This is why Nazi speakers should be allowed to come to college campuses

Ann Coulter, Ben Shapiro, Richard Spencer, Charles Murray, Betsy DeVos, Milo Yiannopoulos. The list of controversial, provocative, or politically divisive guest speakers on college campuses is long and growing. Often, they don’t even get to speak: colleges rescind invitations, or the crowds refuse to let them get a word out. Two speakers were shouted down by student protesters at different universities just this week.

Ann Coulter, Ben Shapiro, Richard Spencer, Charles Murray, Betsy DeVos, Milo Yiannopoulos. The list of controversial, provocative, or politically divisive guest speakers on college campuses is long and growing. Often, they don’t even get to speak: colleges rescind invitations, or the crowds refuse to let them get a word out. Two speakers were shouted down by student protesters at different universities just this week.

But there is value yet in letting polarizing figures—however seemingly discriminatory, racist, or otherwise offensive they are—come to campus. A new report (pdf) yesterday from the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, or FIRE, found that, contrary to popular opinion, college students aren’t wont to blindly shout down people with whom they disagree. There might actually be a dialogue taking place.

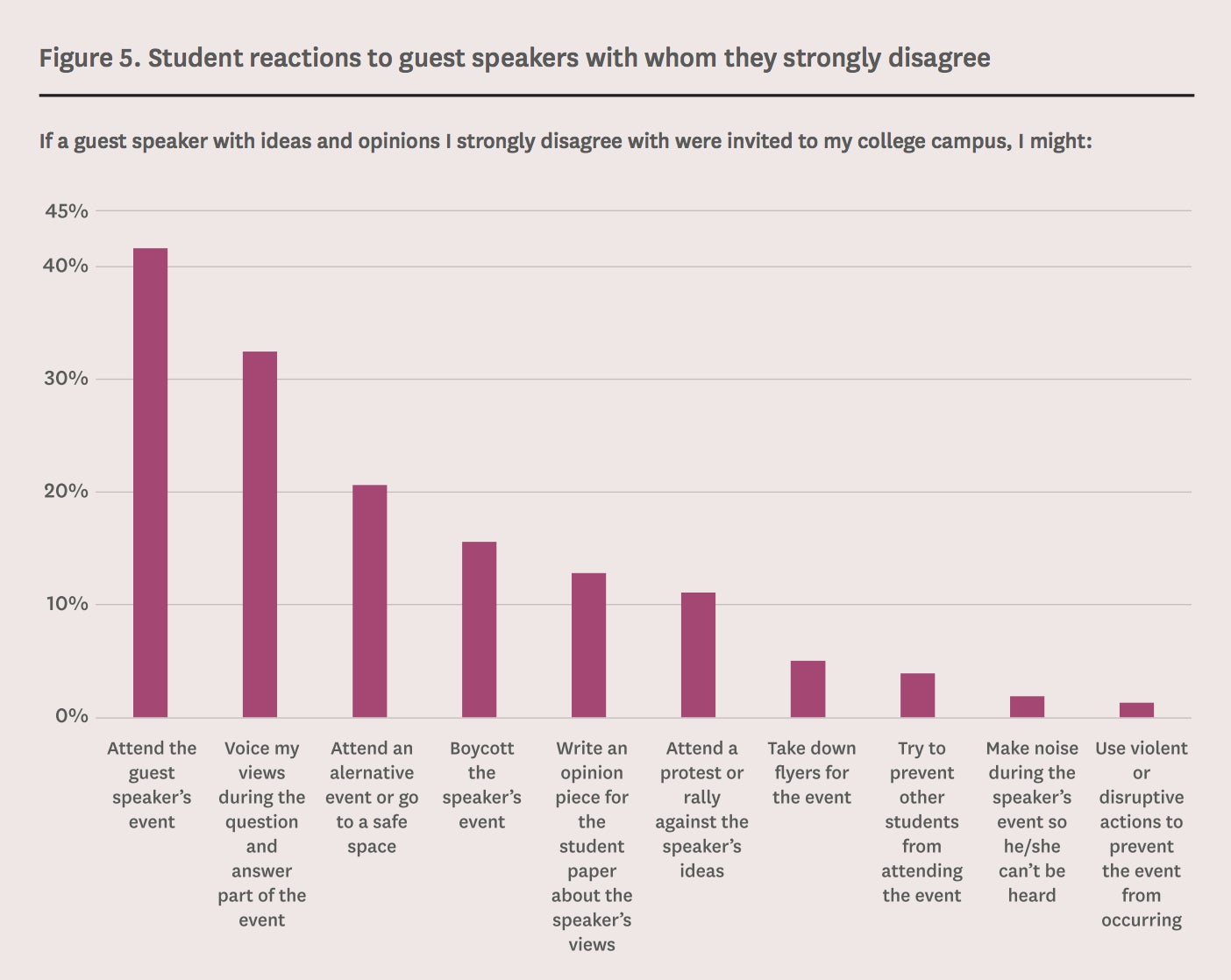

When confronted with a speaker with whom they “strongly disagree” coming to campus, most students will still attend the speaker’s event—and many would prefer to express their contrasting views during Q&A sessions at the event. If the point of going to university is to be exposed to a wide-ranging set of opinions, it seems students are eager to take the opportunity.

Boycotting, protesting, or actively trying to hinder a controversial speaking event are much less considered options for students who disagree with a speaker’s presence. And students would rather voice their views by writing an op-ed for their student newspaper (13%) or post on social media about the speaker (15%) than try to prevent others from attending (4%) or make noise during the event (2%).

Only 1% of students would actually consider disrupting a guest speaker with violent action, the FIRE survey found. That stat is a direct contradiction to a Brookings report last month that said 19% of US students consider it acceptable to use violence against an offensive speaker—a finding that has since been attacked by some polling experts as “junk science” because the survey was not administered to a randomly selected sample of college students, but rather an opt-in online panel.

Elite American colleges already skew overwhelmingly liberal, with more privileged students being all the more likely to scoff at viewpoints they don’t support (paywall). FIRE’s survey results show that having offensive or disagreeable speakers come to campus—though they might incite protest from the most staunch activist groups—gives the bulk of students a chance to hear others’ viewpoints and engage in meaningful conversation with them; it also shows that students are not the easily-antagonized bunch of group-thinkers that they’re often painted to be.

That said, there is a line, which many students do draw, between thought-provoking discourse and sheer provocation.