Humans had to evolve to acknowledge octopus consciousness

Octopuses are popular these days, the subjects of numerous scientific studies and books in which humans acknowledge their intelligence, consciousness, and potential to shed light on our own lives. The shape-shifting, eight-tentacled sea creatures even have their own dedicated World Octopus Day every Oct. 8.

Octopuses are popular these days, the subjects of numerous scientific studies and books in which humans acknowledge their intelligence, consciousness, and potential to shed light on our own lives. The shape-shifting, eight-tentacled sea creatures even have their own dedicated World Octopus Day every Oct. 8.

It wasn’t always this way. Historically, people feared and loathed these intelligent invertebrates we’re now coming to respect.

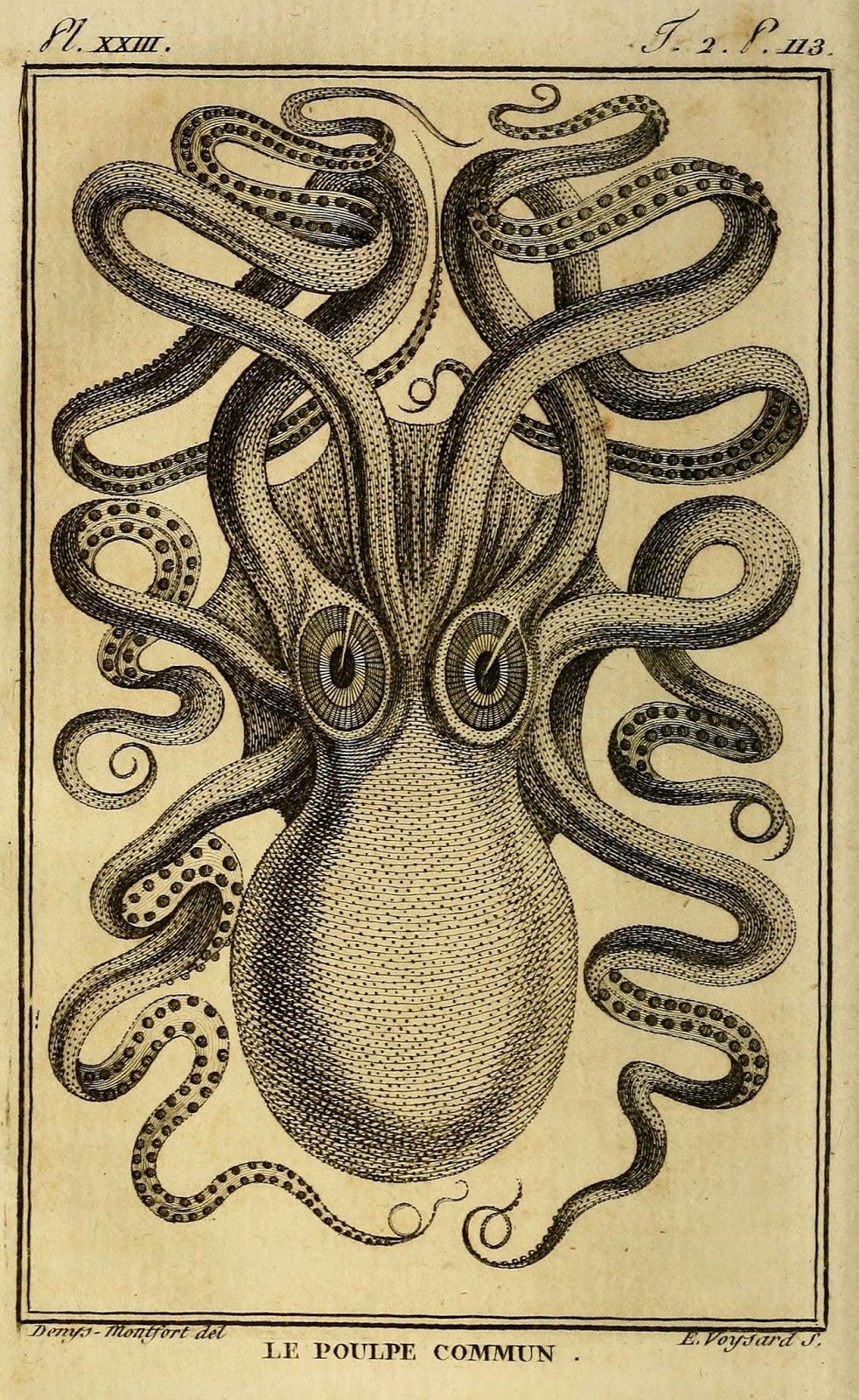

Octopus fear dates back to the Roman Empire, at least. “No animal is more savage in causing the death of man in the water, for it struggles with him by coiling round him and it swallows him with sucker-cups and drags him asunder,” wrote Pliny the Elder in Naturalis Historia in 79 AD. This early account set the negative tone for our views of cephalopods for centuries. For example, Pierre Denys de Montfort wrote in 1801 in Histoire Naturelle Générale et Particulière des Mollusques of a vicious octopus attack at the beach—an account later dismissed as unreliable—and provided an illustration of a creepy creature resembling the Kraken, a legendary Norse sea monster that is believed to be based on the giant squid.

