a man can wear,” he writes.

“I’m really interested in exploring what the unique character of Nairobi is as I play around with street-wear—what we as Kenyans can do with youth, movement, and urban freshness; when we mix classics with trends and anti-trends.”