New York’s ban on the illegal shark-fin trade won’t do much to protect sharks

Last Friday (July 26), New York state governor Andrew Cuomo signed a law banning the trade, consumption or possession of shark fins. New York’s not the first state; Maryland, California, Delaware, Illinois, Oregon, Washington and Hawaii have already enacted similar bans. And while a Texas recently bill failed, one is currently in the works in Massachusetts.

Last Friday (July 26), New York state governor Andrew Cuomo signed a law banning the trade, consumption or possession of shark fins. New York’s not the first state; Maryland, California, Delaware, Illinois, Oregon, Washington and Hawaii have already enacted similar bans. And while a Texas recently bill failed, one is currently in the works in Massachusetts.

All of these bans are aimed at protecting sharks from a grisly practice called “shark finning.” That’s where fishermen cut off and keep the shark’s valuable fin, chucking the wounded animal back in the sea to slowly bleed to death.

But shark finning is already illegal at a federal level in the US. So why the craze among state legislators to outlaw shark fins? The answer involves a ride through the complex and sometimes absurd world of US fishing regulations. And the sad conclusion is that because of those regulations, the state legislators’ efforts may come to naught. But first, some background…

Charismatic megafauna…

One reason for the lawmakers’ recent interest in finning: People love sharks. Sports teams and West Side Story gangs are named after them. Sure, they also fear them, thanks largely to the movie ”Jaws.” But it’s an admiring enough fear that the Discovery Channel now has a whole week of nonstop shark TV. They’ve even become cute—like Bruce, the vegetarian shark in Finding Nemo.

Along with sharks’ graduation into the “charismatic megafauna” class is the growing awareness that they’re endangered. About 29% of shark species face a high risk of extinction (pdf), while the populations of another 55% are threatened. That’s helped drum up popular support for those recent state bans.

…or tasty in soup?

In the Far East, though, instead of selling out movie theaters, sharks pack Chinese banquet halls—or their fins do, at least. These rubbery bits of flesh, the Chinese equivalent of caviar or foie gras, are used in a soup that goes for $100 a bowl.

The soup is thought to have medicinal properties. But above all, it signifies wealth. Fins of the fiercest sharks—hammerheads, tigers and great whites—tend to fetch the highest prices, which can be as high as $500 per pound. So the bigger and more menacing the soup’s fin, the more impressive the patron.

As China’s wealth has exploded in the last 15 years, demand for the showy soup has leapt off the charts. The result? Some shark populations have entirely collapsed. The number of great hammerheads, for instance, has fallen almost 80% within two to three generations.

Additionally, even though the big fins are used for presentation, those of smaller sharks are used to bulk up the soups. Here’s a look at some smaller fins for sale in New York’s Chinatown:

A drop in the shark-fin ocean

The New York ban means those jars will have to be emptied by next July, when the law takes effect. But the owner of Po Wing Hong Food Market, which is New York City’s second-largest supplier of fins to Chinese restaurants, says demand has already slumped in the last few years.

“There’s not much [demand] anymore. Only for some festivals and banquets,” Patrick Ng tells Quartz. “Now, because the image, it’s [seen as] not good. The new generation—they don’t like it.” Environmental awareness and the anticipation of the ban also seem to have played a part, he said.

More to the point, US demand for shark fins plays a pretty small role in the big picture. The vast majority of fins are consumed in East Asia. The global trade is between $400 million and $550 million each year (pdf, p.18).

Hong Kong, the main fin processing center, represents about half of that trade, and its suppliers are all over the planet:

The value in the fin

So it’s doubtful that a handful of American state bans will do much to dent the global fin trade. Rather, many lawmakers say, the bans will, by reducing US demand for fins, reduce fishermens’ incentive to carry out shark finning.

Shark fins fetch hundreds of times as much per pound as regular shark meat, but are only about 3%-5% of the shark’s total mass. “Finning” lets fishermen bring back 500 or so fins in a boat that would hold only 10-50 sharks. So at a rough calculation, a boatful of shark fins yields up to 30 times the value of the non-finning catch.

Finning is a pretty ugly practice. That’s one reason why the US federal government banned it in 2000, requiring fishermen to prove they caught the whole animal. They can still sell shark fins; they just can’t collect them by finning.

