Beyond the globally familiar sari or tandoor oven, there’s a whole world of Indian design that is rarely recognised.

From the dabba (a stacked lunchbox) to the jhola (a cloth bag) to Mysore sandalwood soap, this design often takes the form of beloved everyday objects that can be found in households or on the street across the country. Many of these items, such as the terracotta matka (pot), have been part of local traditions for centuries. Others, like the pressure cooker, were imported decades ago, but have evolved to occupy a special place in Indian culture.

Now, 100 of these definitive Indian objects are the subject of a new book titled Pukka Indian by Jahnvi Lakhóta Nandan, published by Roli Books.

For Nandan, a perfumer by training who also holds a PhD in architecture, the goal was to highlight the uniqueness of Indian design, which has evolved with a focus on affordability and thrived in an atmosphere of relative scarcity. It took a year to shortlist the 100 objects, which range from household items such as agarbatti (incense sticks) to street sights like the Z-shaped petrol pump, designed by Larsen & Toubro in 1991.

“Most of these objects are used around the country and transcend socio-economic classes,” she told Quartz, adding that they have all gone on to define specific habits of lifestyle in India.

In her book, Nandan digs into the history of each of these objects, some of which date back to the Indus Valley Civilisation but continue to be used today. She also traces the influence of political events such as the Independence movement, which prompted the rise of indigenous advertising and packaging design.

Here are the stories of 10 of the objects featured in the book, alongside photographs taken by Shivani Gupta, excerpted with permission from Roli Books:

Hindustan Ambassador

Date of origin: 1958

Material: Metal, rubber, plastic

“Manufactured by Hindustan Motors, it was the first indigenously-produced car to hit the roads in 1957. At that time the Indian government had banned the import of cars. So the Ambassador acquired supremacy over Indian roads at a time when socialist India was starved of cars. The first elections in independent India concluded in 1952. The government ordered and continued to order close to one-fourth of the company’s production. There were only three models available until the Japanese came in with the urbane 800cc Maruti Suzuki in 1983. So for over three decades it was only the ‘Amby’ that was the preferred mode of transport for all those who could afford a car, as it was considered to be both efficient and an all-terrain vehicle. Such was its popularity that till 2002 it included amongst its users the prime minister of India.

[…]

However, with liberalisation many international carmakers entered the country in the 1990s—in the heydays of the Ambassador’s popularity, India boasted only three car manufacturers, but now there were over 30. After four decades of rule over the Indian roads, this influx of newer, cheaper cars has substantially dented the Amby’s popularity, but not quite ended it, as 33,000 Ambassador taxis in Calcutta (Kolkata) alone continue to ply. To its users, the car does not represent technology but familiarity, safety and roominess. In May 2014, the production of India’s first car stopped after 71 years of history.”

