The US government is finally acknowledging the flame retardants in your furniture and baby products are not just ineffective, but also dangerous

The US agency in charge of protecting consumer safety just took the first step towards banning a class of flame retardants that were, up until very recently, nearly ubiquitous. So ubiquitous—mostly in children’s clothes, baby toys, and upholstered furniture—that the vast majority of the US population has measurable quantities of it in their blood.

The US agency in charge of protecting consumer safety just took the first step towards banning a class of flame retardants that were, up until very recently, nearly ubiquitous. So ubiquitous—mostly in children’s clothes, baby toys, and upholstered furniture—that the vast majority of the US population has measurable quantities of it in their blood.

The US Consumer Product Safety Commission published a notice in the Federal Register on Sept. 28 warning that, based on “overwhelming scientific evidence” that organohalogenated flame retardants “present a serious public health issue,” using them is “ill advised.” Years of peer-reviewed research have associated exposure to this class of flame retardants with reduced fertility, lower IQ in children, developmental problems, early puberty, thyroid problems, and cancer.

Manufacturers should eliminate them from their products, the commission wrote, and people—especially pregnant women and children—should take precautions to make sure the flame retardants aren’t in anything they buy. The warning was prompted by a 2015 petition signed by the American Academy of Pediatrics and other health groups urging the ban. The commission also voted 3-2 to begin the process of banning the class of compounds.

Flame retardants don’t even work

Flame retardants are a particularly North American problem; in 2009 the US Centers for Disease Control found that, on average, Americans had levels of the chemicals in their blood three to 10 times higher than people from various European countries.

The debacle started in the mid-1970s, with a group of powerful industries more or less colluding to promote the use of fire retardants in furniture production, according to a major investigation by the Chicago Tribune:

The tactics started with Big Tobacco, which wanted to shift focus away from cigarettes as the cause of fire deaths, and continued as chemical companies worked to preserve a lucrative market for their products, according to a Tribune review of thousands of government, scientific and internal industry documents. These powerful industries distorted science in ways that overstated the benefits of the chemicals, created a phony consumer watchdog group that stoked the public’s fear of fire and helped organize and steer an association of top fire officials that spent more than a decade campaigning for their cause.

In 1975, California enacted “Technical Bulletin 114,” a law that required foam-filled furniture to withstand 12 seconds of exposure to an open flame without catching on fire. That effectively required furniture manufacturers to douse their products in flame retardants.

For manufacturers who wanted to sell their furniture nationally, it didn’t make sense to produce California-specific products. So flame retardants were often injected into polyurethane foam that filled couches, chairs, and mattresses (and gym mats, leading to particularly high exposures in American gymnasts) sold across the country. The chemical industry, wanting to protect a lucrative new market, lobbied against pulling the products long after studies began linking flame retardants to health problems.

The thing is, they don’t even work to prevent fires. Government tests in 2009 concluded that they don’t “provide any significant protection,” according to the Tribune.

No longer required—but still being used

If you bought your upholstered furniture before 2011, there’s a good chance they are full of flame retardants. In a 2012 study of 100 couches, the Green Science Policy Institute (an advocacy group that spearheaded the 2015 petition on flame retardants) found flame retardants in all but one couch they purchased in California and in 81% of couches purchased in other states.