But since fishermen now must bring ashore the entire shark, it only makes sense to sell the meat. Hence a steady rise in shark meat exports as fishermen create new markets:

Shark meat by many other names

Now, people don’t seem to like the idea of eating sharks. But that doesn’t mean they aren’t doing so. The rock salmon that’s a favorite in UK fish and chips? Shark. France’s saumonette (“little salmon”)? Shark. The popular German bar-snack Schillerlocken (named after the hair of the poet, Friedrich Schiller)? Shark. And the list goes on—flake in Australia, palo rosado (“pink stick”) in Argentina, and sea-ham in Trinidad and Tobago.

Americans, though, are unusually squeamish about it. In the 1940s and 1950s, shark meat was sold as “steakfish,” “grayfish,” and “whitefish,” but current demand is so paltry that US lawmakers recently asked the agriculture department to buy surplus shark meat for school lunches.

So what happens to US fishermen who can’t sell shark fins anymore?

Though legislators haven’t come out and said it, the core objective of state bans is probably to discourage fishermen from catching sharks altogether. (After all, if you don’t catch sharks, you don’t catch shark fins.) This is because, even though demand for shark meat is growing, it’s still modest enough that profits mostly come from the fin. If fishermen can’t sell the fins, it’s probably not worth their while to sell shark meat on its own. “There aren’t really enough people [who want] to eat shark meat to [keep up with the number of people who] want the fins,” Patrick Kwan, director at the Humane Society, tells Quartz.