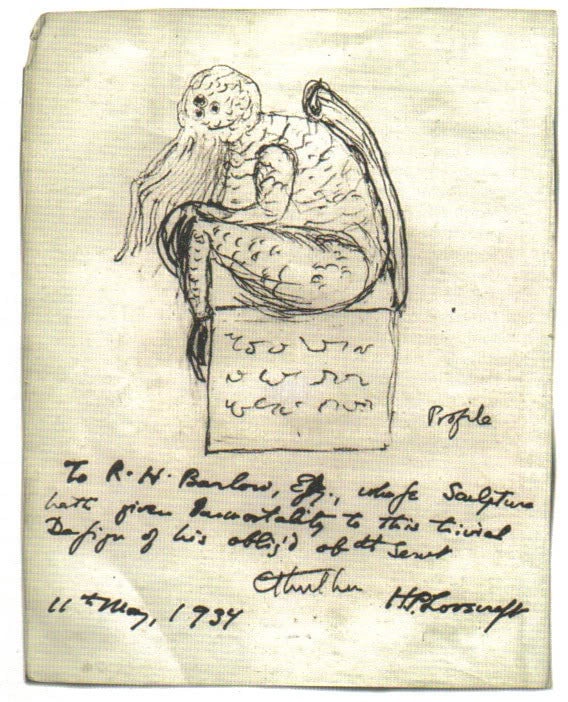

The bad buzz for cephalopods culminated in the creation in 1926 of possibly the most famous and horrible octopus-inspired literary sea creature ever, Cthulhu. Classic horror writer HP Lovecraft’s Cthulhu was a “monster of vaguely anthropoid outline, but with an octopus-like head whose face was a mass of feelers, a scaly, rubbery-looking body, prodigious claws on hind and fore feet, and long, narrow wings behind.”

This description, from the short story “The Call of Cthulhu,” obviously doesn’t sound like an octopus. But it captures much of what had, in the past, made humans so uncomfortable about the creatures. “An octopus is as different from a person physically as creatures can get,” naturalist Sy Montgomery, author of the 2015 book The Soul of an Octopus, told Quartz. ”They have no bones, three hearts, blue blood, a beak like a parrot, venom like a snakes. They can pour their baggy bodies through small openings; they can change color and shape; they can taste with their skin.”

The evolution of humans

Alienness seemed likely to doom the octopus forever. “Their strangely repulsive appearance, and the fictional stories of their attacks, have built up in the popular mind a picture of the ‘devil fish’ which no amount of accurate description is ever likely to cut down to authentic size,” predicted Frank W. Lane in the 1962 book, Kingdom of the Octopus.

