Germany has way more industrial robots than the US, but they haven’t caused job losses

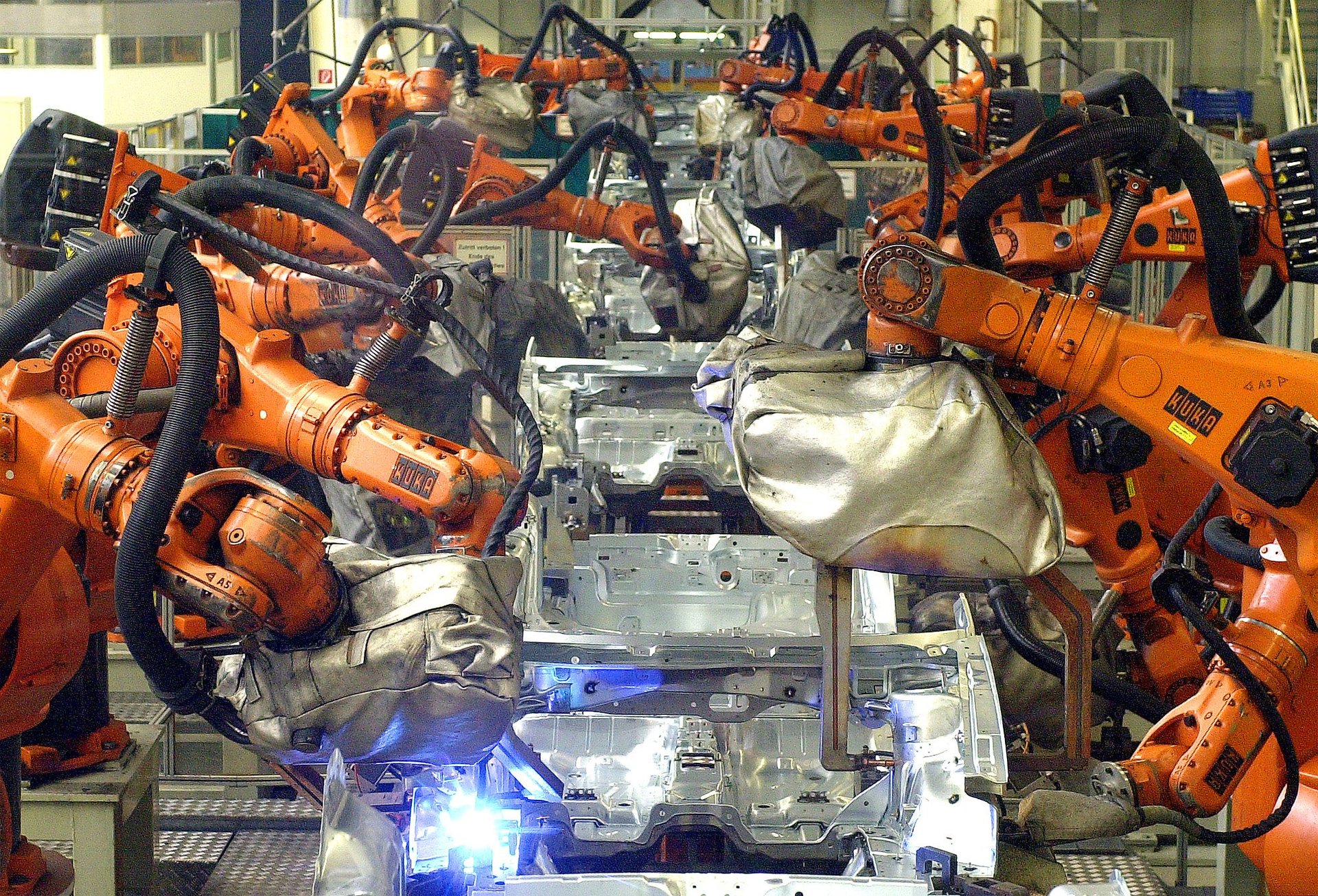

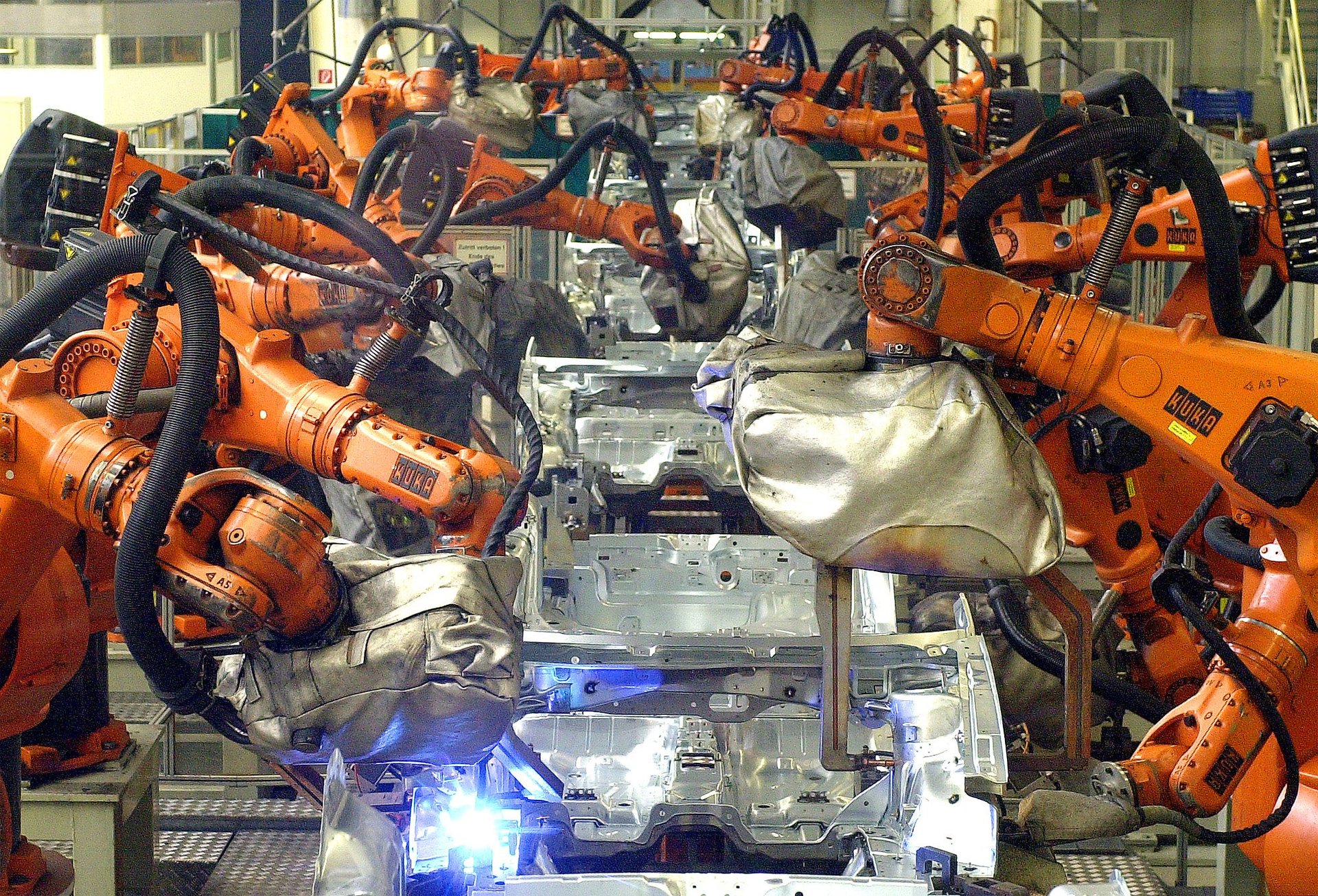

The rise of the robots, coming first for our jobs, then maybe our lives, is a growing concern in today’s increasingly automated world. Just today (Oct. 10), the World Bank chief said the world is on a “crash course” to automate millions of jobs. But a recent report from Germany paints a less dramatic picture: Europe’s strongest economy and manufacturing powerhouse has quadrupled the amount of industrial robots it has installed in the last 20 years, without causing human redundancies.

The rise of the robots, coming first for our jobs, then maybe our lives, is a growing concern in today’s increasingly automated world. Just today (Oct. 10), the World Bank chief said the world is on a “crash course” to automate millions of jobs. But a recent report from Germany paints a less dramatic picture: Europe’s strongest economy and manufacturing powerhouse has quadrupled the amount of industrial robots it has installed in the last 20 years, without causing human redundancies.

In 1994, Germany installed almost two industrial robots per thousand workers, four times as many as in the US. By 2014, there were 7.6 robots per thousand German workers, compared to 1.6 in the US. In the country’s thriving auto industry, 60–100 additional robots were installed per thousand workers in 2014, compared to 1994.

Researchers from the Universities of Würzburg, Mannheim, and the Düsseldorf Heinrich-Heine University examined 20 years of employment data to figure out how much of an effect the growth of industrial manufacturing has had on the German labor market.

They found that despite the significant growth in the use of robots, they hadn’t made any dent in aggregate German employment. “Once industry structures and demographics are taken into account, we find effects close to zero,” the researchers said in the report.

Robots are changing career dynamics

While industrial robots haven’t reduced the total number of jobs in the German economy, the study found that on average one robot replaces two manufacturing jobs. Between 1994 and 2014, roughly 275,000 full-time manufacturing jobs were not created because of robots.