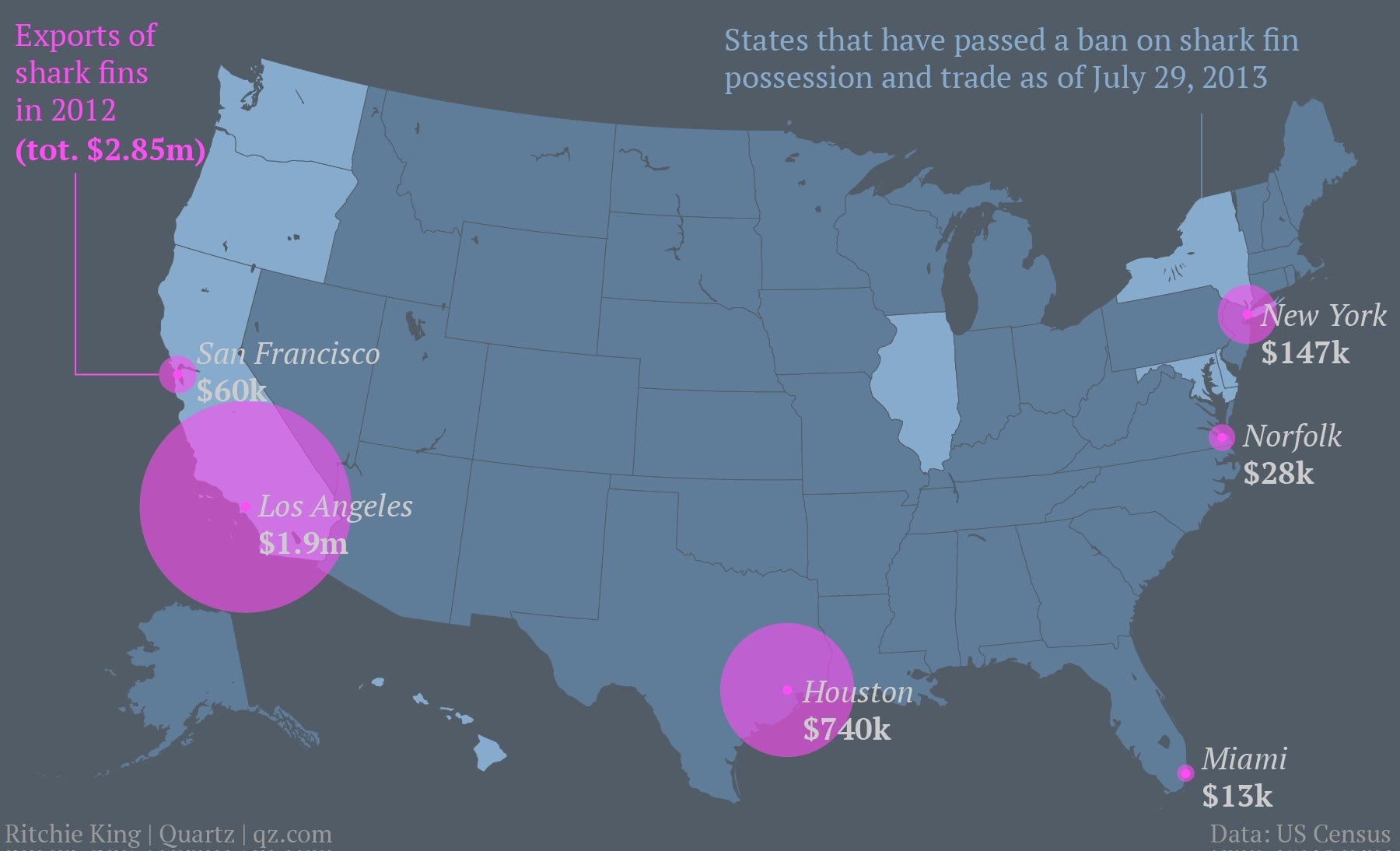

We’re about to find out whether that’s true. Not only will fishermen in states with bans be affected, but even those in states without bans will have a tough time, since New York and California are major centers of the export trade:

So on that score, the state bans on shark fins might seem like an effective way to really stamp out finning. Except for one little thing.

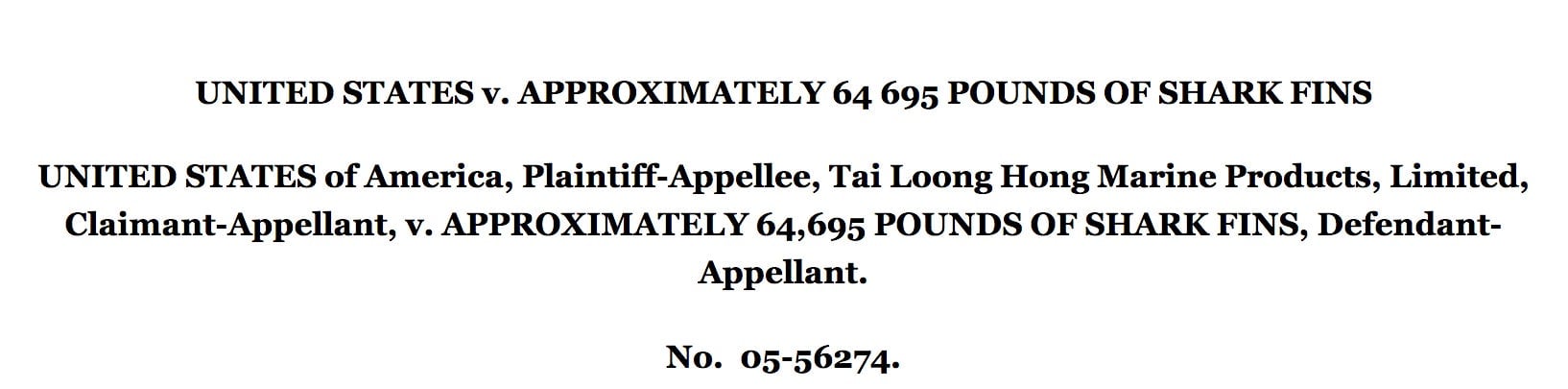

The upshot of United States v. Approximately 64,695 Pounds of Shark Fins

All the state bans on shark fins are undermined by a single loophole at the federal level. It all goes back to the 2000 Shark Finning Prohibition Act, and the complicated fishing bureaucracy that has sought to regulate finning.

The 2000 law instituted a 5% “fin-to-carcass ratio” for fishing boats. Fishermen couldn’t have any unattached shark fins on their boats weighing more than 5% of the total weight of shark carcasses on board. The fishermen could detach the fins from the carcasses—they’d do that because it makes it easier to store the carcasses and to prevent the fin meat from spoiling. But the idea was that, since sharks’ fins comprise up to 5% of their finless body weight, if your pile of fins exceeds that 5%, you’ve probably got some fins from sharks you threw back into the sea.

