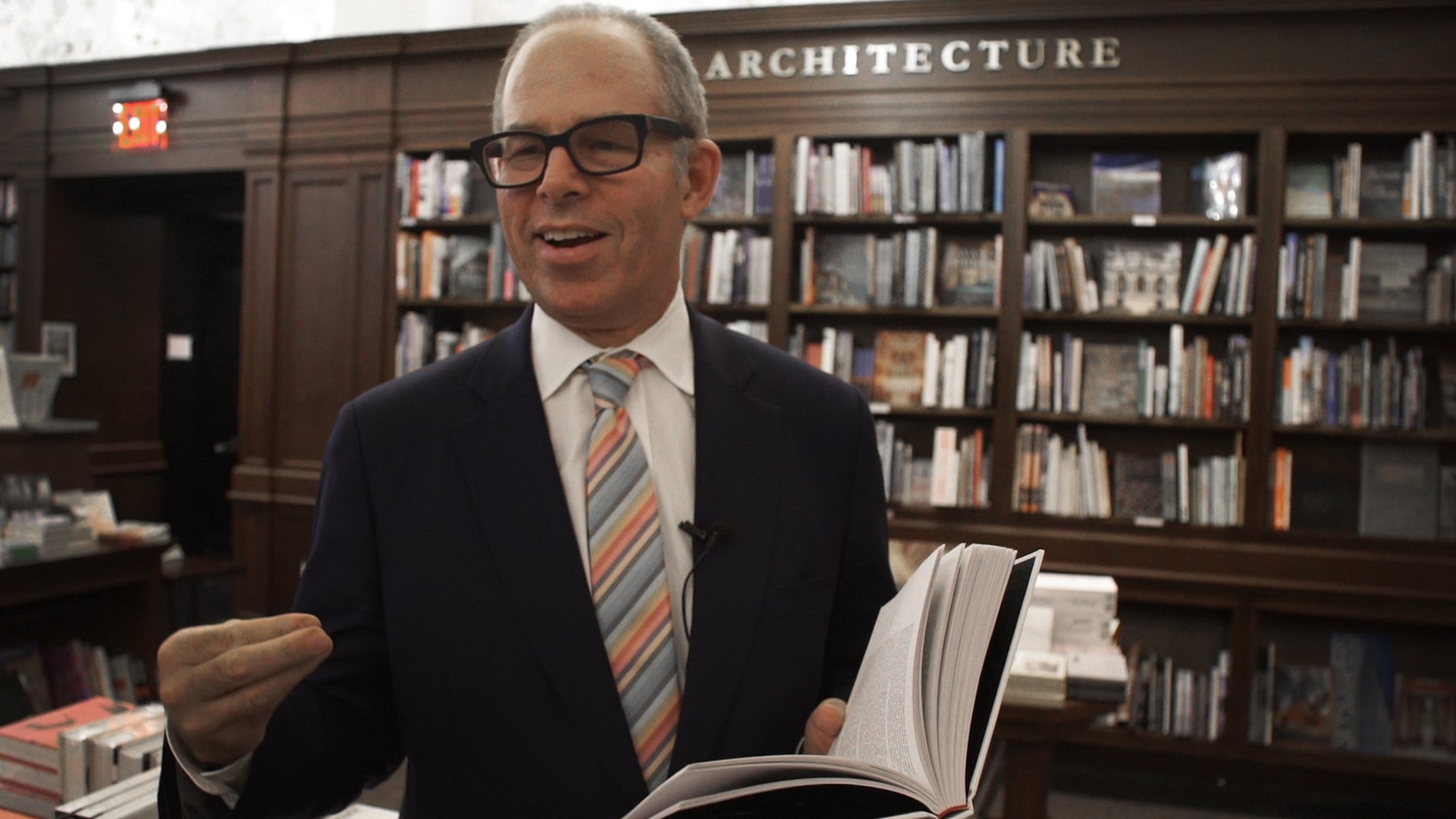

Michael Bierut says never trust a designer who doesn’t like reading

Designers are geniuses at style, but rarely expected to wrestle with the words.

Designers are geniuses at style, but rarely expected to wrestle with the words.

