Concepts in psychology that even the experts get wrong

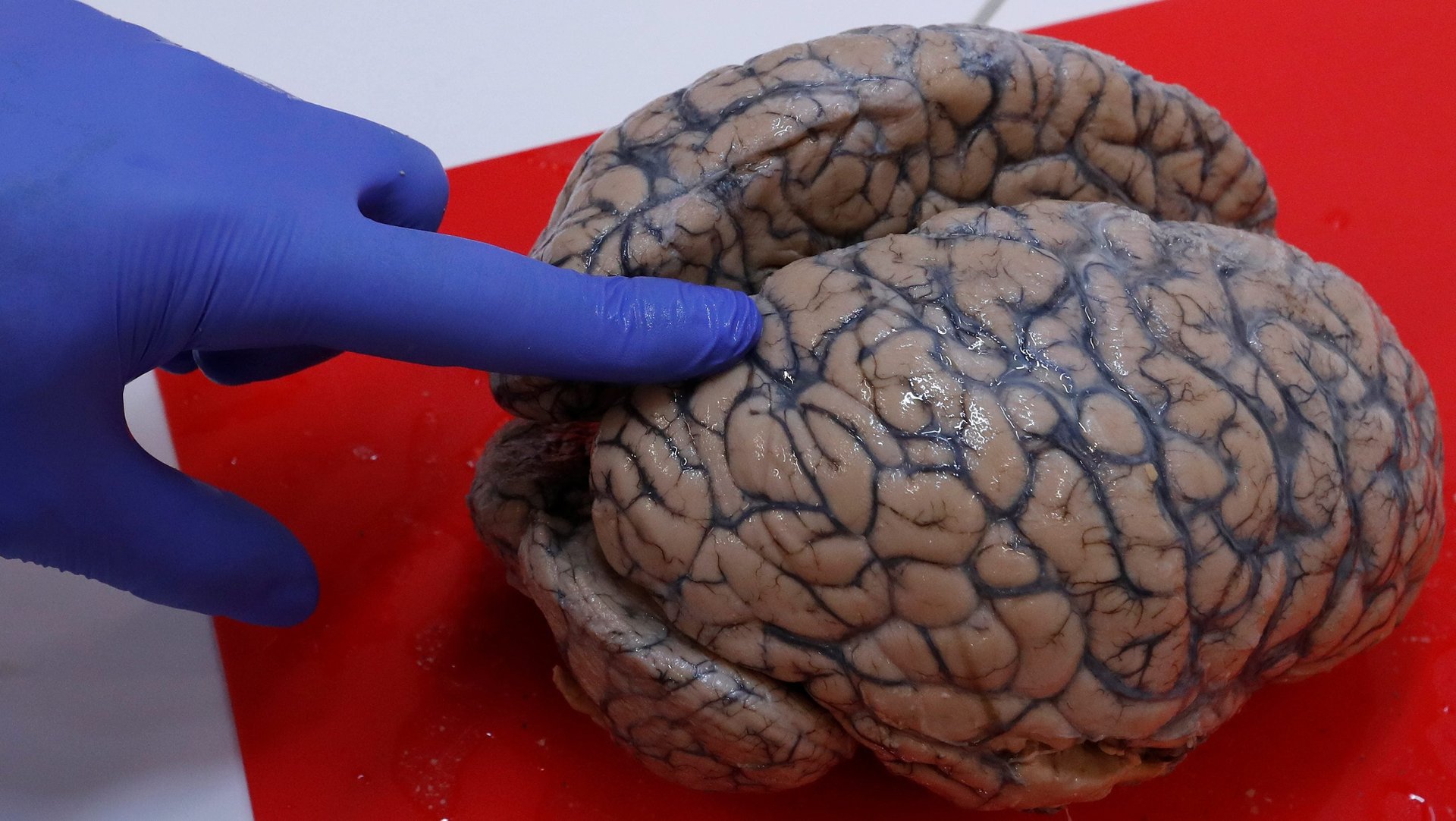

One challenge to treating a mental health problem is that a person can’t just point to a part of their body and say, “This hurts, please fix it.” Without a diagram to label, experts who study and treat mental health problems have to develop concepts and metaphors in order to communicate, and it can, understandably, get very complicated.

One challenge to treating a mental health problem is that a person can’t just point to a part of their body and say, “This hurts, please fix it.” Without a diagram to label, experts who study and treat mental health problems have to develop concepts and metaphors in order to communicate, and it can, understandably, get very complicated.

In July, five psychologists published a review of concepts they say confuse the psychology field. The team was led by Scott Lilienfeld, from Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia, who helped compile a similar paper in 2015. Together the two lists contain 100 frequently misused and confusing words and word-pairs (like “obsession and compulsion”), with explanations on how to use them correctly.

