A culturally insensitive nursing textbook illustrates the pickle medicine is in

In an ever-evolving culturally diverse society, efforts to be sensitive can often have the opposite effect. The recent scandal over a textbook for American nurses is a prime example of this. Nursing: A Concept-Based Approach to Learning was supposed to teach nurses to relate to patients of various backgrounds. The result, instead, was incredibly tone-deaf and offensive.

In an ever-evolving culturally diverse society, efforts to be sensitive can often have the opposite effect. The recent scandal over a textbook for American nurses is a prime example of this. Nursing: A Concept-Based Approach to Learning was supposed to teach nurses to relate to patients of various backgrounds. The result, instead, was incredibly tone-deaf and offensive.

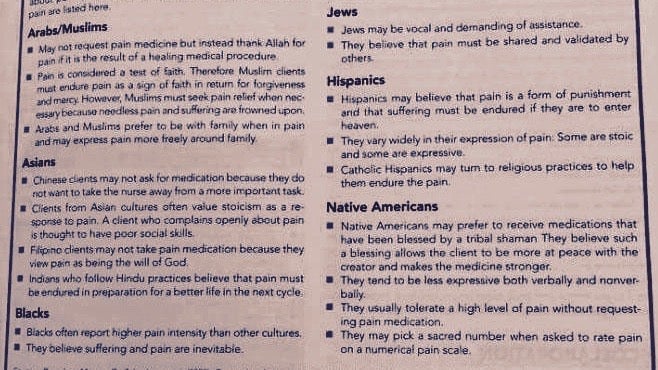

Pearson Education, the publisher at the center of this scandal, was presumably trying to do a good thing when it printed its unseemly list of generalizations about Arabs, Asians, Blacks, Jews, Hispanics, Native Americans, and Muslims. But the road to hell is famously paved with good intentions, and this pithy list, in a section titled “Focus on Diversity: Cultural Differences in Response to Pain,” is no exception.

It provides, for example, that in a hospital setting, “Jews may be vocal and demanding of assistance” because “they believe that pain must be validated and shared by others.” That is news to this Jew, who—based on the book—treats pain with the stoicism of an Asian, because I “believe suffering and pain are inevitable,” which is apparently a characteristic of black patients.

Onyx Moore, a “wellness advocate” in Los Angeles, California, posted the offending page on Facebook on Oct. 16, noting, “This is an excellent example of how not to be even remotely culturally sensitive.”

It took off on social media and by Oct. 19 the publisher had issued an apology. Pearson’s global product development chief Tim Bozik explained in a YouTube video that “in an attempt to help nursing students think through the many facets of caring for patients, we’ve reinforced a number of stereotypes about ethnic and religious groups. It was wrong.”

Now schooled, Bozik says the company is reviewing all educational materials and has already changed electronic versions of the offending textbook. “Educating students, particularly those who will be our next generation of caregivers, is a profound responsibility,” Pearson Education notes in text accompanying this video. “The material included in these texts does not reflect our values as a company and how we want to serve students.”

Moving on

Apologizing, though awkward, is actually a lot easier than figuring out how to address cultural sensitivity in a non-offensive way. In the field of medicine, where ethnicity influences health risks and medication effectiveness, for example, professionals can’t be blind to differences.

Doctors argue that “race matters in medicine.” Take an anti-platelet drug Plavix (clopidogrel), say, which is activated by a particular gene variant that many Asians and Pacific Islanders don’t have. The drugmaker Bristol Meyers Squibb aggressively marketed the drug in Hawaii and Plavix “became the drug du jour in Hawaii if you had a heart attack,” says Esteban Gonzalez Burchard, a physician and professor at the University of California San Francisco. “What they overlooked is that most of Hawaii is Asian or Pacific Islanders.”

The US National Institutes of Health also acknowledges that ethnicity influences disease. Certain genetic conditions are more common in particular ethnic groups, like sickle cell disease, which predominantly afflicts people of African, African American, or Mediterranean heritage; and Tay-Sachs disease, which most often occurs among Ashkenazi Jews of eastern and central European descent, and French Canadians.

But obviously resorting to broad generalizations only offends and ends up exacerbating rifts. Doctors may agree racial and ethnic identities matter in medicine but they can’t agree on how to present that. Some want to see race and biology placed in a wider social context so that medical practitioners will be more effective. In a 2016 article in Academic Medicine, researchers wrote of medical education, “current preclinical medical curricula inaccurately employ race as a definitive medical category without context, which may perpetuate misunderstanding of race as a bioscientific datum, increase bias among student-doctors, and ultimately contribute to worse patient outcomes.”

Our biological, ethnic, and social identities are also rapidly changing. The more globalized and diverse we become as a society, and the more people mix, the less a one-shoe-fits-all approach will work when it comes to medicine or anything else. Many people aren’t just one race or ethnicity anyway, and we don’t know much about each other just by looking, or based on broad assumptions. Our interactions and our families are now far too complex for simple categories and boilerplate statements.

This leaves Pearson Education, and medicine at large, in a pickle—one that reflects society more broadly. We can’t ignore the way culture, race, identity, and ethnicity influence people’s health and experiences if we hope to understand one another and treat each other appropriately, respectfully, and equally. But we also can’t ignore the fact that each of us is also a unique individual, not just a prisoner of biology or any one culture.

No one, not the publisher or the rest of us, can hope to solve these tricky issues perfectly, once and for all. While future editions of nursing textbooks may shirk the formulations that led to this firestorm, in an evolving society with a shifting consciousness, even the most illuminated among us will inevitably seem backward eventually. If there’s one generalization that is safe to make, it’s that times change, and so do our ideas about what’s right.