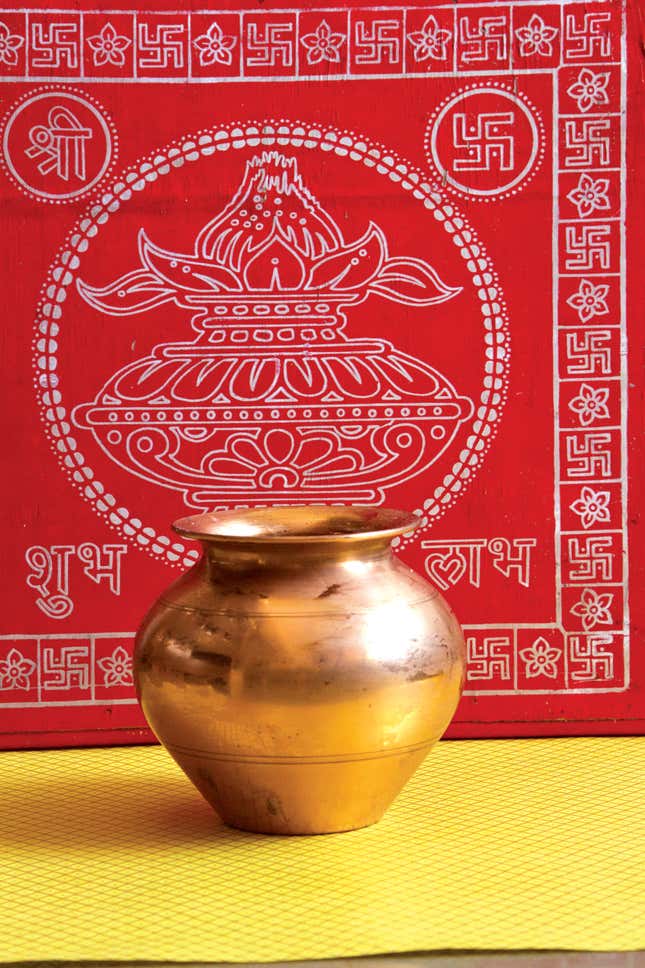

Lota

Date of origin: 2300 BCE, Daimabad

Material: Metals, plastic, clay

“The use of lota (a word with no English equivalent) has been epic. A shapely spherical object, its scooped neck makes it easy to hold between fingers. Traditionally made of copper or brass, possessing an orange hue to a bright yellow or a subdued golden patina, the lota dazzles and makes all Indian kitchens glow. A multipurpose metal vessel for all walks of Indian life, it is used for fetching water, performing religious rituals, and even practising yoga.

It functions as a tumbler, water container, canister, jug, and a stackable container, all in one. Indian consumer fetishism combined with Brahmanical puritanism ensures that individual lotas are used for distinct purposes even if identical; this results in an attractive array of lotas in most homes: a large one for storing water; a smaller one for bathing; or, a miniature lota for the home shrine that stores sacred water from the river Ganges. The lota is an undisputed tribute to its unknown creator.”

Sari

Date of Origin: Late 19th century, Calcutta, now Kolkata

Material: Cotton, silk, chiffon, other fabrics

“A 108 variations of the sari drape have been identified, varying from region to region, such as in Maharashtra where it was tucked between the legs making it easier for women to work in the fields or in Coorg where wearing the pleats at the back freed the gait compared to a more rigid drape without a pleat. Despite the variations, modern India chose to follow a unified style that was propagated by the vibrant Tagore-led intelligentsia in Bengal in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, who in turn borrowed it from the cosmopolitan Parsis

of Bombay (Mumbai).

At that time Victorian conservatism considered a sari with an almost bare torso unacceptable in public. So a blouse and a petticoat were added to cover the bust and hide the legs. This period saw intense social changes, and many women started experimenting, travelling, and assimilating drapes from around the country. So the most convenient way became the way it is worn today, a sari with a fall stitched in for strength, a petticoat for the skirt, and a blouse as a top. This became respectable outdoor wear, as stitched clothes are structured to mimic the body whereas the sari adapts to it.”

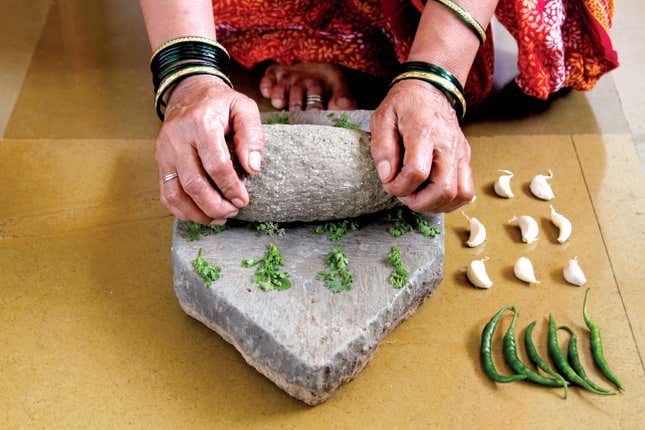

Sil Batta

Date of Origin: Unknown

Material: Stone

“The origin of sil battas can be traced to the Tittiriya Samhita, a guide to rituals written during the Vedic period. It lists 10 objects that an Indian kitchen must have. This includes a large stone slab called drasad used to crush or grind the soma creeper with the help of a smaller stone called upala placed on the drasad. In a history of over three and a half millennia the sil batta has been used continuously almost every day.

The heaviness of the bottom slab makes it immobile while the top slab shaped like a brick, just large enough to clutch in the palm of both the hands, serves as the weight. The mortar and pestle and the sil batta, however, are two different objects. The sil batta pulverises to a fine paste using flicks of the hand. The movement of the hand is straight rather than circular as in the mortar and pestle so the surface area for grinding is larger. This is also a practical solution to a mortar and pestle because it is flat and can be neatly put away after use.”

