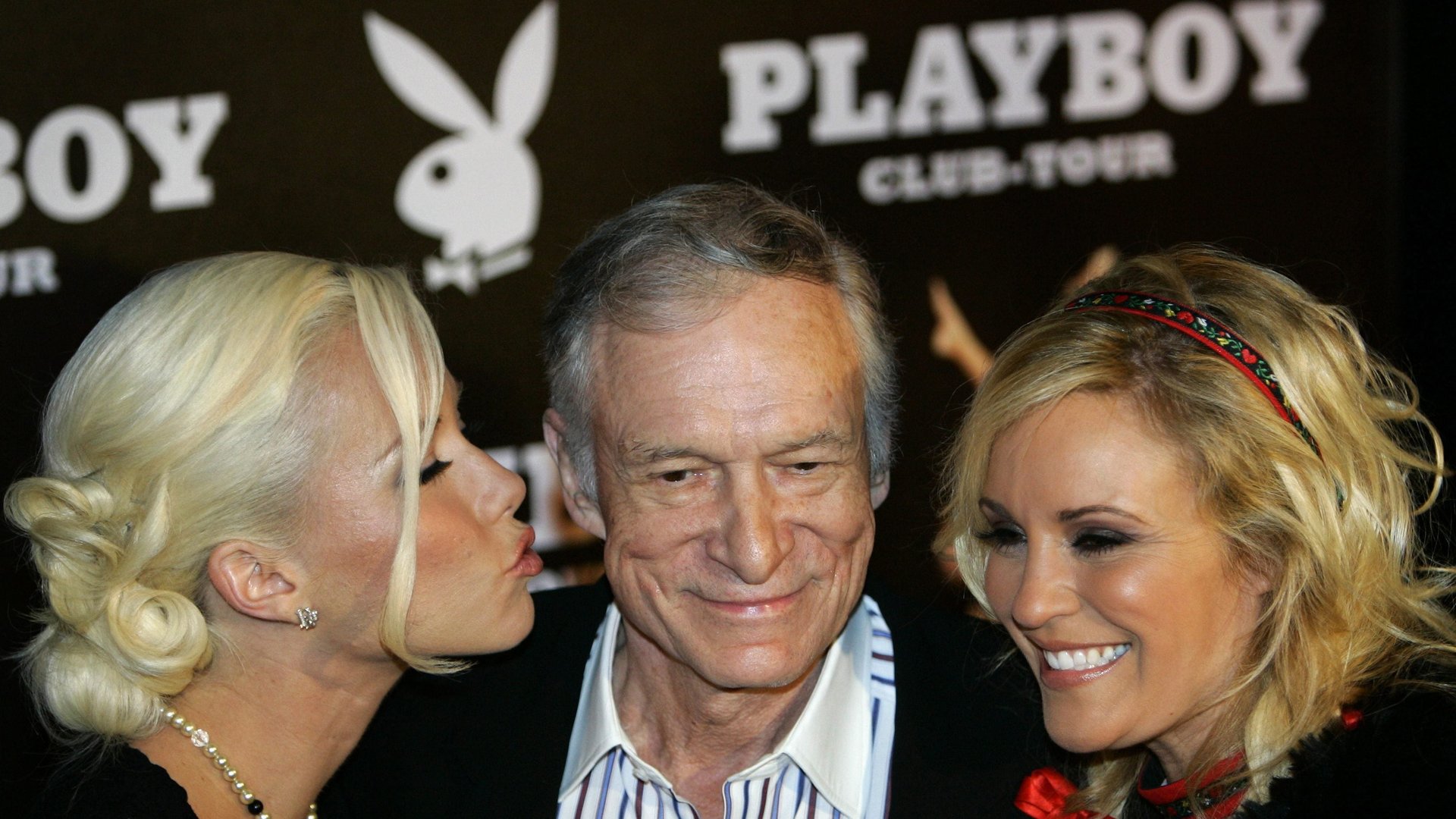

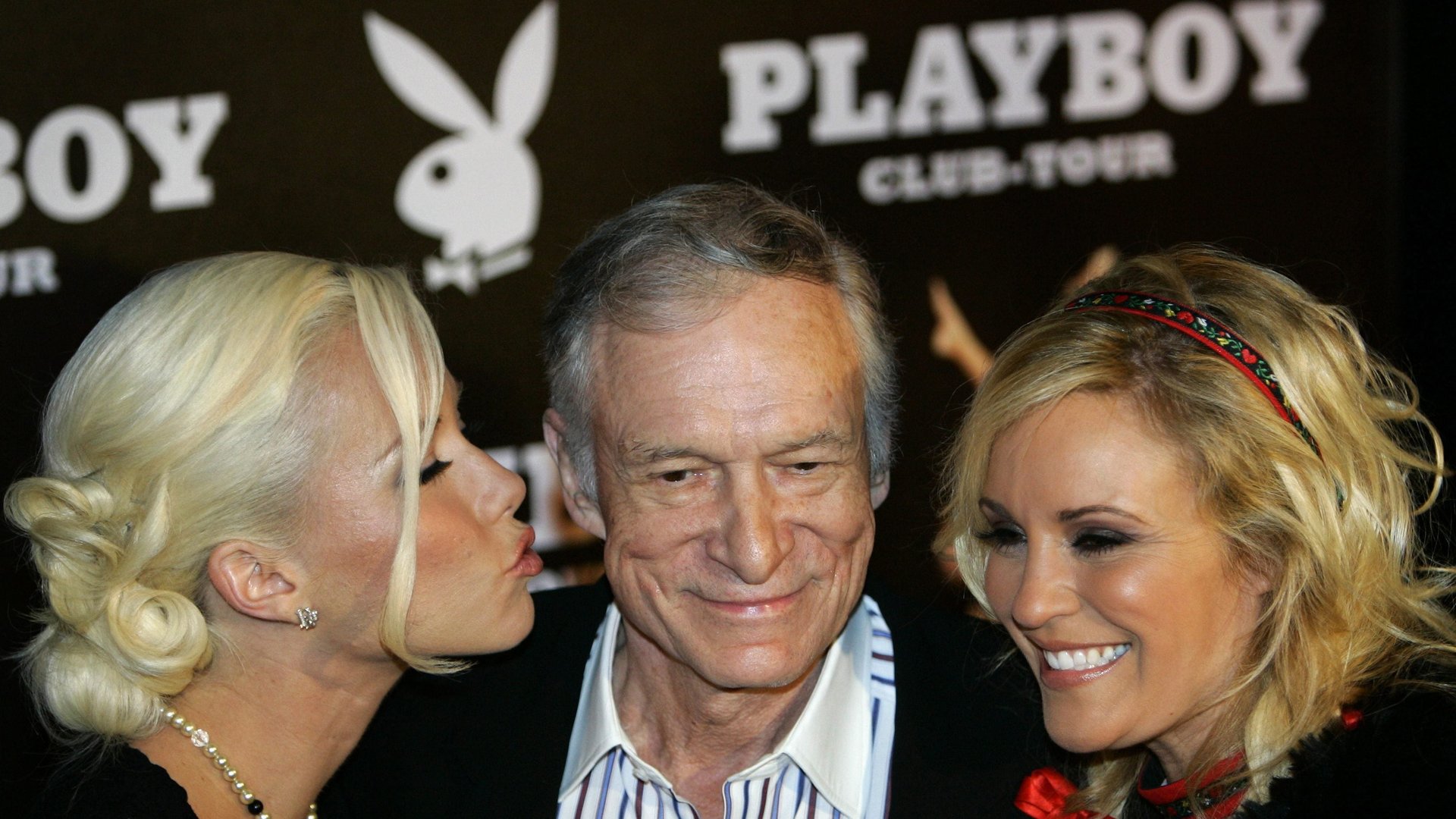

Remembering Playboy’s Hugh Hefner, the civil rights activist

Playboy Magazine founder Hugh Hefner, who died Wednesday (Sept. 27), will mostly be remembered for launching a publication that packaged pornography in a way that was broadly acceptable to the public. But Hefner’s legacy extends beyond pornography.

Playboy Magazine founder Hugh Hefner, who died Wednesday (Sept. 27), will mostly be remembered for launching a publication that packaged pornography in a way that was broadly acceptable to the public. But Hefner’s legacy extends beyond pornography.

The media magnate, who was 91, was an outspoken advocate for civil rights in the latter half of the 20th century.

Many of Hefner’s Playboy endeavors celebrated black contributions to American culture. In 1959, about six years after Playboy published its first issue, Hefner helped organize the Playboy Jazz Festival in Chicago, where black musicians including Dizzy Gillespie and Cannonball Adderly performed. Gross receipts for the festival’s first day went to the civil rights organization NAACP. Later editions of Playboy Jazz Festivals featured black and white musicians performing together on the same stage, at a time when Jim Crow segregation was still prevalent in the south.

An avid jazz fan, the very first Playboy interview published in the magazine was with Miles Davis. Interviewed by black journalist Alex Haley (who later wrote the book Roots), the piece focused not just on music, but on the relationship between Davis’s fame and his race.. The magazine later went on to publish interviews with Muhammad Ali, Martin Luther King Jr., and Malcolm X.

Hefner also launched and franchised out entertainment club venues bearing the Playboy brand, where black and white performers took the stage in front of mixed race audiences. When he discovered club owners were barring blacks from entry, he would buy back the franchise rights.

