The Middle-Eastern American writer behind Marvel’s Iceman, the most visible gay superhero yet

Sina Grace started studying superheroes seriously when he was four years old. “I’d copy Batman stories, and draw them on printer paper,” says the storyteller from Los Angeles, California, now 31.

Sina Grace started studying superheroes seriously when he was four years old. “I’d copy Batman stories, and draw them on printer paper,” says the storyteller from Los Angeles, California, now 31.

With time and practice, this habit developed into a skill. Now, Grace is paid to create the comic books he read with such relish as a kid.

He even developed a superpower of his own: Grace is living life as himself. “I’ve been engaging in this grand experiment,” he says, “where I try to live life exactly how I want to, and accept all the consequences for that.”

A hero’s journey

Grace writes Marvel’s Iceman. Or, more precisely, Grace writes the latest iteration of Iceman, a character who’s been around longer than he has.

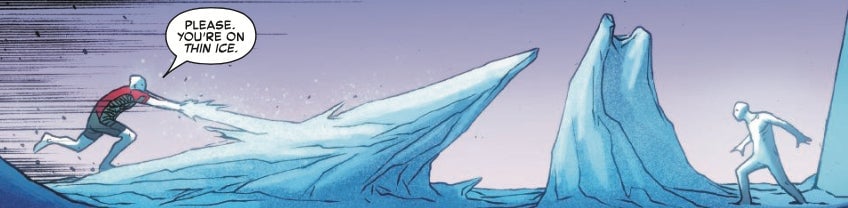

Iceman is the X-Men mutant superhero whose real name is Robert Louis Drake aka Bobby Drake, and whose power is freezing enemies into submission. He was originally created by writer Stan Lee and artist Jack Kirby, and first appeared in the first issue of X-Men in September, 1963.

Bobby Drake is a half-Jewish and half-Catholic mutant from Floral Park, Long Island, who discovered his super power early in life when he couldn’t stop feeling chilled, according to the Marvel lore. He’s got problems with his parents, who can’t relate to this predicament. He isn’t alone, however. Drake was discovered by professor Charles Xavier, who invited the teen to his school for gifted youngsters, where Drake met others like him. As an adult, Drake teaches other mutants at the X Institute for superhero studies, and, under his nomme de guerre, “Iceman,” fights bad guys with a bunch of mutant buddies, each with different powers but who all feel similarly outcast from the society they’re saving.

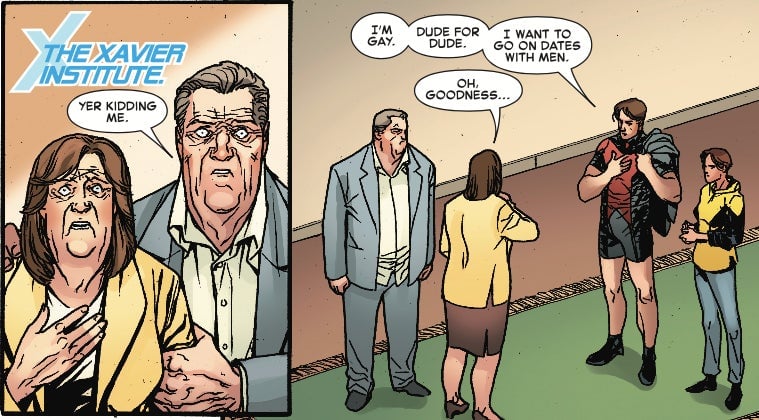

Long-running comic book superhero stories are told by many writers over time, with various story arcs encompassing different themes and adventures. In Grace’s Iceman—the series began in June, and the latest issue is out on Nov. 1—Bobby Drake is a hero dealing with his sexuality anew as an adult meeting a younger, time-displaced version of the character, written in 2015 by Brian Michael Bendis, who reveals to current Drake that he’s gay.

This likely sounds confusing to the uninitiated but comic book fans are accustomed to serial reading that goes in all directions, with the same characters living multiple lives as imagined by different writers, sometimes simultaneously, often over decades. So, for X-Men fans, the notion of an older Iceman meeting a younger Iceman and discovering from the millennial that it’s cool to be gay is totally within the realm of possibility.

At the time Iceman came out to himself, Grace was 29, young but already something of a comics old-timer. He went to his first comic book convention when he was 12 and immediately started soliciting advice on how to get work in the business.