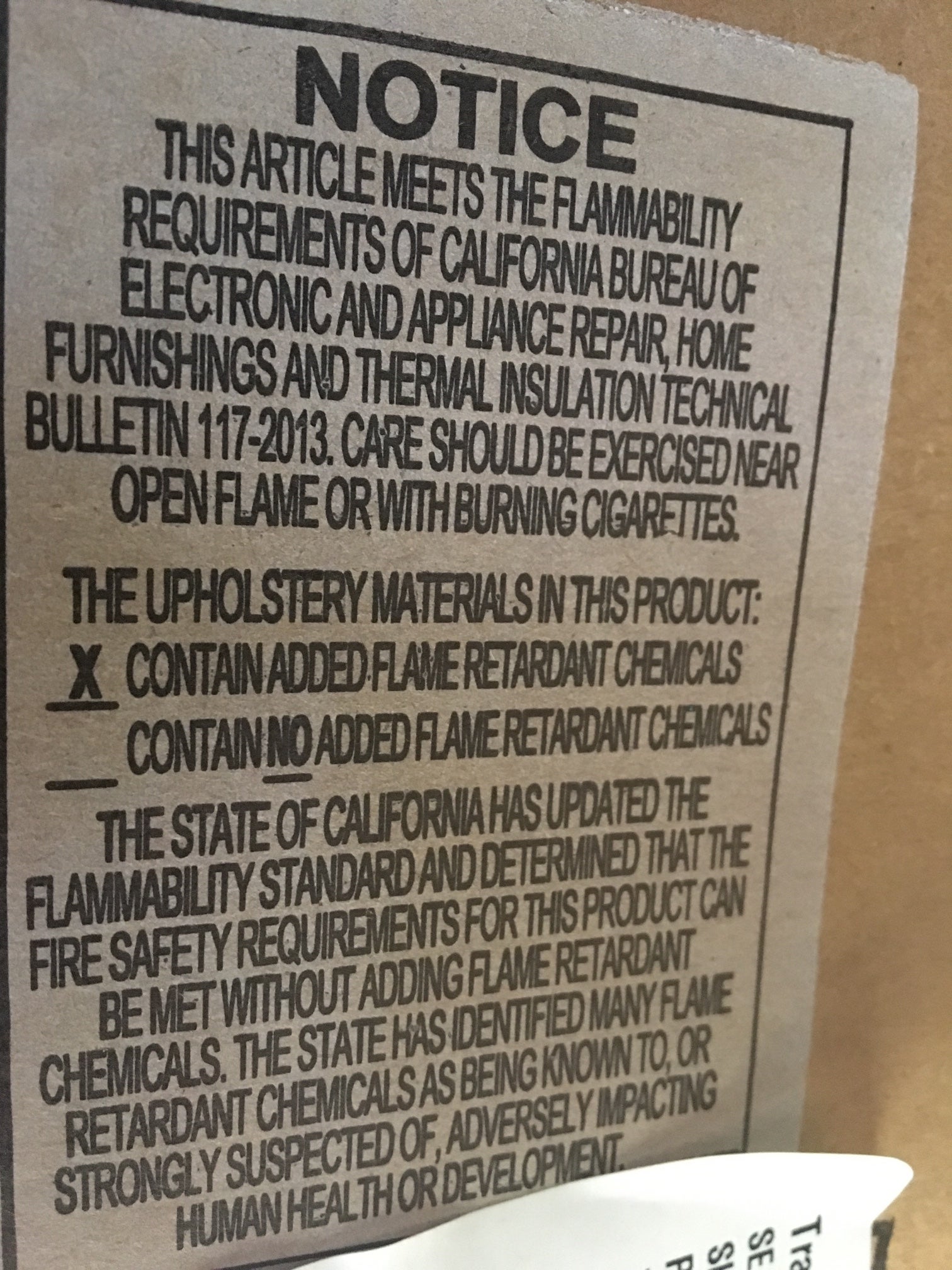

California amended its rules in 2013, lifting the de facto requirement, but that doesn’t mean the chemicals have disappeared from products. The new law requires furniture companies to explicitly label whether their products contain flame retardants or not. Most furniture now carry tags referring to “California Technical Bulletin 117-2013” and a check box-style label indicating if they have flame retardants or not.

This reporter turned over her desk chair while writing this article and found that it is indeed full of flame retardants. (Our facilities team has been alerted and is looking into it.)

Many major furniture manufacturers have moved away from using them, and a major trade association for furniture makers has issued statements supporting their elimination.

“The problem now is educating designers and architects,” who think they’re making the right choice by requesting flame-retardant furniture, says Arlene Blum, founder of the Green Science Policy Institute.

Ban in the hands of a Trump appointee

In a strongly-worded statement, Elliot Kaye, one of five US Consumer Product Safety commissioners, condemned the “completely irrational” US system of chemical regulation that allowed flame retardants to proliferate for so long.

The US takes an “innocent until proven guilty” approach, allowing most chemicals on the market without safety-testing them. When a problem is found, it is often after years of widespread use, and banning a chemical requires a vast amount of scientific evidence of harm.

“As a policy maker, and more importantly, as a parent, I am horrified and outraged at how chemicals are addressed in this country,” Kaye said. “It is completely irrational that we wait for children to be poisoned before the government is allowed to step in.”

The commission’s vote to begin the potentially years-long process of banning flame retardants is promising, but it may be the last gasps of the regulatory efforts of a previous administration. One of the commissioners who voted to support the ban was Marietta Robinson, an Obama-era appointee. On Oct. 1, her seven-year term expired, and Donald Trump’s administration replaced her with an attorney who has a history of defending companies accused of selling unsafe products.