Your next drug could be a pill full of genetically modified bacteria

The latest approach to making new drugs is genetically modifying members of our own microbial ecosystems.

The latest approach to making new drugs is genetically modifying members of our own microbial ecosystems.

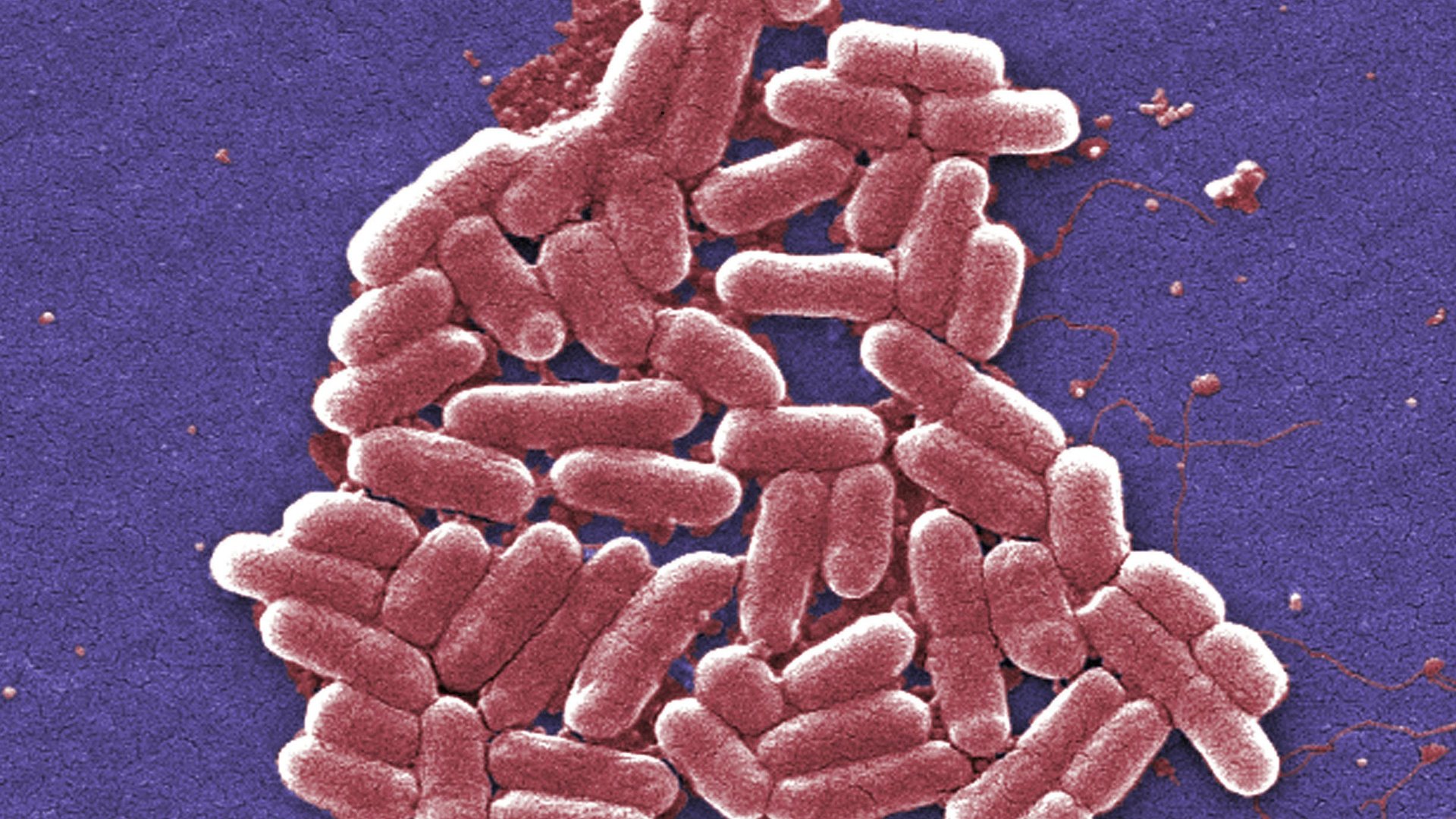

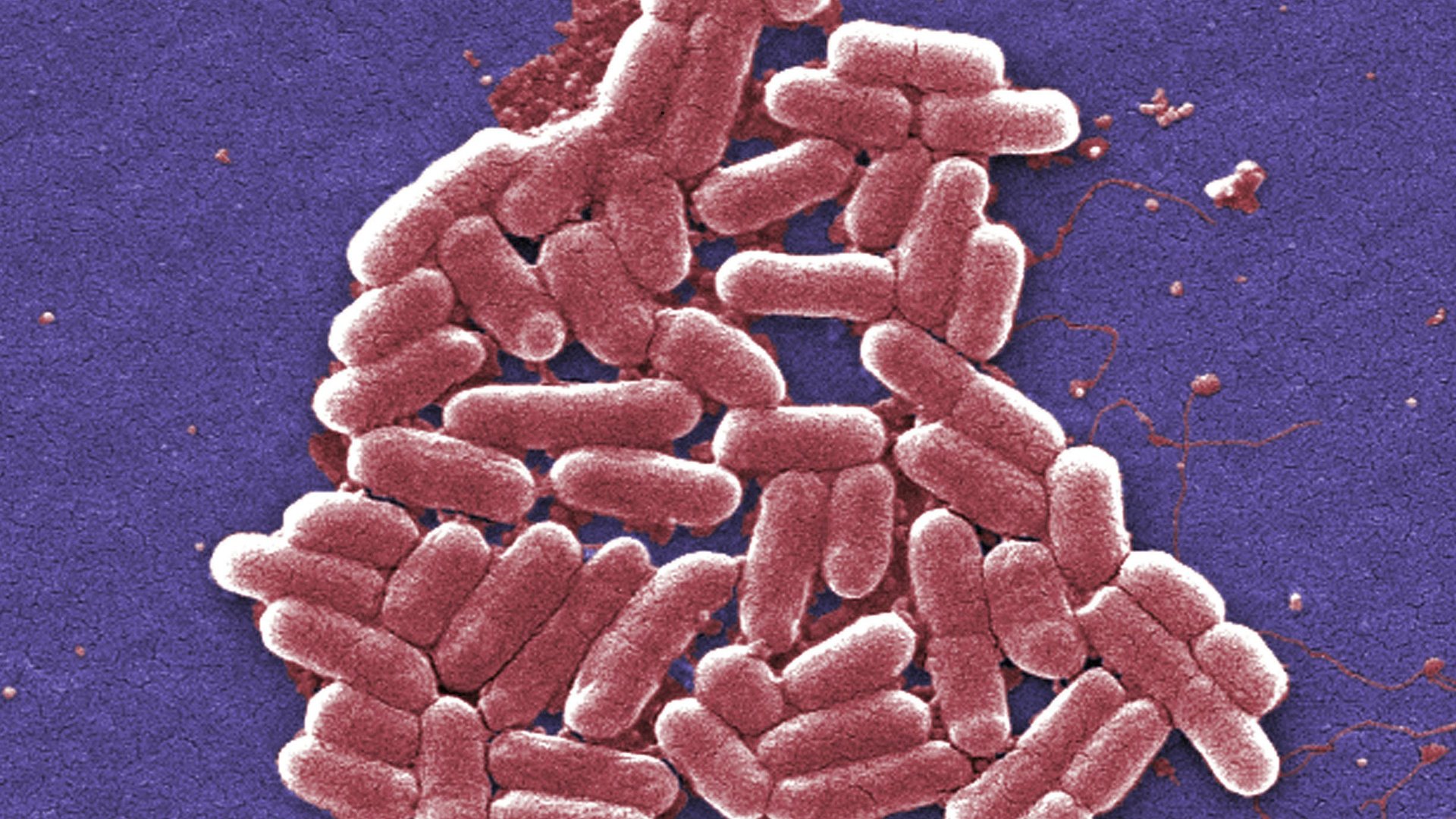

This summer, the Cambridge, Massachusetts-based biotech company Synlogic started a clinical trial studying the safety of pills filled with genetically modified Escherichia coli, the MIT Technology Review reports. These capsules are some of the first tries at generating “synthetic biotics” as a form of medicine. The US Food and Drug Administration thought these pills were so promising they fast-tracked them from animal to human testing.

In theory, they’d work like probiotics, which are foods or pills that help balance the trillions of bacteria that live in our digestive tract beneficially. Some of the bacteria in our mouths and colons, for example, process the food we eat to make vitamins. Others simply act like big barriers along our intestinal walls that use up all the food and space that would otherwise be occupied by harmful bacteria.

Along this line of thought, we could add custom bacteria strains that provide additional specific benefits. The strain of E. coli in Synlogic’s pills have been modified to get rid of the extra toxic ammonia that builds up in the body.

