Despite the hype, nobody is beating Nvidia in AI

You have to wonder whether Nvidia is going to get sick of winning all the time.

You have to wonder whether Nvidia is going to get sick of winning all the time.

The company’s stock price is up to $178—69% more than this time last year. Nvidia is riding high on its core technology, the graphics processing unit used in the machine-learning that powers the algorithms of Facebook and Google; partnerships with nearly every company keen on building self-driving cars; and freshly announced hardware deals with three of China’s biggest internet companies. Investors say this isn’t even the top for Nvidia: William Stein at SunTrust Robinson Humphrey predicts Nvidia’s revenue from selling server-grade GPUs to internet companies, which doubled last year, will continue to increase 61% annually until 2020.

Nvidia will likely see competition in the near future. At least 15 public companies and startups are looking to capture the market for a “second wave” of AI chips, which promise faster performance with decreased energy consumption, according to James Wang of investment firm ARK. Nvidia’s GPUs were originally developed to speed up graphics for gaming; the company then pivoted to machine learning. Competitors’ chips, however, are being custom-built for the purpose.

The most well-known of these next-generation chips is Google’s Tensor Processing Unit (TPU), which the company claims is 15-30 times faster than others’ central processing units (CPUs) and GPUs. Google explicitly mentioned performance improvements over Nvidia’s tech; Nvidia says the underlying tests were conducted on Nvidia’s old hardware. Either way, Google is now offering customers the option to rent use of TPUs through its cloud.

Intel, the CPU maker recently on a shopping spree for AI hardware startups—it bought Nervana Systems in 2016 and Mobileye in March 2017—also poses a threat. The company says it will release a new set of chips called Lake Crest later in 2017 specifically focused on AI, incorporating the technology it acquired through Nervana Systems. Intel is also hedging its bets by investing in neuromorphic computing, which uses chips that don’t rely on traditional microprocessor architecture but instead try to mimic neurons in the brain.

ARK predicts Nvidia will keep its technology ahead of the competition. Even disregarding the market advantage of capturing a strong initial customer base, Wang notes that the company is also continuing to increase the efficiency of GPU architecture at a rate fast enough to be competitive with new challengers. Nvidia has improved the efficiency of its GPU chips about 10x over the past four years.

Nvidia has also been investing since the mid-aughts in research to optimize how machine-learning frameworks, the software used to build AI programs, interact with the hardware, critical to ensuring efficiency. It currently supports every major machine-learning framework; Intel supports four, AMD supports two, Qualcomm supports two, and Google supports only Google’s.

