After a twenty-year trade embargo, the United States has lifted sanctions against the government of Sudan. It follows bilateral agreements to cede hostilities in key regions, expand humanitarian access to those affected, and collaborate to address the threat of terrorism.

The revocation, which takes effect on Oct. 12, signals the dawn of new relations between the two countries who have had a checkered diplomatic history since the sanctions were first imposed in 1997.

The Trump administration said the decision came after a 16-month effort that showed Sudan was “serious” about promoting regional stability. The State Department noted the Sudanese government had stopped its attacks on areas including Darfur and South Kordofan and was helping the US deal with the threat of the Lord’s Resistance Army, a relentless cult that has been waging war in northern Uganda for decades. The move to ease the sanctions comes barely two weeks after Sudan was removed from the list of countries whose citizens were banned from traveling to the United States.

For two decades, the comprehensive US sanctions crippled the Sudanese economy, increasing debt and inflation, and paralyzing the banking sector. After the secession of South Sudan in 2011, the government lost over half of its revenues that came from the oil industry, increasing fuel prices and leading to violent protests in 2013.

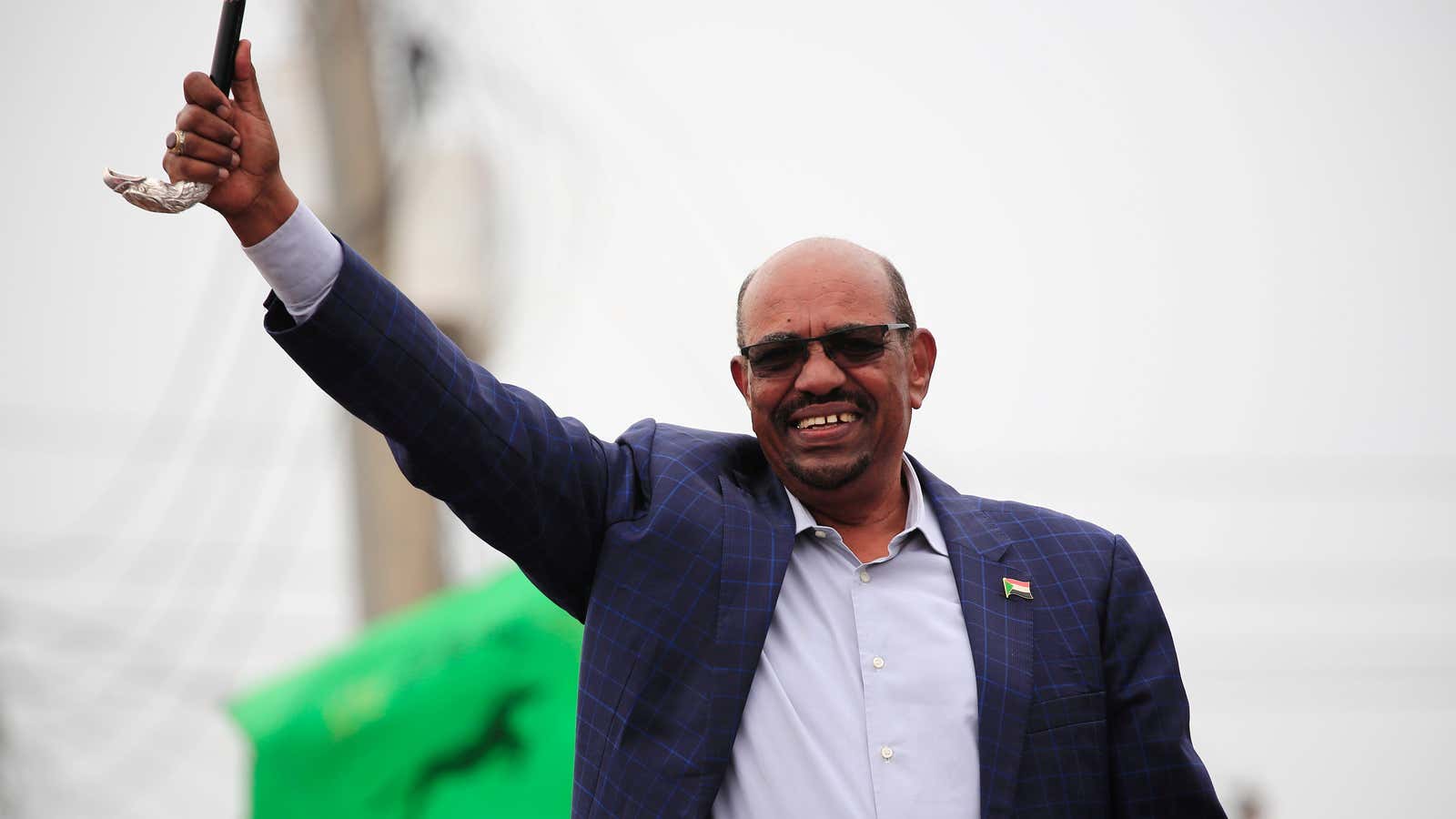

The north-east African nation’s declining economic and political reality has also not been helped by the presidency of Omar Hassan al-Bashir, who has ruled over the country for over 28 years. Al-Bashir is wanted by the International Criminal Court for committing crimes against humanity over the conflict in Darfur, which started in 2003 and led to the killing and rape of thousands of civilians and the displacement of hundreds of thousands of others.

But as much as Sudan was isolated by the sanctions, their removal now signals to the political adroitness of al-Bashir. For one, Sudan has made itself indispensable to the Saudi-led coalition that has been waging war in Yemen since 2015. The government dispatched hundreds of its troops to fight in Yemen, incurring heavy losses even as the Saudis and Emiratis mostly relied on bombing from the air.

As The Intercept recently reported, in return for doing the “dirty work,” the UAE put its substantial diplomatic weight in Washington DC behind Sudan. Yousef al-Otaiba, the UAE’s ambassador to the US is especially close to Jared Kushner, president Donald Trump’s son-in-law who is also in charge of forging peace in the Middle East. After Sudan cut relations with Iran, both Saudi Arabia and the UAE lobbied president Barack Obama to normalize relations with the country—culminating to Obama approving an executive order before leaving office to temporarily ease the penalties.

Bashir has also courted American sympathy by recently cutting relations with North Korea and enforcing all the UN-proposed sanctions against the country.

For now, Sudan’s government has welcomed the US decision as “historic.” Despite that, Sudan has a long way to before it can fully improve on human rights and governance, and remove the limitation on religious, political, and press freedom. And even though the state still remains on the US list of state sponsors of terrorism, Sudanese people now hope that the decision will boost the economy and improve livelihoods.