How writers make believable characters, according to the creator of Mad Men

In the sixth season of Mad Men, Nikki is on-screen for less than two minutes. In that time, we learn that she is a smug engaged person who disapproves of the white ad lunatics who employ her friend, Dawn, who she thinks is too subservient.

In the sixth season of Mad Men, Nikki is on-screen for less than two minutes. In that time, we learn that she is a smug engaged person who disapproves of the white ad lunatics who employ her friend, Dawn, who she thinks is too subservient.

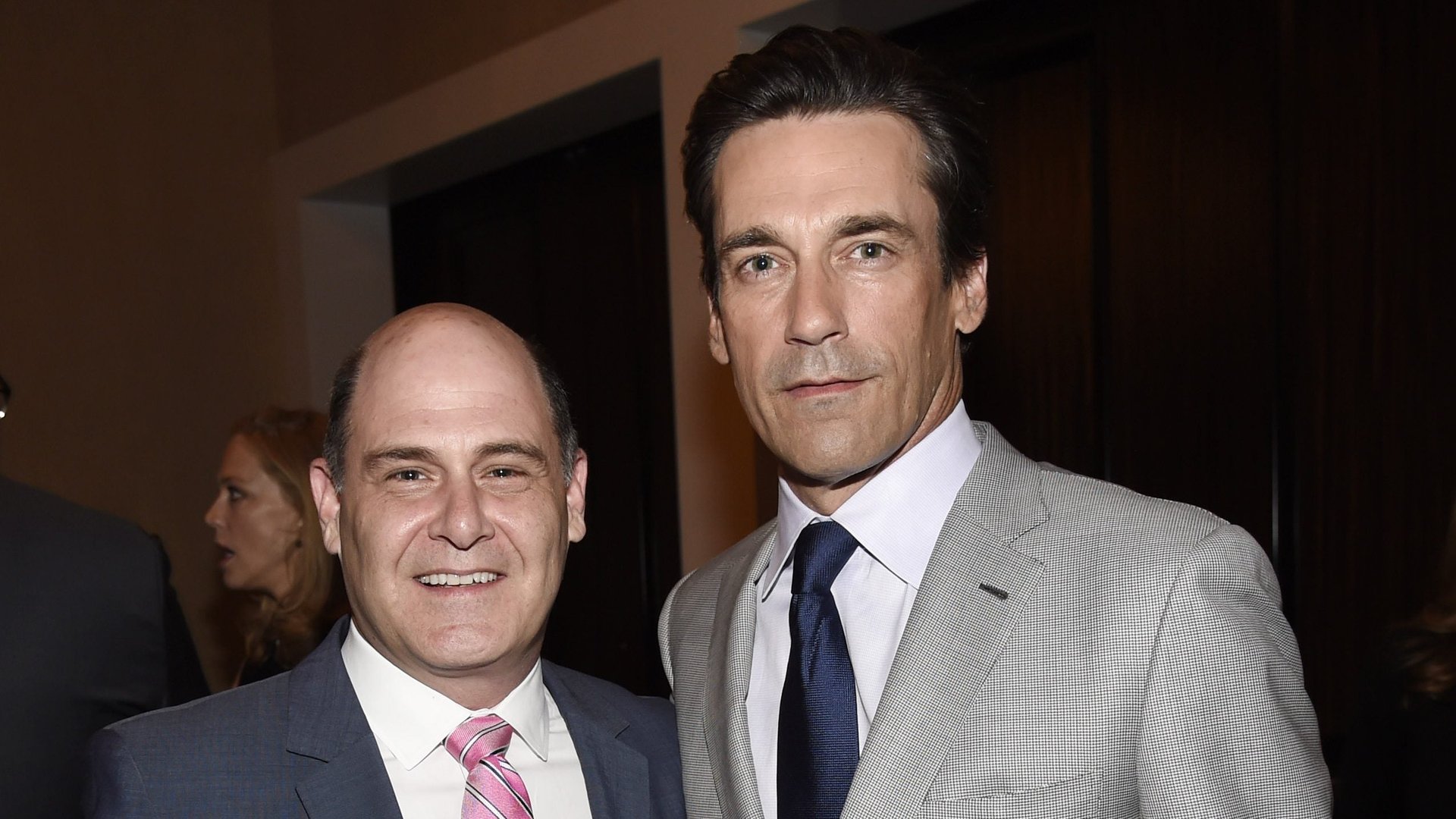

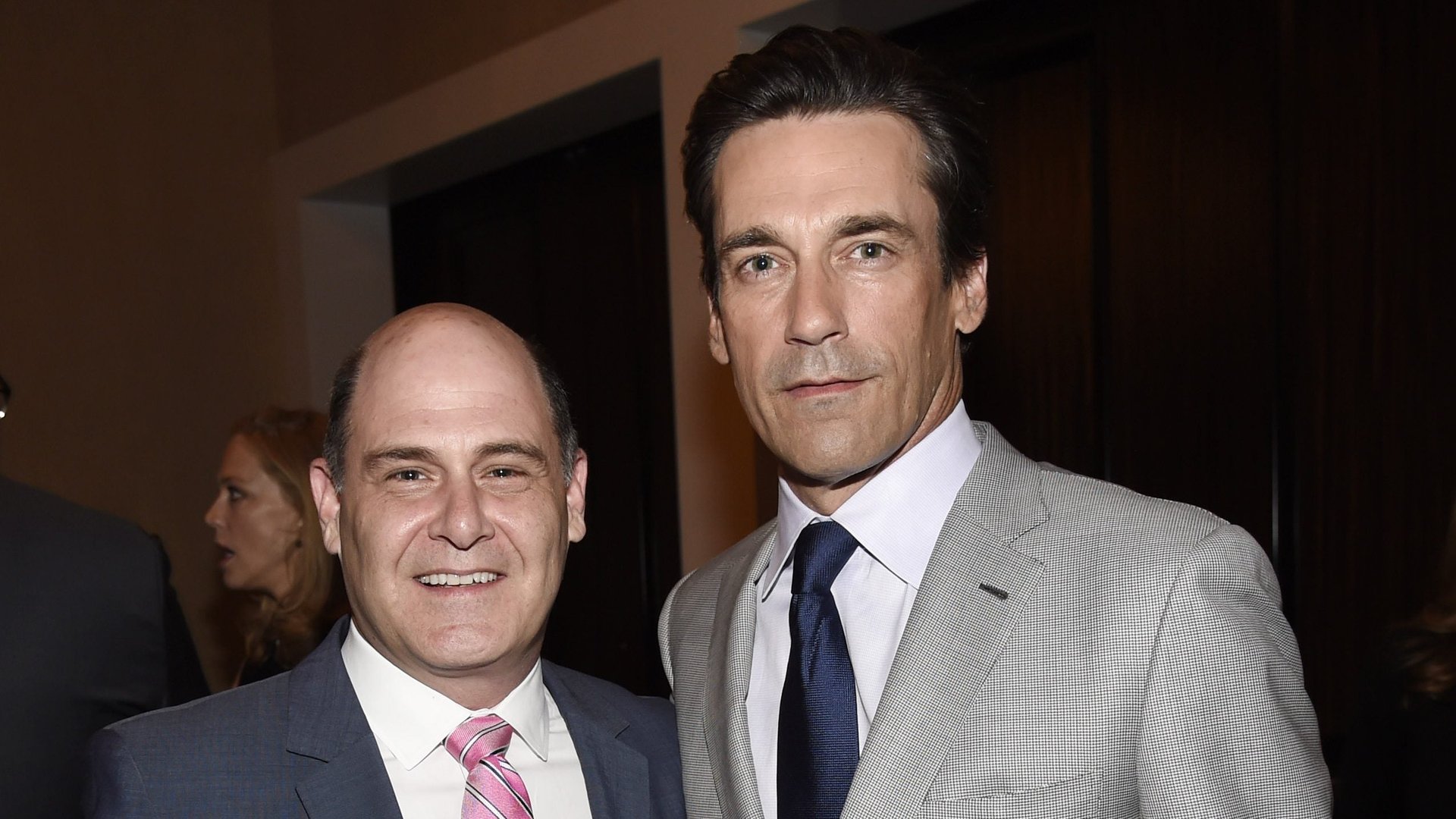

It’s not an Emmy-winning monologue, but the small moment demonstrates a bedrock of good TV and film writing. Last night at 92Y in Manhattan, Mad Men show runner Matthew Weiner, in conversation with White Teeth author, Zadie Smith, explained that the key to a full character is that she thinks she’s a star.

At the event, in which Weiner promoted his novel, Heather, the Totality, out yesterday from Little, Brown, someone from the audience asked how he creates such varied characters. “Every character has an ego,” said Weiner. “Every character has an agenda.”

It’s an old adage of acting, that there are no small parts, only small actors, but it seems easier said than done to bring those roles to screenwriting. Consider the Oscar-winning La La Land, in which three entire characters function only to tell Mia, Emma Stone’s character, to go to a party, or the gaggle of basketball or poker-playing men in rom-coms like Made of Honor, who exist solely to list pros and cons of the scheme for the female love interest.

In contrast, Mad Men, which ended in 2015 after seven seasons, is full of tiny roles written for characters we imagine will leave the screen, and then go on with a busy schedule or depressive line of thinking: A Heinz oven-baked beans executive who’s desperate to be cool and forget the war, or the secretary of four episodes who, on her first day, gets a coffee and a tea for her boss and says, hopefully, “I’ll just have whichever one you don’t want.”

Nikki, waiting for a late Dawn to arrive after work, is indeed just a basic “best friend” character, whose role is to highlight Dawn’s guilt and anxiety at work. But she has an entire lecture written on her face before she ever speaks, and her own married future to reconcile with.

Smith agreed, saying that her writing students create characters that are “kinds” of people, like “the kind of person” who plays tennis or wakes up early, people whose personalities are just a string of interests and activities. Instead, she suggests, what the viewer or readers sees should be just the tip of the iceberg of a character. That’s the approach that makes shows like Broad City work—the audience imagines that if we didn’t peep into the show, the central characters would go on, making up jokes for the sake of their own amusement.