The humble fingerprint—which revolutionized crime-fighting—is getting a molecular upgrade

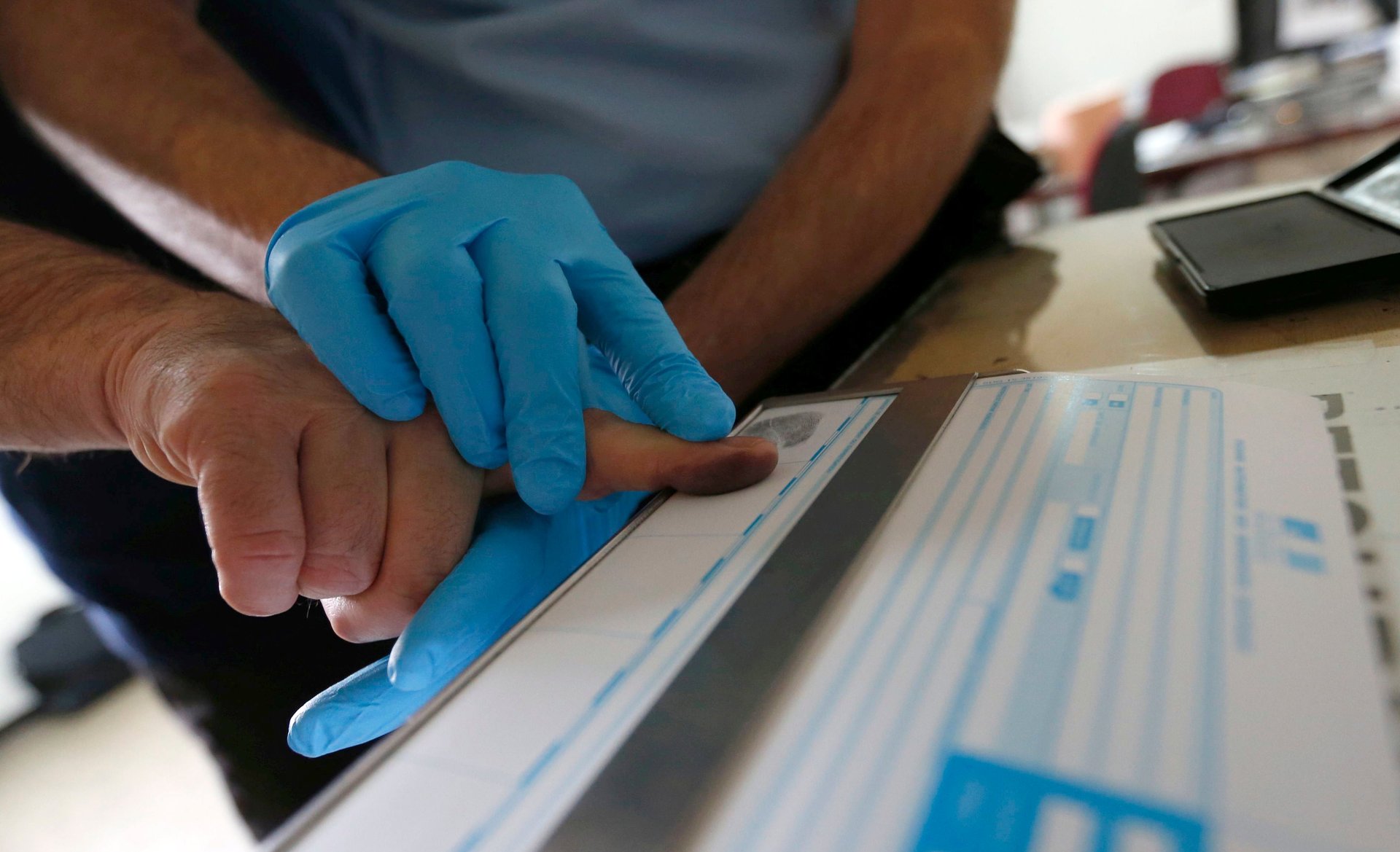

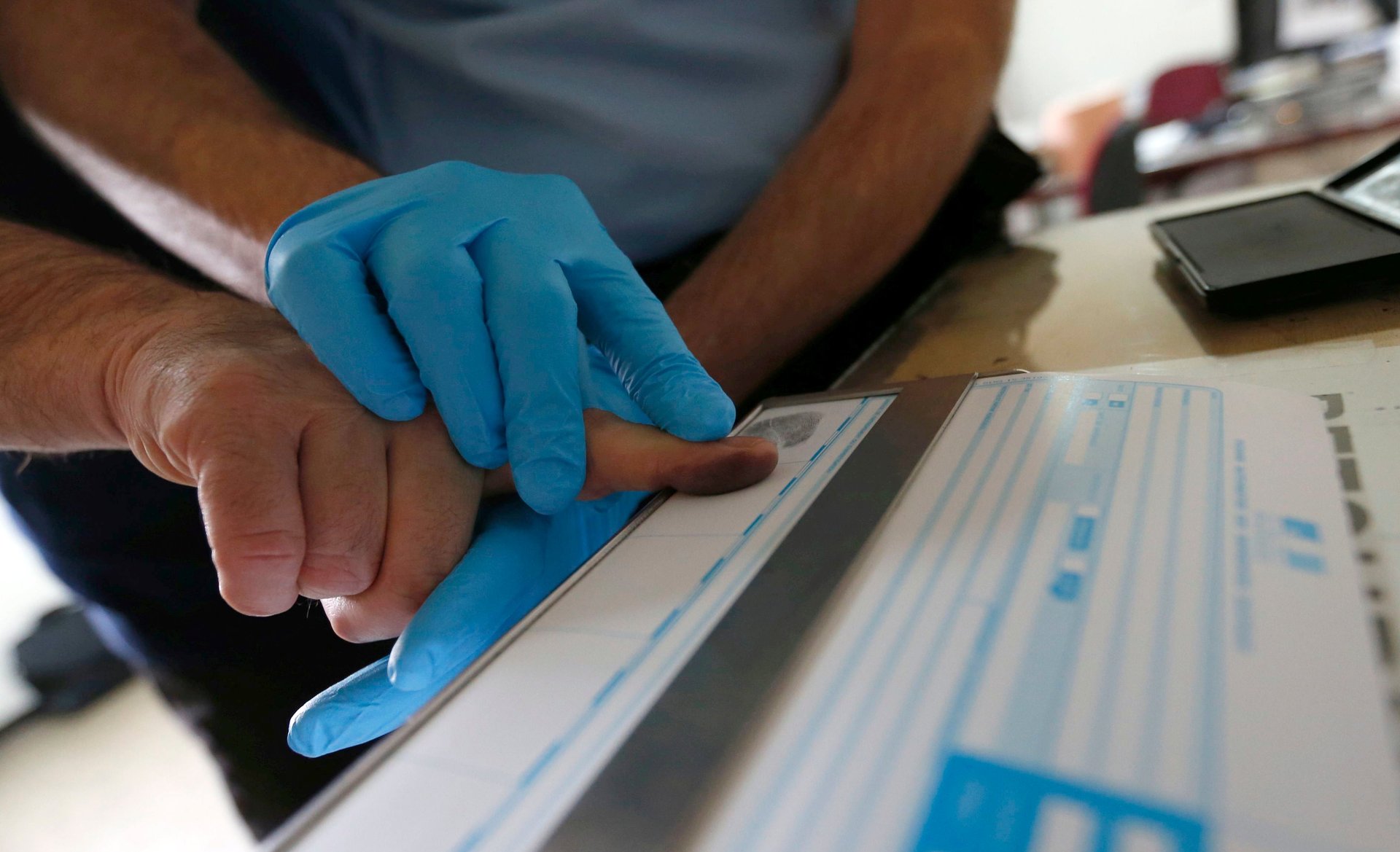

The science of fingerprinting has progressed little since it was first used to convict an Argentine woman for the brutal murder of her two small children in the summer of 1892.

The science of fingerprinting has progressed little since it was first used to convict an Argentine woman for the brutal murder of her two small children in the summer of 1892.

But if the print is smudged, or a match can’t be established, then the fingerprint is pretty much useless. Even a perfect print is only good for placing a person at the scene of a crime—and not much else.

Yet, as Simona Francese, of Sheffield Hallam University, explained to the BBC, a print could be so much more. It “contains molecules from within your body but also molecules that you have just contaminated your fingertips with, so the amount of information there potentially to retrieve is huge,” she said.

So she and her team have been working with the UK’s West Yorkshire Police on a pilot program that combines fingerprint analysis with the gold standard of material analysis, a technique called mass spectrometry, to design a way to extract more of that latent information from prints. The practice involves placing a sample in a large machine that then pulverizes and subjects it to electric and magnetic fields. By measuring how different molecules react under these conditions, scientists are able to identify a wealth of information from the tiniest of matter.

Francese explained to the BBC in 2014:

By looking at the proteins found in the mark, we can find out if the suspect is a male or female. We can understand whether or not a person has dealt drugs or actually taken drugs. We can detect ingested substances, so we may be able to reconstruct what that person has been eating just before committing the crime.

And this is regardless of how old the print is—in one instance, her team was able to identify a blood sample from a 30-year-old print. Any of this information can go to establish, cause, motive, or the whereabouts and involvement of the persons of interest in the case.

After conducting more than a few trial runs over their five years working with Yorkshire police, Francese and her team feel the technology ready for deployment, but she does urge caution; the process is still complicated and expensive, so probably not suitable for every street-level smash-and-grab. But she said the science is sound and the value great enough that she hopes her technology will be deployed immediately in high-profile, high-impact cases, like those involving murder or rape.

And Neil Denison head of regional identification services for the West Yorkshire Police agrees wholeheartedly, he told the BBC, “Criminals are getting better at what they do, and we need to keep up with them.”