As your body goes about its business, it rids itself of waste that builds up over time, including ammonia. Normally, we’re able to excrete this chemical in our urine. However, a handful of rare genetic disorders prevent this from happening properly, and the concentration of extra ammonia must be managed through careful dieting. Even then, the condition can cause severe liver damage necessitating a transplant. If this first wave of synthetic biotics works, genetically modified E. coli could pick up the slack where the body’s machinery fails.

Typically, drug development is just as much luck as it is scientific inquiry. A lot of traditional drugs don’t even make it to testing in humans because while they make work in cell cultures, in animals trials they flop. If new drugs do seem to work in animals, there’s no guarantee that they’ll do the same in people. Compounds that are supposed to work in one part of the body may work in a totally different one. And even if these drugs work, researchers have to make sure that any harmful side effects are still worth the benefits.

E. coli is already a welcome guest in our guts. For the most part, these bacteria don’t cause a don’t harm us at all. It also happens to be one of the first species of bacteria scientists started genetically tinkering with. Back in 1978, California scientists edited E. coli to produce human insulin. Other companies are already working on genetically modified bacteria as drugs, too. Marina Biotech, a company in California, also announced this year that it would be testing bacteria-based therapies for two types of bowel disorders.

The Synlogic trial is in its early stages—it’s only being tested on healthy people to see if they can tolerate it. If this trial is successful, J.C. Gutierrez-Ramos, the CEO of Synlogic, told the MIT Technology Review he hopes to begin testing these modified E. coli in people with urea disorders some time next year.