Lane was overly pessimistic, however. We’ve evolved when it comes to cephalopods; the strangeness that once repulsed us is now a source of fascination, seen as a sign that they have much to reveal. Montgomery, for example, experienced meeting an octopus with none of the revulsion of naturalists of the past, and told Quartz that since her first such meeting she’s “had the great privilege of knowing several octopuses well enough to consider them close friends.” In her book, she writes of her initial encounter with a creature named Athena:

Athena’s suction is gentle, though insistent. It pulls me like an alien’s kiss. Her melon-sized head bobs to the surface, and her left eye—octopuses have a dominant eye, as people have dominant hands—swivels in its socket to meet mine. Her black pupil is a fat hyphen in a pearly globe. Its expression reminds me of the look in the eyes of paintings of Hindu gods and goddesses—serene, all-knowing, heavy with wisdom stretching back beyond time.

Montgomery’s sense that octopuses had a timeless quality is well-founded. Diver, philosopher, and octopus researcher Peter Godfrey-Smith, of the City University of New York, explored octopus consciousness in his recent book Other Minds. He posits that octopuses evolved before humans—there is evidence to suggest that they have been on Earth 1,000 times longer than us. It’s as if, he writes, evolution created (at least) two versions of the mind. Although mammals (humans especially) and birds, were once believed the most intelligent beings, Godfrey-Smith suggests we may have failed to recognize cephalopod IQ because it looks so different than ours.

We also didn’t used to have as much access to octopuses. Familiarity seems to be breeding respect rather than contempt when it comes to our relationship with cephalopods. New technology has allowed divers and scientists to observe cephalopods in their natural environments and in labs. They’ve discovered that octopus behavior indicates profound complexity. Octopus minds extend beyond the brain, for example. Each of an octopus’s eight arms has firing neurons, and seems to have a mind of its own; an octopus’s tentacles remain responsive to stimuli even after being severed from the rest of its body.

We also now know that individual octopuses behave differently and have a cephalopod version of a personality; communicate with each other and with researchers; can recognize individual people and respond to them differently; and can engineer small cities.

Recognizing intelligence

Marine biologist David Scheel of Alaska Pacific University recently published a study announcing the discovery of Octlantis, in Jervis Bay, Australia. It’s the second “octopus city” we humans have discovered, following one unearthed nearby, a few years back, by Godfrey-Smith.

Scheel has been studying octopuses since 1995 and has come to see them as kind of reflection on humanity, illuminating behaviors we may take for granted. Take blushing, for example. People might not consider blushing, from embarrassment, say, to be a complex behavior. But when the marine biologist observes octopuses undergoing color changes, it causes him to reconsider the meaning of human color changes caused by emotion. As he explained to KTUU Anchorage, “They’re also complex animals with fascinating behaviors and so by studying them we can come to better understand how we got to be complex animals with our own fascinating behaviors.”

Scheel is now working with two octopuses on campus, dubbed Darwin and Sprite, to learn more about how their behaviors—which, he thinks, will in turn teach him more about cephalopod and human behavior.

According to animal behaviorist Jessie Peissig at California State University in Fullerton, studying octopuses could also help us to build smarter machines. Peissig is about to embark on an octopus study that will examine how the squishy invertebrates learn and retain information. “We’re interested in systematically testing learning and memory in the octopus, so we can make direct comparisons to vertebrates,” she said in a statement about her upcoming work. “Similarities will tell us about constraints within biological systems, and differences could lead us to discover alternative processing strategies. These alternative processing strategies could be important for other fields of research, such as artificial intelligence.”

Peissig is one of many academics in a range of fields—including marine biology, philosophy, psychology, and cognition—studying cephalopods to better understand intelligence generally. It’s taken centuries for us to reach this point, but it seems we’ve made it at last. Humans are finally smart enough to recognize intelligence in our elders.