What the 2000 law messed up, though, is that it applied only to fishing vessels. In 2002, the government seized a US ship with 29.3 tons (32.3 tonnes) of shark fins, and not a single carcass. The government slapped a $600,000 fine on the captain and charterer. But since the ship in question wasn’t a fishing vessel, an appeals court overturned the fine, in what has to be one of the goofiest names for a court case in legal history, United States v. Approximately 64,695 Pounds of Shark Fins.

So in 2011 the US passed the Shark Conservation Act. This put the US at the international cutting edge of anti-finning legislation. Not only did Congress expand the law to non-fishing vessels, it also did away with fin-to-carcass ratios altogether. Instead, it required that sharks be brought back to land with their fins attached—the so-called “fins on” rule.

This was the game-changer. In theory, it would now be impossible for US fishermen to engage in finning. Except that the 2011 law made one little exception: for a shark species known as the smooth dogfish.

Pity the dogfish

People might love sharks. But they don’t love dogfish. Why? First of all, they’re ugly:

Its Latin name nails it: Mustelus canis, or ”weaselly dog.” Rather than the fear-inspiring “lifeless black” eyes of their charismatic cousins, dogfish eyes are a feral yellow. Because the females are much bigger than the males, and they rove the Atlantic in packs, they have more of a tween girl-gangs-of-the-sea reputation than the lone-predator image of other species.

They don’t even have razor-like teeth. Instead, smooth dogfish have boring rows of molars. If ever anyone were to make a movie about a dogfish gone rogue, it wouldn’t be called “Jaws”; it would probably be “Overbite”.

The 2011 Shark Conservation Act tightened up the rules for the killing of all other sharks. But for smooth dogfish it not only allowed fishermen to keep cutting fins off the sharks as long as they maintained a fin-to-carcass ratio; it upped the ratio to 12%, which is likely to go into effect very soon.

That’s a strange discrepancy, given that dogfish fins weigh only around 3% of their carcass. Hmmm. Why could that be?

The exception that lets fishermen stay afloat…

It’s not just the federal law that carves out dogfish. New York’s shark fin ban excludes the smooth dogfish too—and so do Maryland’s and Delaware’s. That means you can still have shark fin soup in New York—as long as it’s the fin of a smooth dogfish.

On the face of it this just seems like a way to protect fishermen from bankruptcy. Since smooth dogfish fins can comprise about 40% of their total profits, fishermen can at least protect some of their margins. Smooth dogfish (as well as spiny dogfish, the other shark excepted in the state bans) offer a crucial revenue source, as Greg Walinski, a Massachusetts fisherman, explained to the Boston Globe. ”If we can’t sell the fins, we’d be done—there is such a fine margin to make money on dogfish.”