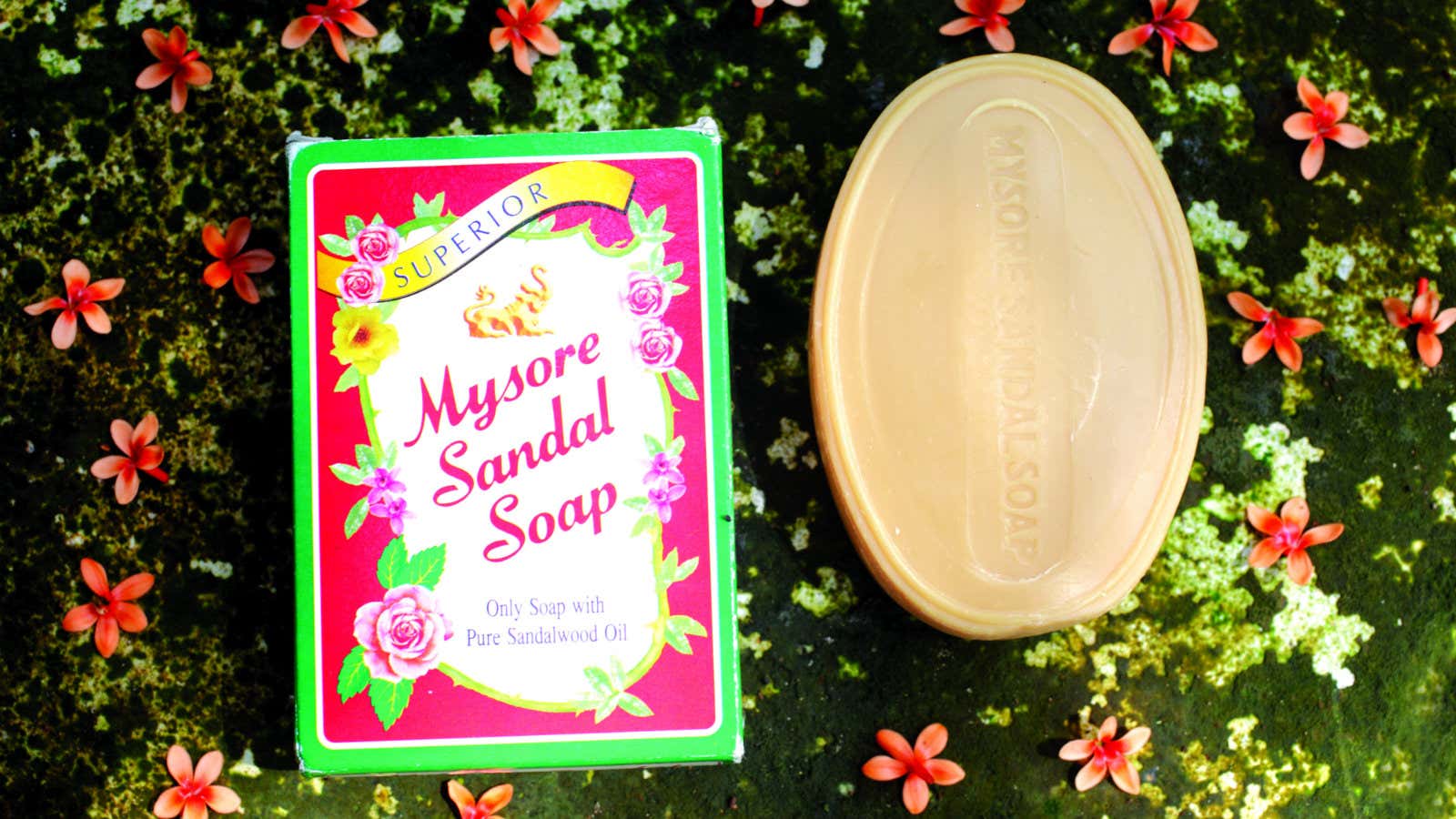

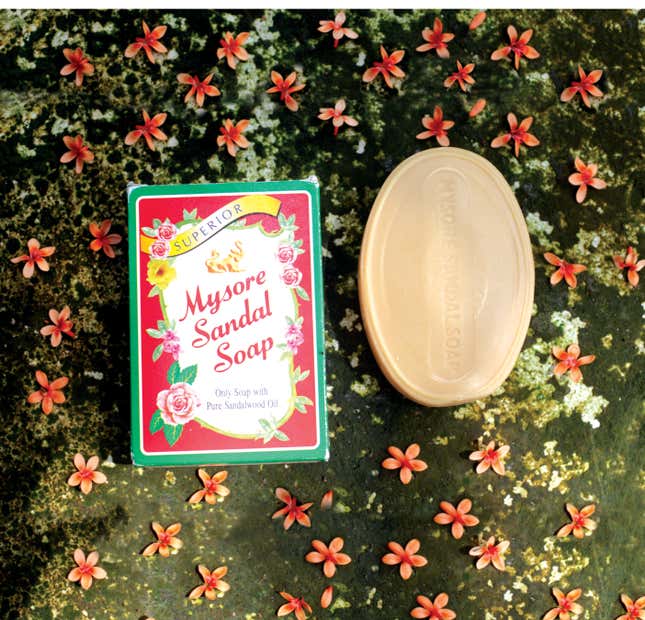

Mysore Sandal Soap

Date of Origin: 1916, Mysore

Material: Natural and identical sandalwood, lactones, soap base

“Amongst the 450 tonnes of soap manufactured every year in India, the most distinguished is the Mysore sandal soap. The soap has a unique warm, milky aroma. It is made from oil extracted from sandalwood trees and is the world’s only sandalwood soap.

[…]

At the turn of the 19th century, Mysore produced an excess of sandalwood. Buying manufactured soap was just becoming fashionable, so King Nalvadi Krishnaraja Wodeyar, the Maharaja of Mysore, ingeniously decided to use sandalwood in soaps. In 1916 he established a government soap factory.

Mysore Sandal Soap instantly appealed to the Indian upper classes as the most fragrant soap in the market, even though it was first sold in the form of cakes without packaging. Later, in the 1960s, a butter-paper packaging (with the mythological animal Sharabha, a creature with the body of a lion and the head of an elephant on it) was adopted. This unmistakable green and red packaging continues to this day.”

Jhola

Date of Origin: Unknown

Material: Cloth, thread