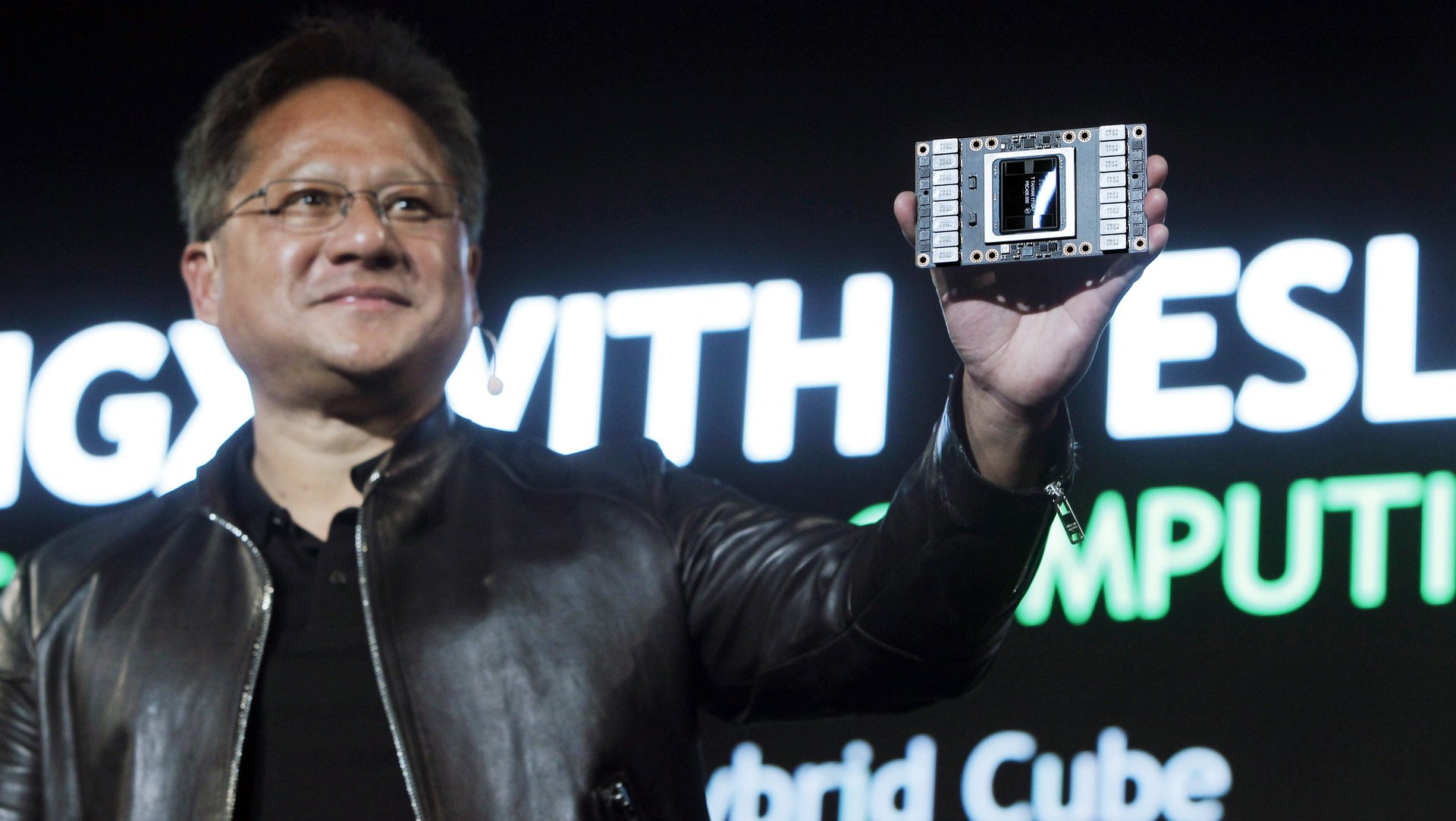

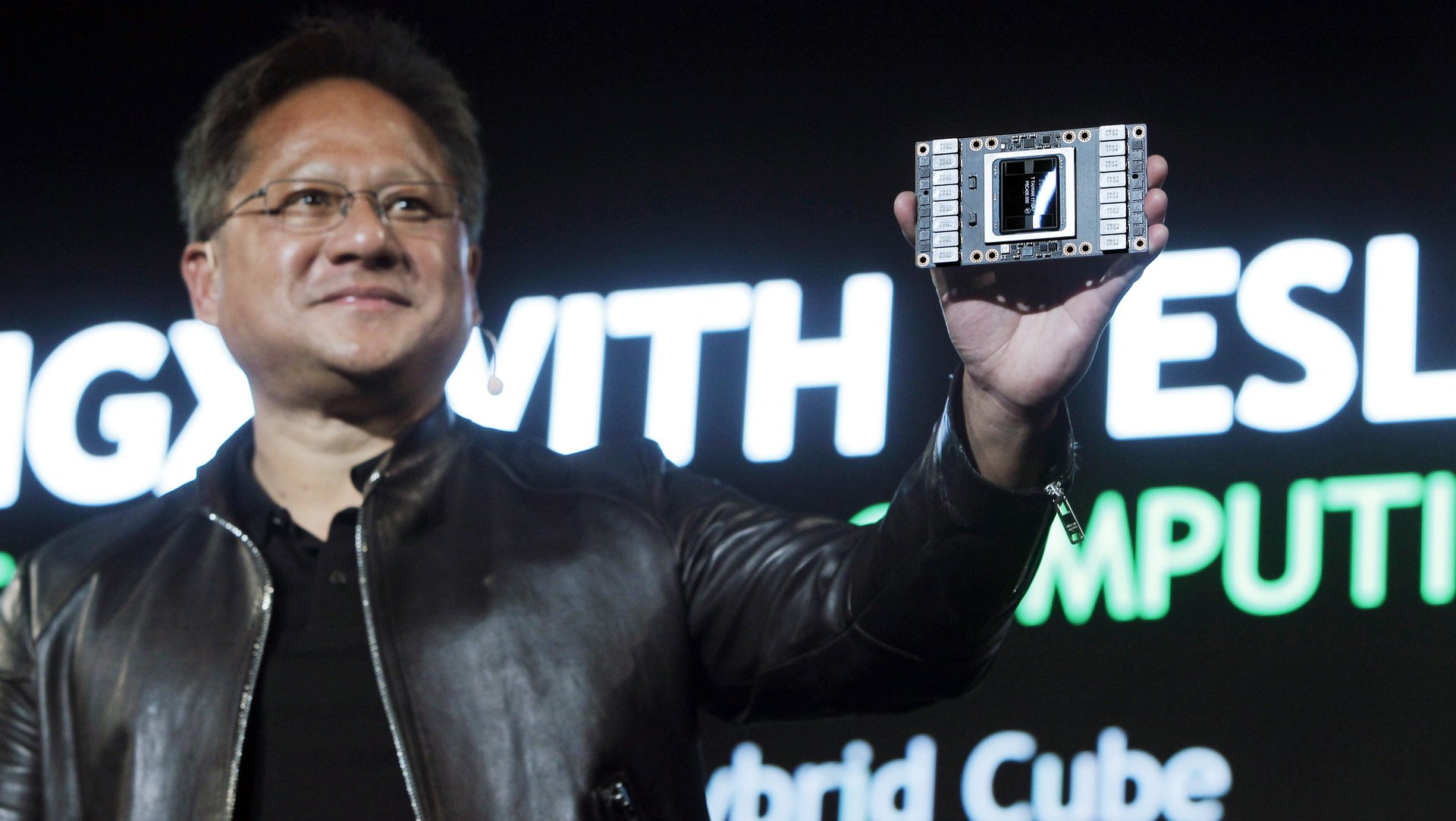

Since GPUs aren’t specifically built for machine learning, they can also pull double-duty in a datacenter as video- or image-processing hardware. TPUs are custom-built for AI only, which means they’re inefficient at tasks like transcoding video into different qualities or formats. Nvidia CEO Jen-Hsun Huang told investors in August that “a GPU is basically a TPU that does a lot more,” since many social networks are promoting video on their platforms.

“Until TPUs demonstrate an unambiguous lead over GPUs in independent tests, Nvidia should continue to dominate the deep-learning data center.” Wang writes, noting that AI chips for smaller devices outside of the datacenter are still ripe for startups to disrupt.