Later, Grace attended high school in Santa Monica and interned with a comic book company in LA, hopping on the bus after classes to go learn from masters. Then he studied creative writing at the University of California-Santa Cruz, where he wrote and illustrated a thesis that’s still enthusiastically recalled at the local comic book shop Comicopolis, where Grace is considered a local star. (I went in to buy physical copies of Iceman 1-6 , and the owner proudly claimed Grace as a local, though he’s been back in LA many years now).

After graduation, Grace wrote and drew his own stories, worked on independent comics that were well-received but not lucrative, and did freelance writing and illustrating (children’s books were common), but he wasn’t earning a living in the arts. To survive, he worked in retail, selling fancy clothes to ladies at Bloomingdales. He recalls thinking, ”Anything can be better than what’s happening now.”

The storyteller decided he’d give his all to comics by getting a “real job” in the industry. In 2010, he became an editorial director at Skybound Entertainment, where he worked on The Walking Dead book. But after a couple of years he was still frustrated that he wasn’t making a living off his own artistic production, so Grace took the advice of artist friends and sacrificed for his passion: “I was told that living hand to mouth isn’t regrettable, it’s worth it,” he says.

He started seriously hustling, doing more readings, attending more conventions, forging ties with comic book shops, taking more freelance work, living off less and less while producing more and more. He started pestering Marvel editors with story pitches. In 2015, they offered him the opportunity to write the new-old Iceman, a superhero discovering his sexuality.

Writing a new story arc for an existing, beloved character is challenging but also one of the great honors in comics. The gig is a dream come true for Grace, and this in particular is a tale he is well-equipped to tell.

Grace on Grace

Grace has plumbed the depths of his own psyche and explored his sexuality before, like in the 2017 graphic novel Nothing Lasts Forever, which chronicles (in the form of a journal) a year of heartbreaks, and in 2012’s Not My Bag, the delightful tale of employment, love, artistic dreams, and the search for personal destiny. He examined his own psychic flaws in the graphic novel Self-Obsessed and 2015 web comedy series by the same name, and in the 2011 Image Comics series L’il Depressed Boy.

Grace has contemplated and combed through a “mess of memories,” he says, illustrated, written, and collaged them for consumption, turning them into funny, bittersweet tales. They are personal stories about a gay, high-fashion-loving, comic-book nerd of Iranian descent, making his way in a sometimes hostile postmodern world, and defending himself with humor.

Yet they are also imminently relatable because they’re stories about a guy looking for love and meaning, earning a living, dreaming, discovering his path, and trying to live a considered life. Even if the details differ between Grace, you, and I, at the core of his work is something universal: the story of a person growing up.

Grace and the character he’s writing, Bobby Drake, are obviously different. The writer has rules to ensure that he doesn’t indulge “foolish writerly tendencies” and delivers Drake, not Grace. Among these rules, Iceman can’t be attracted to the same type of guys as the writer (big, bearded, flannel-shirt-wearing). “I owe it to the canon and readership to create a very specific Marvel story,” Grace says gravely. “This book isn’t my playground.”

Also, unlike Drake, Grace never felt or feigned attraction to women. The writer began telling people about his sexual orientiation slowly through high school and college, starting with close friends, then his sister and mom, “and it all built up to a particularly dramatic coming-out with my dad on my college graduation weekend,” he explains.

These experiences and those of Grace’s friends inform aspects of Iceman. For example, the questions people ask and their reactions to homosexuality do make their way into the comic book. “The lines in the series that go like ‘I have no son’ or ‘my son is dead,’ were things my friends had to hear when they came out to their parents,” he says.

Still, Drake is not Grace. The superhero is more mutable than his writer. “I do crib a lot from my own experiences being Middle Eastern and gay,” Grace says. “But Bobby’s a more interesting figure than me because he can pretty much pass as a non-mutant, cis-white male. I don’t know how much I’ll explore that further, but it certainly lends itself to why he waited so long to confront his sexuality.”

What Grace does share with Drake is a fondness for puns. “Iceman tells bad jokes and I do too. He hides behind humor, which is something I can understand,” Grace says.

The bad “dad jokes,” which Iceman is famous for and Grace continues to make a feature of the character, were how Iceman dealt with the awkwardness of his own existence before he came to know himself, or that’s how the writer sees it. “Iceman uses humor to heal and hide.”