“Playboy was the first mainstream club, non-black club that actually put on stage black comedians,” Hefner told CBS in 2011. “Even in Las Vegas Black performers that performed on, including Sammy Davis, who was a very close friend of mine, would appear on stage, but they couldn’t walk through the casino. They had to walk through the back entrance.”

Hefner also used Playboy as a vehicle for promoting women’s reproductive rights—although many feminists objected to much of its subject matter as antithetical to that cause. The magazine came out in favor of abortion in 1965, and Hefner later established a nonprofit foundation that supported the Kinsey Institute (a nonprofit that researches sexual health), rape crisis centers, and the American Civil Liberties Union. A 1965 issue of Playboy featured a black playmate for the first time, possibly a “dubious distinction,” says the Root, but one that it notes came when the larger public culture rarely promoted black women as beautiful.

In 2013, he published an article declaring victory against the Republican party’s views toward sex.

“These are the final skirmishes of a retreating army of self-appointed moral authorities who have been defeated again and again for the past five decades,” he wrote. “Americans have rejected these religious fanatics and fought to protect women’s rights, reproductive rights and our right to privacy rather than submit to their Christian view that sex exists for the sole purpose of procreation.”

As the pornography industry moved online in the 2000s and magazine sales declined, Playboy lost much of its relevance. The company sold its television channel to online porn magnate Mindgeek (then known as Manwin) in 2011, and in 2015 it announced it would stop publishing nudes altogether. In 2016, Hefner put the company up for sale. At present, the company lives on as a men’s lifestyle blog in the West, and as a bunny-adorned apparel brand completely unrelated to sex in much of Asia.

But Hefner’s publication still shows its influence. Few contemporary media publications mix titillation with quality journalism like Playboy once did. But many mix seemingly lowbrow writing about sexuality with progressive politics. Hefner showed that media, even in the guise of a dirty magazine, could change the world.