The Narendra Modi government has unveiled a grand plan to lead India’s banking sector out of its acute toxic-loan mess.

Public sector banks, which command a lion’s share of the loans and deposits in the Indian banking system, will receive Rs2.11 lakh crore ($32.43 billion) over the next two years to improve their capital position. Out of this, Rs1.35 lakh crore will be provided through recapitalisation bonds—government instruments subscribed to by banks. The remaining Rs76,000 crore will either be provided by the government, or the banks will tap the financial markets.

The move could provide respite to a sector whose total gross non-performing assets (NPAs) in March 2017 stood at about Rs7.29 lakh crore, equivalent to 5% of the country’s GDP. NPAs are loans on which borrowers have stopped repaying either the principal or the interest. These toxic loans have put banks’ balance sheets under pressure as they need to make higher provisions to cover for possible defaults. In all, public sector lenders needed between Rs1.4 lakh crore and Rs1.7 lakh crore by March 31, 2019, to meet regulatory requirements for their capital positions, according to a report by rating agency CRISIL.

As the banks have been busy cleaning up their books and strengthening their balance sheets, they have been restrictive with lending in an environment where the demand for funds is already subdued. As a result, loan growth at the end of March 2017 stood at 5.8%, the lowest since 1994-95.

With this upcoming round of capital infusion, the government now expects banks to fix their balance sheets and begin lending aggressively once again, eventually kickstarting the economy.

However, the devil will lie in the detail.

Is it enough?

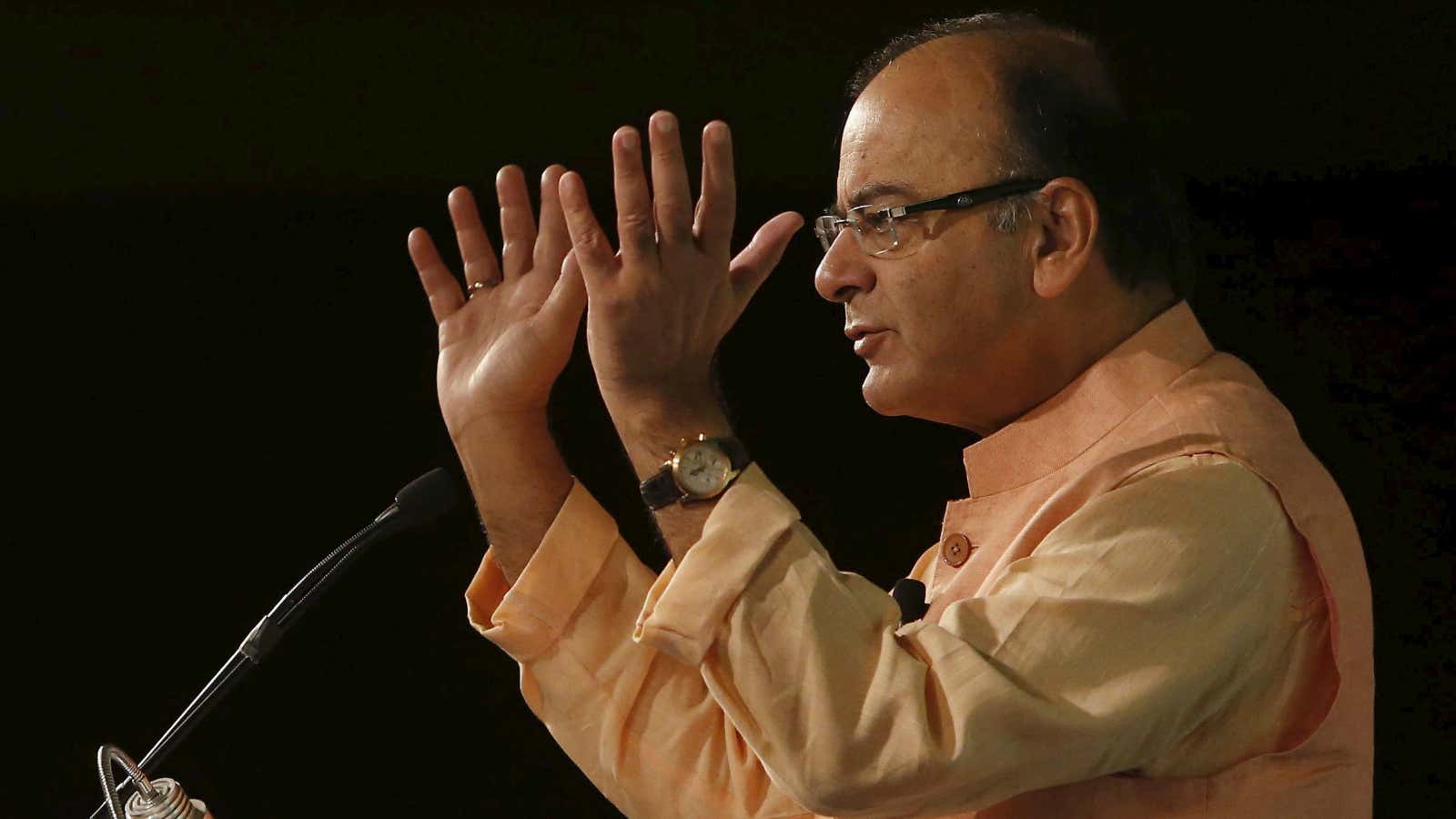

At a press conference in New Delhi on Oct. 24, following the announcement of the bank recapitalisation plan, finance minister Arun Jaitley gave out few details, including those of the recapitalisation bonds.

Apart from questions like who exactly will issues the bonds (the government itself or an institution like the Life Insurance Corporation of India), there is concern over how this will impact India’s fiscal deficit. In the last three years, the government has managed to bring down the fiscal deficit—a situation when expenditure exceeds revenues—from 4.5% of GDP in 2013-14 to 3.5% of GDP in 2016-17. Now, the government has laid out plans to reduce the deficit to 3.2% of GDP for this financial year.

However, since the government is already in a deficit situation, doling out more than Rs2 lakh crore over the next two years and ensuring that it doesn’t breach its deficit target may be a challenge. And, therefore, it is likely that these recapitalisation bonds may well have an impact on the country’s already stretched balance sheet.

Also, the government hasn’t publicly identified which banks would receive the funds. “There will be a differential approach; it will factor in the size, culture, ethos, and the prudence that the banks follow in their banking, and all of this will be announced in due course,” said Rajiv Kumar, secretary at the finance ministry’s department of financial services, without giving out any other details.

Meanwhile, Jaitley explicitly mentioned that this proposed capital infusion would be accompanied by banking reforms. But again, there are no details. This is critical because the government has stepped in more than once to rescue ailing public sector banks. In the 1990s, for instance, recapitalisation bonds were issued to helps them tide over a bad-loan mess. So, any funds given out must be closely monitored under stricter guidelines to avoid frequent capital infusion.

“There are some deep-seated issues (management and governance) in the banking system that need to be sorted out. If that is not done, then this capitalisation plan can save the bank for the time-being but the problems may emerge again,” said a former public sector banker, requesting anonymity. “Therefore, the emphasis needs to be on the reform plans.”