According to graphic design legend Michael Bierut, this long standing cliché about the division of creative labor needs to change. “I’m very suspicious about hiring graphic designers who don’t seem to be enthusiastic about reading,” he says, explaining that he owes his early design education to books he found in the library as a student in Parma, Ohio. Bierut has kept up this reading habit, incorporating reading for pleasure in his busy schedule as a partner at the design consultancy Pentagram.

The author of five books, a lecturer at Yale University and a co-founder of the blog Design Observer, Bierut is also among the most widely read essayists on the topic of design. In his new book, Now You See It and Other Essays on Design, Bierut demonstrates why reading and to some extent, writing, are fundamental habits for creative professionals.

The need to read

A love of reading, Bierut argues, leads to better design.

“Architects work with brick and steel, fashion designers work with fabric, and graphic designers work with letters and words, sentences and paragraphs,” he explains. Bierut observes that designers who don’t read tend to see words like “gray matter to be arranged on a page in an abstract way.”

Bierut’s argument for reading seems simple, yet it’s radical for the profession. Design schools dedicate semesters on finessing styles; many design magazines look like picture-heavy catalogs and many design competitions are still judged based on how something looks. But reading is what leads to meatier, original design content. “There’s nothing wrong with cool stuff, but the most cool looking stuff is not only great visually but informed by the culture,” argues Bierut.

A designer who doesn’t read will have no sympathy for the reader and the author. The telltale signs are all too common: illegible, teeny, tiny fonts, annoying decorative flourishes, confusing information hierarchy, embarrassing typos, or costly gaffes that can cause a PR nightmare for their client. Conceivably, the designers of Nike’s Air Bakin’ trainers could have avoided angering the Council on American-Islamic Relations if they had bothered to check if the flame design they came up with didn’t actually read “Allah” in Arabic script. Similarly, many lives could be improved if graphic designers bothered to learn about the tenets of health literacy so they can do a better job presenting pertinent health information to overwhelmed patients.

In the book’s title essay, “Now You See It,” Bierut expounds on why designers need to take the trouble to pore over texts they’re given, even if the design solution seems obvious at first glance. Citing a 1990 Stanford University dissertation with the alluring title, Overconfidence in the Communication of Intent: Heard and Unheard Melodies, Bierut explains the “curse of knowledge” that results in boring designs or knock-off solutions.

In the interest of efficiency, designers tend to go straight to the drawing board—firing up design software, flowing in text, or sketching on their tablets—instead of considering if their solution will resonate with their readers. “If you already know the answer, you tend to underestimate the difficulty of the question,” says Bierut. Reading and research are often the crucial initial steps missing in the design process.

Books, blogs and beyond

An avid reader of biographies, novels, history and magazines, Bierut adds that reading about unrelated topics helps designers—and arguably all creative people—land on novel ideas.

“Every good writer will throw in a reference to something that you weren’t there for. If you’re smart, that’s your lifeline to your next thing. Let others infect you with their enthusiasm for hopping between other subjects—for thinking synthetically about disparate things,” he says.

His favorite books are not design books: Act One by Moss Hart for instance is a memoir by an American playwright. (“It’s my favorite book about the creative process, and no one has heard of it…anyone who does any kind of creative work will relate to this,” gushes Bierut.) Or Nicholson Baker’s novella about a man buying shoelaces, The Mezzanine. (“There’s something about his attention to detail that’s so appealing!”)

In Now You See It, Bierut displays his polyamorous curiosity and facility for explaining the world through a designer’s lens. With his trademark wit and penchant for charming folksy anecdotes, he hops from an essay about the architecture of his childhood home, to several entries about his philosophy on fonts, detours to discussing dalliances with clients and concludes with reflections about his most-discussed work: the Hillary Clinton campaign logo. In each of the book’s 53 bite-sized chapters, Bierut demonstrates how a designer can go into one rabbit hole and emerge smarter by taking the time to reflect about the visuals he encounters or produces.

“Each of us live in a world that’s inundated with misinformation, half-truths and fake news so much of it in beautifully packaged and beguilingly delivered,” he writes in the book’s introduction. “Thinking hard about the forms that ideas take may be the most important kind of thinking of all.”