The words and concepts weren’t selected systematically but rather were chosen based on the researchers’ experiences as teachers, textbook writers, journal editors, and academic writers who also write for popular audiences, and what they observe other experts doing. The goal was to provide a compendium of words that everyone—academics, journalists, and casual readers of pop psychology—could use some clarification on. Here are a few examples:

“hardwired”

Now a common phrase in news headlines, TED Talks, and blurbs for books about psychology and human behavior, “hardwired” originally referred to rigid cables, as opposed to flexible ones, in electronics. Its application was then widened to any computer hardware specifically wired for a function that couldn’t be changed.

But recently, its overuse as a metaphor for the mind has gotten a bit out of hand. According to the researchers, few psychological abilities are actually “hardwired.” They write:

The term “hard-wired” has become enormously popular in press accounts and academic writings in reference to human psychological capacities that are presumed by some scholars to be partially innate, such as religion, cognitive biases, prejudice, or aggression. For example, one author team reported that males are more sensitive than females to negative news stories and conjectured that males may be “hard wired for negative news.” Nevertheless, growing data on neural plasticity suggest that, with the possible exception of inborn reflexes, remarkably few psychological capacities in humans are genuinely hard-wired.

“steep learning curve”

When taken literally, this phrase means the opposite of how we use it in everyday language. A graph that plots how long it takes someone to learn something would show mastery on the Y-axis against time or experience on X-axis. So a steep curve, technically, would actually represent a thing that took less time to master.

The commonly deployed phrase “[x skill] has a steep learning curve” is usually intended to mean that the skill is difficult to learn. Perhaps this usage is drawn from the idea that the skill must be mastered in very little time—in other words, the skill requires a steep learning curve and is therefore difficult. Or it could simply be that we associate steepness with hard-to-climb mountains, and from there we get “steep learning curves,” which make sense metaphorically but maybe not so much literally.