“The jhola is a smart collapsible bag made of cloth. Lightweight, and designed to carry everything from books and pens to fruits and vegetables, its versatility has made it a favourite not only in India but also worldwide where it

serves as the humble forefather of the now ubiquitous and fashionable tote bag. The etymology of the word jhola connotes an action of ‘swinging’ like a cradle. In some languages it refers to a fakir’s bag, a nest of eggs or a feeding bag for cattle and a man’s testicles.

The single strap jhola was an activist’s accessory made famous by participants in the freedom struggle. Mahatma Gandhi carried all his belongings in two of them that he slung across in a neat cross from both shoulders on his bare chest during the 23 day and 300 kilometre Salt March from Ahmedabad to Dandi. Since then journalists, social activists, scholars, and pundits have carried jhola bags. Jholas, thus, carried with them a message of resistance.”

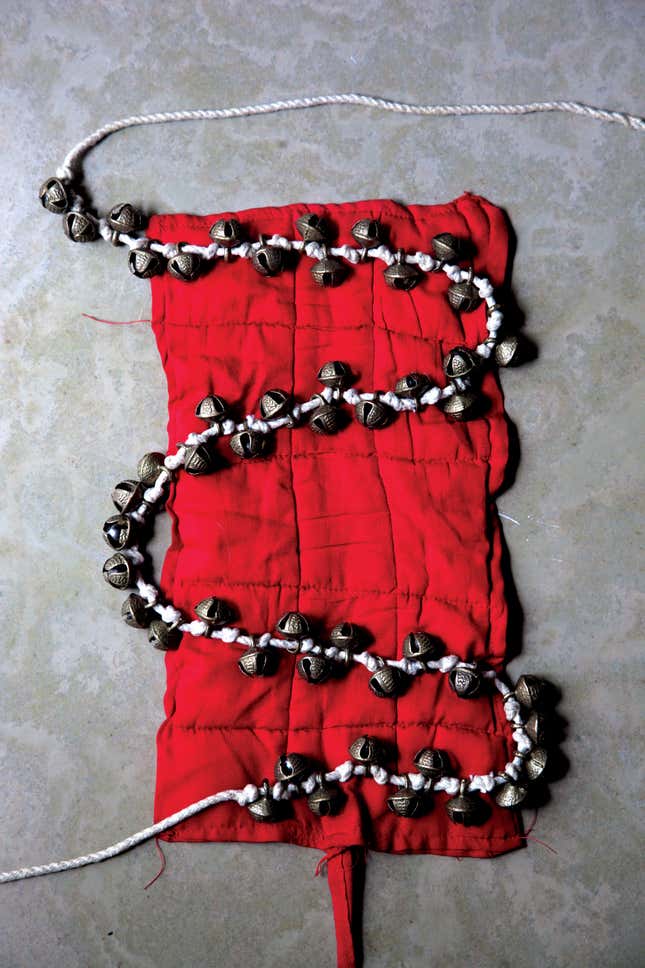

Ghungroo

Date of Origin: 500 BCE–500 CE

Material: Brass bells, leather, cotton string

“This unisex dancer’s accessory looks equally comely on both a man and a woman, and becomes the heart of every beat of the foot; what would have otherwise been just a flat thump on the floor is transformed into a reverberating melody.