“It’s not like jobs were destroyed, in the sense that a manufacturing robot is installed and then the workers are fired because of the robots—that never really happened in Germany,” study co-author Jens Südekum, from Düsseldorf Institute for Competition Economics, told Quartz. “What happened instead is that in industries where they had more robots, they just created fewer jobs for entrants.”

“Typically around 25% of young labor market workers went into manufacturing and the rest did something else, and now more workers have immediately started in the service sector—so in a sense the robots blocked the entry into manufacturing jobs.”

The study also found that those who are already in jobs where they were more exposed to automation, were significantly more likely to keep their jobs, though some ended up doing different roles from before. The big downside for some medium-skilled workers, who did manual, routine work, was that it meant taking pay cuts.

“This is where these wage results come in, what we find is that no one was really fired because of a robot, but many swallowed wage cuts. And this has mostly affected medium-skilled workers who did manual routine tasks.” Around 75% of manufacturing workers are medium skilled, and the wage cuts have so far been moderate, he says.

But Germany hasn’t got it perfect. One core reason for why Germans haven’t been fired in favor of robot, is the country’s famously powerful unions and work councils, which have are often keen to accept flexible wages on behalf of workers, to maintain high employment levels.

“Unions of course have a very strong say in wage setting in Germany,” Südekum says. “It’s known that they are more willing than unions in other countries to accept wage cuts to ensure jobs are secured.”

While robots have increased productivity and profits, and not driven people into unemployment (yet), they haven’t been good news for blue collar workers in Germany.

“The robots really fueled inequality, because they benefitted the wages of highly skilled people—like managers and scientists, people with university education—they even gained higher wages because of the robots, but the bulk of medium-skilled production workers suffered.”