A judge is poised to decide whether graffiti can be protected by law

Graffiti’s transformation from a kind of vandalism to a high art form is almost complete. In the last half century, street art has evolved from a stain on neighborhoods to a tourist draw and the toast of museums and galleries, embraced in pop and high culture.

Graffiti’s transformation from a kind of vandalism to a high art form is almost complete. In the last half century, street art has evolved from a stain on neighborhoods to a tourist draw and the toast of museums and galleries, embraced in pop and high culture.

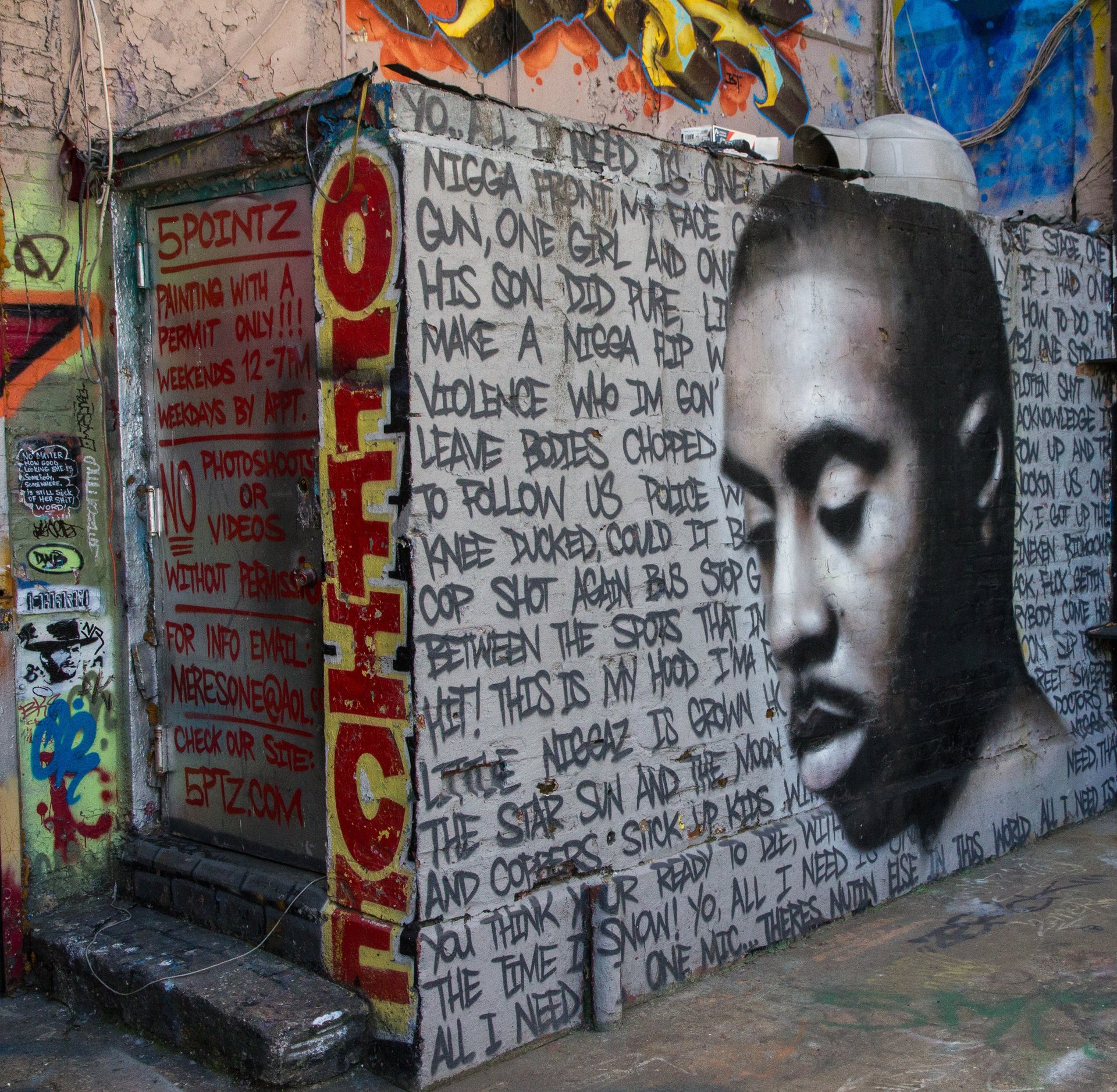

As its market value rises, the controversial art form is also increasingly the subject of legal disputes with developers and property owners about its preservation and value as intellectual and cultural property. This week, a group of 20 New York street artists are in federal court, fighting developer Gerald Wolkoff, who in 2013 whitewashed 5Pointz, his iconic building in Long Island City (LIC), a neighborhood in Queens just across the East River from Manhattan. The building’s facade served for years as an outdoor aerosol-art exhibit space and had become known as a graffiti-Mecca for its many murals.

Wolkoff granted permission to artists to paint on the building in 1993, when Long Island City wasn’t hot property. In 2000, PS1 in LIC, a nonprofit started in 1971 to use derelict buildings for art (PS1 stands for “Public School 1”; the nonprofit was housed in a former public school building), became affiliated with the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan, turning into MoMA PS1. That made the location more attractive to artists. By 2002, this part of western Queens was becoming cool, and Wolkoff gave an artists’ group his blessing to make 5Pointz a hub, along with keys to office space in the building.