Iceman wasn’t Grace’s favorite mutant when he was a kid. Bobby Drake didn’t seem fully formed or memorable, like Wolverine, say. When writing Iceman, Grace came to understand that blankness: the character had been shielding himself from the truth about who he really was.

“In a broad sense, the character’s sexuality doesn’t influence him as a superhero. It doesn’t change the action and adventure or the fights. But his psychology does matter,” Grace says. Obviously, how Drake feels about himself and his relationships influences his life and work, just as it does for real people in the real world. The fact of being gay doesn’t change Iceman’s abilities, but the extent to which he is at peace with his sexuality can.

Even now, Iceman, who Grace calls “an omega-level mutant”—meaning he has potential to be an exceptionally powerful superhero—can’t fully inhabit his powers because he’s still somewhat of a mystery to himself. That could soon change, however. “There have always been hints that he could be a weapon of mass destruction, but his powers have been stifled at times. If his mind can be freed, he’ll tap into those powers,” Grace says knowingly.

Born this way

Like Iceman, Grace feels himself to be different from mainstream society, but he is not entirely alone. Comic book heroes are traditionally big, tough, straight, white men, sure—but readers have long been very diverse. The industry is starting to recognize as much and the stories are changing.

In 2015, the Huffington Post published “a brief and wondrous guide to contemporary queer comics,” naming 18 LGBT creators. Each has a different style but there is a unifying theme, expressed most succinctly by illustrator and comic book creator Kristina Stipetic. She explained the impetus for her work, saying, “I couldn’t find the stories I wanted to read, so I took up writing.”

In March 2017, Matt Baume at Out declared that a “queer comic book revolution” is happening. “From the indie level up to major publishers, creators are beginning to veer outside the long-standing default straight-male gaze—a shift in focus that mirrors that of mainstream culture,” he wrote, noting that Marvel in 2015 introduced a transgender character, Koi Boi, and in 2016 DC Comics’ Wonder Woman came out as bisexual at age 75.

Long before the revolution, however, the X-Men mutants were designed to tap into a universal feeling of outsiderness among the historically oppressed, Grace explains. ”Whether it’s race, gender, sexuality, or something else people are born with, can’t change, and are told is bad, they can relate to the mutants, who represent a safe place where they can be themselves and that’s what people love about the characters,” he says.

The heroes’ mutations are metaphors. What makes them strange to others also makes them strong and if they can fully accept and inhabit their mutant selves, they can reach their full potential.

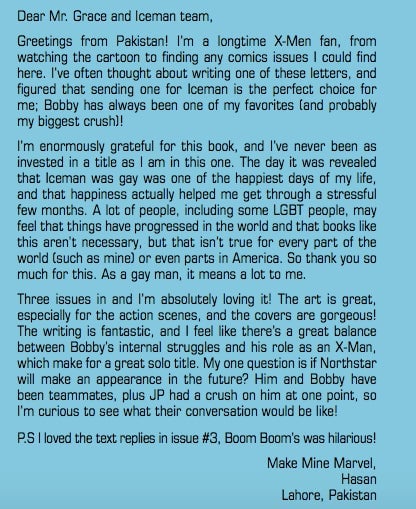

These fictional characters are studied by kids and adults around the world, and they inspire many, not just the lucky few who end up writing comics. Grace says he is amazed by the outpouring of sincerity in the emails, letters, and drawings from fans in Canada, Pakistan, and beyond, thanking him for his inspiring writing.

He’s happy to be of service, offering what he knows personally of the hero’s journey. “Life is short,” Grace says. “At one point, I got sick, my grandmother died, and I hit a huge wall. I realized I needed to strip myself of everything else to see what I was made of—relationships, stuff—to find out what really matters.” For a while, he slept on a chair, and discovered he didn’t even really need sleep, and this helped him feel free.

In college, Grace made the uncommon choice to not choose between illustration and writing, and set out to be a professional storyteller in all styles, open to any form that might work. The approach seems to be working.

Someday, he’d love to write a graphic novel that’s not autobiographical, and front a punk band–he says he can’t sing or play guitar, but still is interesting in trying to be a rock star. Still, Grace is reluctant to set a plan fully in stone for his favorite character, which is himself.

For now, his mission is evident: keep exploring the possibilities Iceman has opened up for him. After all, Grace has been studying superheroes since he was a kid. “All I’m here to do,” says Grace, “is try to tell an action story with major feels and some good fights.”