[…]

In its simplest initial version, the anklet was just a large metal ring. They became more elaborate as chains or tubes in varying thicknesses depending on the region, style and occasion. In southern India this is called a toda and is made by lacing several silver or gold wires into a coil that rests around the ankle. When bells are attached to them for sound, they adopt onomatopoeic names like kinkini and jhanjhan. In fact kinkini could also refer to the sound from the waist. The bells are set on bands made variously of velvet cloth, leather or simply cotton chord.”

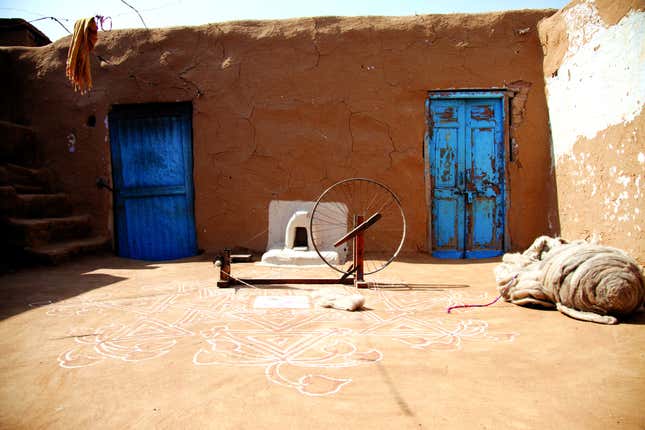

Charkha

Date of Origin: 500–1000 CE

Material: Wood

“Factory-made cloth that resulted in weavers going bankrupt in the early 20th century made the symbol of hand-made cotton thread and the charkha one of the most iconic objects of modern India. The figure of a person spinning a charkha became a matter of national identity and in 1931 when India adopted its first flag—a charkha was placed at its centre.

[…]

For centuries, spinning as an activity had united the country, transcending regional, caste, class, language, and religious diversities as most homes in India used to practise spinning. The charkha also became a symbol of economic independence. It was in the 1920s that Mahatma Gandhi and other members of the Indian nationalist movement adopted this symbol: spinning on charkhas became a practice to assert the desire for self-rule.”

Auto rickshaw meter

Date of Origin: 1977

Material: Metal

“Till the electronic meters came in the 1980s, mechanical fare meters such as those used in the auto-rickshaws or taxis in Delhi were common worldwide for around a century. They consisted of two parts, a mechanical meter that measured the distance and displayed the rate and a flag that put the meter in motion (with a clockwise flick of the flag the auto-rickshaw drivers in India indicate the start of the meter). The flag also signified that the auto rickshaw was on hire. When, in the rest of the world, fare meters became electronic, to make them tamper proof they were moved inside the cab onto the vehicle’s dashboard; it made sense then to drop the flag. But not in India. There were many barriers to adopt the electronic fare meter without the flag, the first of which was its expensive technology. So, India is the only country where the flag carries on, but with modifications.”

Kulhad

Date of Origin: 2600 BCE, Indus valley

Material: Earthen clay

“Kulhad cups are the simplest form of pottery that can be ‘thrown’ on a potter’s wheel. The only raw material required is the sediment deposited at the bottom of the river bed. Removing the sediment prevents the river from flooding. Clay is prepared from this sediment by extracting excess water and course debris. The potter places a lump of this clay on the wheel and deftly moulds it by applying pressure with his fingers. The cup shape is then neatly sliced off the wheel and laid out to dry in the sun. This dry, ash-coloured, raw form with a smooth wall is placed in the community kiln that is fuelled by straw or cow dung sourced from nearby farmers. Once firmly baked, washing off the ash and grime of the kiln reveals the rich orange hue of a good kulhad.

[…]

For the potters who make kulhads, chaiwalas on the dense Indian Railways network are their biggest clients, as the latter have been serving passengers onboard since the first train services started in India in the mid-19th century.”

Excerpted with the permission of Roli Books from Pukka Indian 100 Objects that Define India by Jahnvi Lakhóta Nandan.