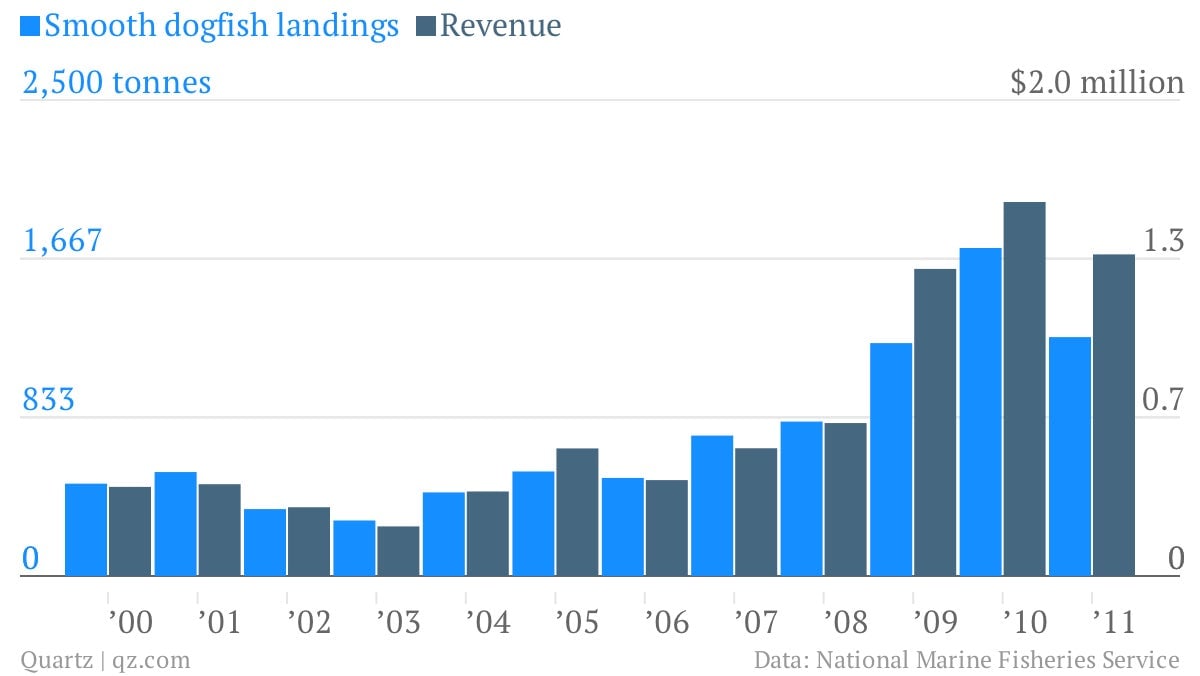

However, unlike with almost all other sharks, no one has ever measured the smooth dogfish population or how rampant fishing will affect it. They’re already being fished a lot more than they were:

And the recent legal changes mean that’s likely to increase further.

…but offers law-breakers a loophole…

And there’s a more serious problem, which is that making an exception for dogfish finning may open the door to a whole lot of illegal finning of other sharks. Sonja Fordham, president of Shark Advocates International, says that because the fins of various shark species are notoriously hard to tell apart, “There will be a whole lot more wiggle room for undetected finning” of sharks whose fins can pass for smooth dogfish fins. And with that oddly high 12% fin-to-carcass ratio for dogfish, fishermen will be tempted to pile up fins—of smooth dogfish and anything else they catch—until they hit the legal weight limit.

In fact, that 12% quota is almost an invitation to illegal finners to keep finning.

“The [fin-to-carcass] ratio provides an opportunity to harvest extra fins from more sharks,” said Leah Biery, lead researcher on a recent study about shark management. ”It does not prevent waste or overfishing, as the law intended.” Fordham is even more damning: the net effect of these conservation policies, she says, is to ”make the rules against shark finning more lenient.”

…and encourages other countries to keep finning

Beyond the cruelty of shark-finning, the fin trade also contributes to shark overfishing. Lawmakers and regulators alike still have only a flimsy understanding of how many sharks are left, says Dr. Shelley Clarke, one of the world’s foremost experts on the shark fin trade. “Scientists attempting to assess stock status are still faced with major data gaps regarding the number and rate at which sharks are historically and currently being taken,” Clarke tells Quartz. “There are some, but not many, countries which regulate how many sharks can be caught, but for most fisheries there are no limits on catches.”

Scientists and conservationists largely agree that the “fins on” approach—requiring sharks to be brought back to land with their fins attached—is the only way to prevent shark-finning. In countries with big fishing industries, it can be tough to pass such laws. The European Union, which once supplied around one-third of the world’s fins, only passed a “fins on” law earlier this year.

This means the EU can now take the lead urging other countries to adopt similar bans. By contrast, the dogfish loophole in the US’s law weakens the country’s moral authority, says SAI’s Fordham.

“The US is going in the absolutely the wrong direction at the time when governments are moving toward stronger enforcement,” she says. “It really is a case where the short-term economic wishes of a handful of US states can undermine finning regulations around the word.”

Update: For the sake of accuracy, this post’s headline has been updated from the original, which read “New York’s ban on the illegal shark-fin trade may do nothing to protect sharks.” The first and second paragraphs have also been changed to clarify that the bans aim to protect sharks by prohibiting the consumption of shark fins, in addition to possession and sale.