Fast forward to 2013, New York real estate was exploding. The building’s location was highly desirable; Brooklyn and Queens were flourishing and New Yorkers needed to expand into new territory. They chose the old manufacturing hub, LIC, which by 2016 was “home to New York’s building boom,” according to the Financial Times (paywall). The New York Times in 2015 wrote (paywall) about LIC “for the good commute.” It was also attracting the fashion industry “for its price and proximity.”

Wolkoff saw the change happening and wanted to cash in. But he knew the artists were attached to the building. In October of that year, he stealthily whitewashed 5Pointz at night. Soon after, the building was demolished and Wolkoff’s companies began work on two luxury-apartment high-rises that would capitalize on the locale’s street cred by referencing the graffiti and incorporating street art into the decor.

In the lawsuit—a consolidation of two cases brought by various artists against the developer’s companies—the muralists argue that their work contributed to the improvement of LIC. They claim 5Pointz was of such prominent international stature that Wolkoff should not have destroyed it without permission and proper notice, providing time for them to salvage what they could, based on the Visual Artists Rights Act of 1990.

That law grants artists “moral rights” to works of prominent stature. Basically, it gives artists the ability to sue for damages if prominent creations are mutilated or destroyed—even if those artworks are owned by someone else. A Harvard Law School guide on the statute explains that the legal remedies available for moral-rights violations include $500 to $20,000 in damages per artwork.

The 5Pointz muralists are suing over the destruction of at least 350 paintings, so there’s a lot of money at stake, apart from the case being significant to the street-art movement, the contemporary art market, and property developers. The artists say that they should have been allowed to salvage what they could for museums and sales.

Whether the 5Pointz murals are “prominent artworks” qualifying for legal protection is a question a jury must resolve. To convince the panel of 12, each side in the case will present dueling art experts who will explain the current state of street art.

The art expert called to the stand by the artist group will no doubt point to the prominence of Banksy and Shepard Fairey, household names whose works are displayed in museums, and whose contributions to building facades and retaining walls, at this point, drive up property values. Perhaps he or she will mention the late Jean-Michel Basquiat, who began as a graffiti artist in New York’s Lower East Side in the 1970s before becoming famous; one of his paintings sold at a Sotheby’s auction in March 2017 for $110.5 million.

Meanwhile, Wolkoff’s expert will surely try to distinguish these stars from the muralists in the suit, arguing that their work doesn’t reach the dizzying heights of great street artists. For example, Jonathan Cohen, who organized the 5Pointz artists in 2002, goes by the tag Meres1. He isn’t a household name. But, Cohen insists on his website, Banksy knows of his “selfless efforts” at 5Pointz. Cohen’s site also notes prominent corporate connections, including Louis Vuitton, Nikon, Nespresso, Fiat, Facebook, Google, Samsung, and Smartcar.

The trial will take place in a New York federal court, presided over by Frederic Block, who is something of a renaissance man with a feel for the streets, or at least that’s the impression I got when I read his book and spoke to him last month.

On Oct. 10, Block released his first novel, Race to Judgment, a “reality fiction” about the complex interactions between Brooklyn’s racially, ethnically, and economically diverse citizens vying for power and space in the city. The judge also recorded songs to go with the book, providing a soundtrack for his protagonist. When Block and I spoke, we didn’t discuss this case, but it’s safe to bet he has some appreciation for the efforts of the visual artists involved.

Indeed, last April, Block denied Wolkoff’s attempt to dismiss two different 5Pointz cases. In his decision, Block cited the expert who testified on behalf of the artists, who noted that many of the muralists were internationally known and supported by museums, academics, celebrities, the media, and the public. Block did reject the artists’ attempt to sue for damages based on claims of emotional distress, writing that developers “did no more than raze what they rightfully owned” and didn’t engage in “outrageous or uncivilized conduct.” However, he also allowed the case to proceed to a jury trial.

At the time, Wolkoff told the New York Times the decision to allow the case to continue was “mind-boggling.” Graffiti isn’t created for preservation, he said, and the artists couldn’t have expected their works to stay up forever since they were constantly getting covered up anyway. Wolkoff claimed to have developed an expertise in street art through his relationship with the 5Pointz artists over the decades, and oferred his view of the form:

They call it bombing, and the next artist goes over someone else’s work, They painted over their own work continually, and it goes on for years. That’s the idea of graffiti. There were tens of thousands of paintings there, over the years, and they’d last for three or six or nine months.

Wolkoff feels betrayed by the artists he thought he was helping by lending them his wall to bomb. He cried when the building came down, he confessed, and said he would bring back more street artists to paint at the location after the renovation—just not those who sued.

There have been similar cases before but they have settled. Katherine Gibbs created “The Illuminated Mural” in Detroit’s North End with a hundred gallons of technicolor paint and $33,000 in grant money in 2009. A few years later, the development company Princeton Enterprises acquired the building and planned to mar the massive painting with new windows. In 2016, Gibbs sued, claiming that federal law protected public artists’ work from mutilation or destruction.

Gibbs’ mural had become a prominent piece of public art and her lawsuit drew publicity. Like the 5Pointz muralists, Gibbs argued that her work helped make the neighborhood more attractive to city dwellers and tourists alike, thus making it more valuable to developers. In 2017, the parties settled amicably without disclosing the exact terms of their agreement—but did agree publicly that the painting would be preserved and incorporated into future development.

Of course, it’s already too late for that kind of solution at 5Pointz. But it’s not too late for a settlement. In 2008, Los Angeles muralist Kent Twitchell sued the federal government and others for destruction of an iconic six-story painting on a government-owned property in downtown LA. Although the mural is gone forever, Twitchell got $1.1 million in the settlement. At the very least, that covered buying supplies for his next epic work.