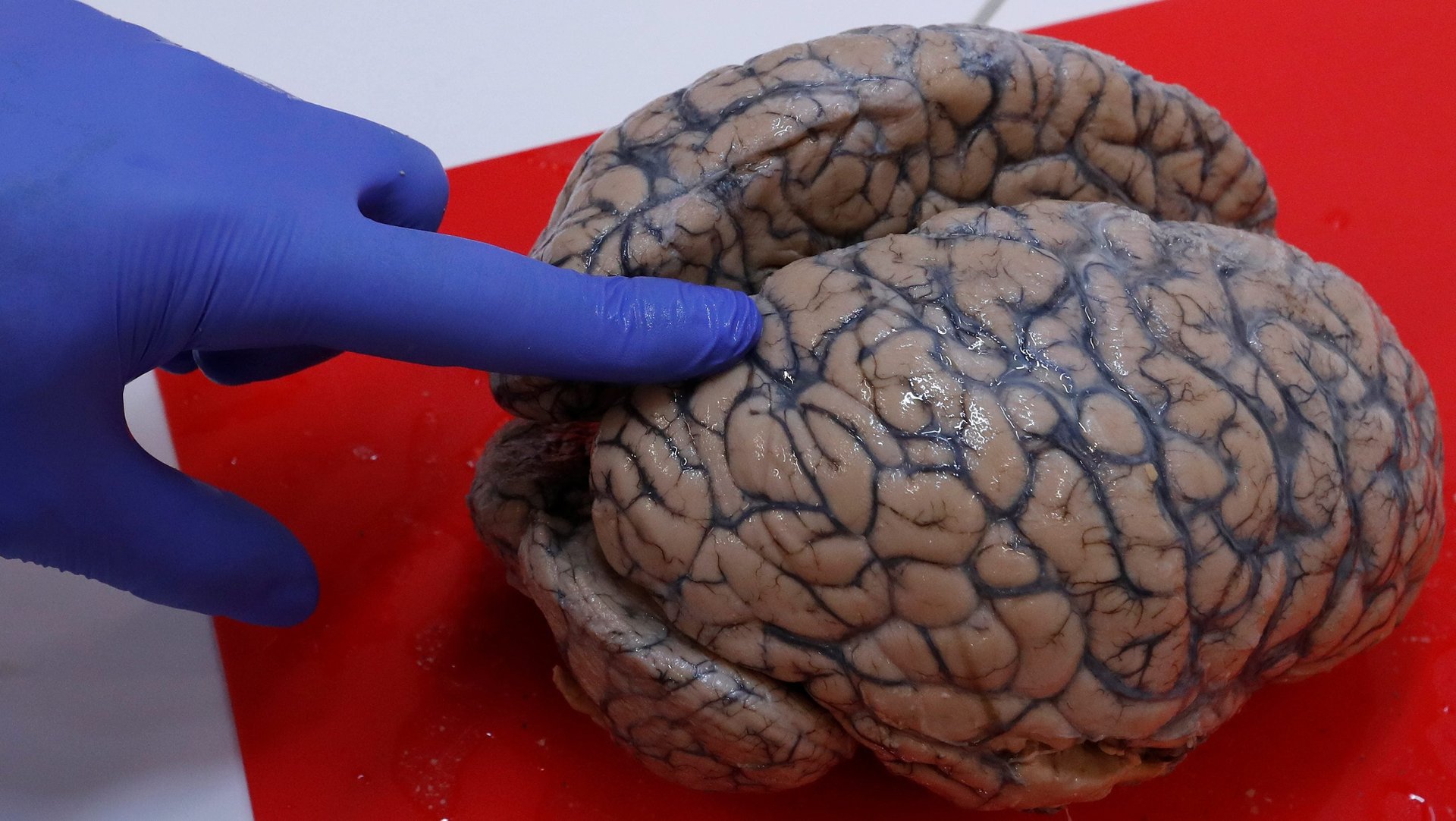

“brain region X lights up”

When scientists say a part of the hippocampus “lights up,” they generally mean that in an fMRI, that region of the brain appears lit.

This is overly simple metaphor; the brain isn’t made up of multi-colored, selectively bright light bulbs. Functional MRIs show blood flowing to an area of the brain, which is the best—though imperfect—way researchers have for showing brain activity. Scientists use “lit up” as a proxy for all this, but Lilienfeld and his coauthors argue that this gives laypeople the wrong idea that brain regions are actually illuminated when they’re working. They write:

Depending on the neurotransmitters released and the brain areas in which they are released, the regions that are “activated” in a brain scan may actually be being inhibited rather than excited (Satel and Lilienfeld, 2013). Hence, from a functional perspective, these areas may be being “lit down” rather than “lit up.”

“envy” vs. “jealousy”

In common usage, “envy” and “jealousy” are deployed interchangeably, but they are indeed distinct.

Envy is something you feel toward another person. It is a desire to be them or have what they have: physical attributes, money, success, that carefree joie de vivre. Jealousy is technically the fear of losing something through some kind of rivalry. Jealousy implies a relationship; if you are jealous, you feel the loss of your ex to his or her new partner, your relationship with your boss to your colleague, or your connection with your mother to your sibling. “Envy is a tango between two people, yet the dance of jealousy requires three,” therapist Esther Perel writes in her new book, The State of Affairs.

Psychologically, says Lilienfeld, there could be a basis for the difference. People who have narcissistic personality disorder, he says, tend to be envious of other people’s successes. They might find it difficult to feel happy for a coworker when he or she does well, for example. But they aren’t necessarily jealous people, says Lilienfeld; indeed narcissists tend to struggle with forming strong relationships with others.

“psychopathy” vs. “sociopathy”

“Psychopathy” is typically used to describe a personality disorder characterized by severe antisocial behavior, poor impulse control, lack of empathy, and unstable moods. “Sociopathy” is typically used to describe the same thing.

In fact, neither of these terms are formal psychological terms; the closest thing in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders is a category called “antisocial personality disorder.” Lilienfeld and his colleagues write that “sociopath” in particular is so ill-defined that they suggest it be retired.

“obsession” vs. “compulsion”

Obsessions and compulsions are very close in definition. Obsessions are repeated, unwanted thoughts and urges, while compulsions are repeated behaviors, urges, or thoughts that are a response to an obsession. A person might be obsessed with symmetry, and in response they might have a compulsion to ordering and reordering the items on their desk. “Obsessions are anxiety producing, whereas compulsions are anxiety reducing, at least in the short term,” write the researchers.

“mind-body therapies”

Listed in the oxymoron section of the paper, the term “mind-body therapies” is clearly held in disdain by the authors of the study. Labeling meditation, yoga, and Reiki as “mind-body therapies” implies that the mind and body are separate. In reality, most mainstream scientists would say there is no mind separate from the body; it’s a part of the body. “Rather than conceptualizing such interventions as making use of the mind to influence the body, we should conceptualize them as making use of one part of the body to influence another,” the researchers write.

“chemical imbalance”

The idea of a “chemical imbalance” implies there there’s such a thing as a chemical balance. According to the authors of the paper, an “imbalance” of neurotransmitters like serotonin and norepinephrine, associated with major depression, isn’t the right characterization, and even academics get it wrong, they say. “There is no known ‘optimal’ level of neurotransmitters in the brain, so it is unclear what would constitute an ‘imbalance,'” they write. “Nor is there evidence for an optimal ratio among different neurotransmitter levels.”