Shinzo Abe’s electoral rival Yuriko Koike is vowing to take down one of Japan’s greatest evils—hay fever

Millions of Japanese people develop runny noses and watery eyes every spring—so a promise by Tokyo governor Yuriko Koike, whose party wants to dethrone prime minister Shinzo Abe, to do something about pollen might just pique their interest.

Millions of Japanese people develop runny noses and watery eyes every spring—so a promise by Tokyo governor Yuriko Koike, whose party wants to dethrone prime minister Shinzo Abe, to do something about pollen might just pique their interest.

Laying out its manifesto today (Oct. 6), Koike’s newly formed Party of Hope unveiled a list of “12 zeroes” (link in Japanese), pledging to eliminate, among other things, passive smoking, nuclear power, waiting lists for child care, and hay fever. The Party of Hope, which will face Abe’s Liberal Democratic Party on Oct. 22, also announced a number of economic initiatives dubbed as “Yurinomics,” an answer to Abe’s “Abenomics” campaign.

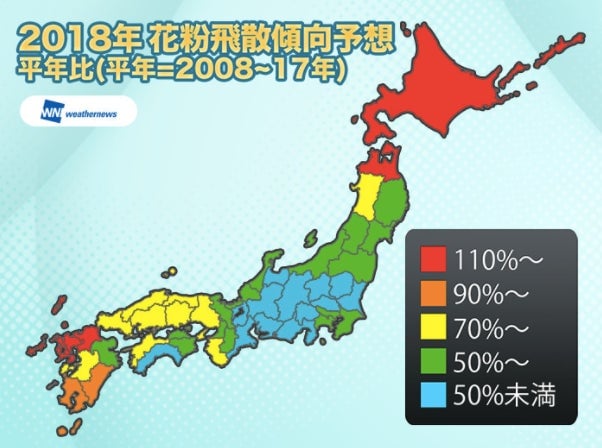

Hay fever is a serious enemy for many people in Japan. Just as they closely watch the dates for the unfolding of cherry blossoms and autumn foliage across Japan every year, Japanese people also follow government advisories (link in Japanese) showing pollen levels in the country when spring rolls around. During the season, Japanese department stores also display products for hay-fever victims, including face masks and glasses. By one estimate, about a quarter of Japanese people suffer pollen allergies.

The two main culprits of hay fever in Japan are pollen from the sugi and hinoki cypress trees. The sugi, or Japanese redwood, is the national tree of Japan, while hinoki trees are typically used for the construction of shrines.

Japan’s pollen problem is its own making. As part of the post-war effort to rebuild its economy, the country planted millions of cypress trees for their lumber to replace the swathes of forests that were destroyed during World War II. As cheaper timber imports started to flood into the country, the mature, domestic trees were left alone, massively increasing pollen levels in Japan. Pollen allergies in Japan started becoming more common in the 1960s.

In response, Japanese forestry researchers have been trying to develop pollen-free trees with some success, but the speed and quantity is unlikely to be able to make up for the millions of pollen-bearing cedar trees that remain unfelled, particularly as the demand for wood for construction decreases.

Koike isn’t the first to pledge to rid Japan of pollen. Former Tokyo governor Shintaro Ishihara, himself a sufferer of hay fever, made a similar pledge in 2005. As a result of Ishihara’s angry tirade against hay fever, the education ministry at the time encouraged the construction of schools and other buildings with wood to speed up the use of pollen-emitting trees.

In 2006, Ishihara proposed cutting over 1.8 million trees in 10 years in forests west of Tokyo, but the plan is behind schedule. By one estimate (link in Japanese), only 1.6% of the trees in the area have been replaced by lower-pollen varieties. At that pace, it would take some 600 years to get rid of pollen-emitting trees. In the face of the force of nature, Koike may have better luck at taking something else to zero.