India, currently the world’s fourth-fastest growing economy, hasn’t exactly had a dream run this financial year.

Following two consecutive quarters of a slowdown in GDP expansion, brokerage houses and multilateral institutions have revised their forecasts for the rest of the financial year, too. On Oct. 10, the International Monetary Fund said it expects India’s GDP to grow by 6.7% in the current financial year. Most other organisations also expect India to grow at 6.7% in FY18 compared to earlier estimates of over 7%.

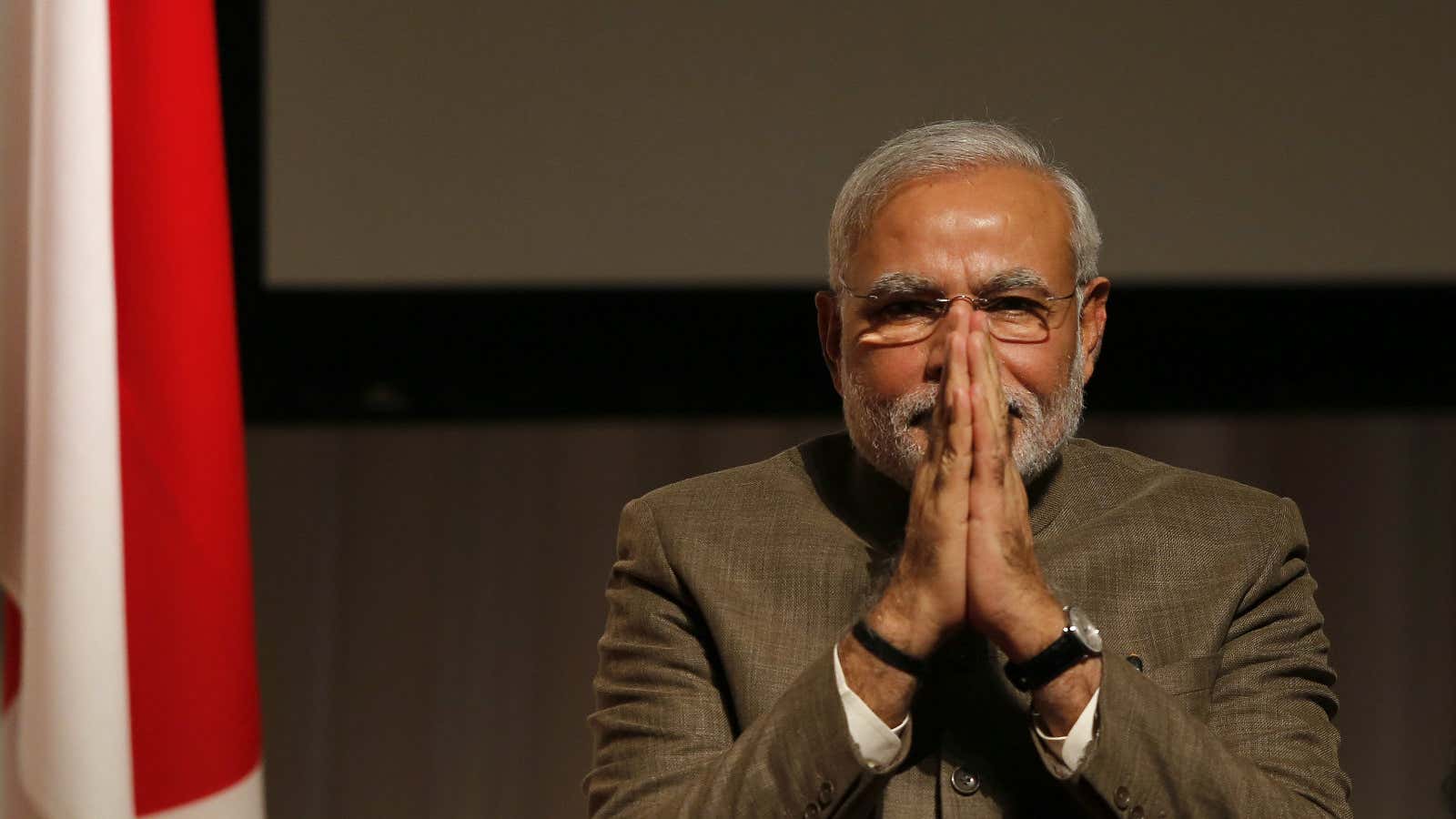

Meanwhile, after several attempts at assuring the country about the well-being of its economy, the Narendra Modi government has finally accepted that it is battling a slowdown.

In the face of adverse GDP data, falling investment demand, declining industrial production, rising unemployment, and weakening consumer confidence, the government is trying to put together a revival roadmap.

After meeting for the first time on Oct. 11, the prime minister’s economic advisory council has outlined 10 areas it will work on for this. These cover the usual suspects like employment and job creation, fiscal framework, monetary policy, public expenditure, and institutions of economic governance, among others.

Despite these interventions, there’s a problem: Indian corporates aren’t ready to loosen their purse strings just yet.

A study by credit rating agency India Ratings and Research reveals that any meaningful addition to capacity expenditure (capex) is more than two years away—i.e. only after 2019-2020. Capex involves expansion of projects and services by companies and, therefore, is an indicator of the overall economic environment.

The introduction of the goods and services tax (GST) in July has disrupted the flow of working capital flow in India, putting the economy under stress. Weak consumption demand and global overcapacity have added to corporate India’s woes, the report says.

This slowdown in investment is mainly led by stressed companies (especially in the infrastructure, metals, and power sectors). Many of them have cut down on capex between FY12-17 and are unlikely to spend in the next two-three years, dragging down the investment recovery.

The overall private sector capex—mainly on maintenance and upgrades, sidelining long-term projects—will grow by Rs1 lakh crore every year till fiscal 2020, at an annual rate of between 5% and 8%.

Meanwhile, companies are also finding it difficult to raise loans. Saddled with toxic loans of close to Rs10 lakh crore, Indian banks have been selective in lending. In recent months, the government and the Reserve Bank of India have taken several steps to clear the mess in the banking sector, including taking some of the large defaulters to the bankruptcy court. Nonetheless, it will be a while before the bad loan problem is resolved.

And that doesn’t help a government in a hurry to turn around the economy. Because, lenders already struggling with cleaning up their books are bound to view big-ticket expansion plans as high-risk.

Ultimately, the horizon doesn’t look cheerful for the Indian economy.