Would you bring a Polish bottle of chardonnay to a dinner party? How about a riesling from Michigan? A bubbly from England? These would be bold choices today, but in a few years, those wines may be as welcome as bottles from France, Italy, or California.

The map of the wine world is undergoing a dramatic change. World wine production is set to fall to its lowest levels in decades, largely due to the weather, according to estimates from the International Organization of Vine and Wine. Meanwhile, wine production in the UK has reached record highs, with sparkling wines leading the way.

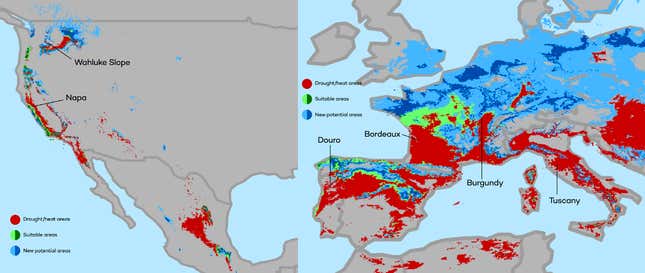

Though experts remain divided on which areas of the world will lose and which will win, they all agree that the world’s most famous wine regions are not going to remain the same. As global average temperatures rise, the best lands to plant a vineyard are moving away from the equator, creeping up into the northern hemisphere and down into the southern hemisphere.

The first comprehensive study on the subject was published in 2013 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. It made the dramatic claim that wine produced in Burgundy, France and Napa Valley, California, among many other regions of the world, will disappear within the next 50 years.

The researchers argued that new wine-growing regions would rise, and produce better wine than the current champions. In Europe, England, Poland, and Austria would develop more favorable conditions, the study predicted. And in the US, the states of Montana, Wyoming, and Michigan would reap benefits.

But the study was criticized (pdf) for its poor methodology. Though these traditional regions are definitely under threat, follow-up studies have painted a more complex picture. As global temperatures rise, local weather changes may play out differently across the world: Some regions will experience droughts, and others floods. A better way to predict these changes is to study individual regions.

A study published earlier this year showed that cava, a type of sparkling wine produced in northern parts of Spain, will taste worse as a result of warmer temperatures. The region is expected to be drier and warmer, leading to earlier ripening of the grape, which would in turn make the wine less acidic and more sugary.

On the other hand, a 2016 study found that climate change has benefited French vineyards since the 1980s. Early ripening has made the grapes richer in tannins, the chemicals that give red wine its color—and can add notes of bitterness and astringency, as well as complexity. But the study warned that these advantages may not last for much longer, as temperatures keep rising.

There is also hope for regions where the climate doesn’t change drastically. A 2015 study suggests that some regions may be able to adapt to the changes in the climate, through the use of methods such as irrigation.

In the worst case, other regions are ready to pick up the slack. You may not be aware that wine is produced in India, China, and Russia. In face of climate change, which region will become the next Bordeaux or Napa? Here are some of the best candidates:

England

Wine produced in England used to be the butt of jokes. No more. Bubbly from Blighty is “truly delicious: creamy, edgy champagne stand-ins,” according to wine columnist Alice Feiring. As the climate has changed, the South Downs region in England has developed weather similar to Champagne region. It happens to already boast the chalky, clay soil that characterizes the iconic part of France. Put them together and you’re likely going to be hearing a lot more about English wines in the coming years.

Michigan

Like Montana, the state of Michigan already produces wine on a small scale. And it’s scaling up as the climate warms. The state’s wine production has been steadily growing, according to Michigan Grape and Wine Industry Council. The number of wineries has gone from 16 to 130 in the last 10 years.

Tasmania

Just as Michigan and Montana might become competitors to California’s Napa Valley, Tasmania threatens Australia’s Barossa Valley. From dry rieslings to sauvignon blancs, travel writer Krisanne Fordham says Tasmania produces wines “vastly different” from what is offer in rest of Australia. Climate change is likely to make the region’s weather even better.