One of Qatar’s royals says fake news started the Iraq War and the gulf blockade against her country

Doha, Qatar

Doha, Qatar

“Fake news” is a neologism that grew to prominence during the 2016 US presidential election, thanks to Donald Trump. But while fabricated news and the spread of misinformation seems like a largely recent phenomena, it is a problem that has led to political instability, war, and even the destruction of education in those affected countries.

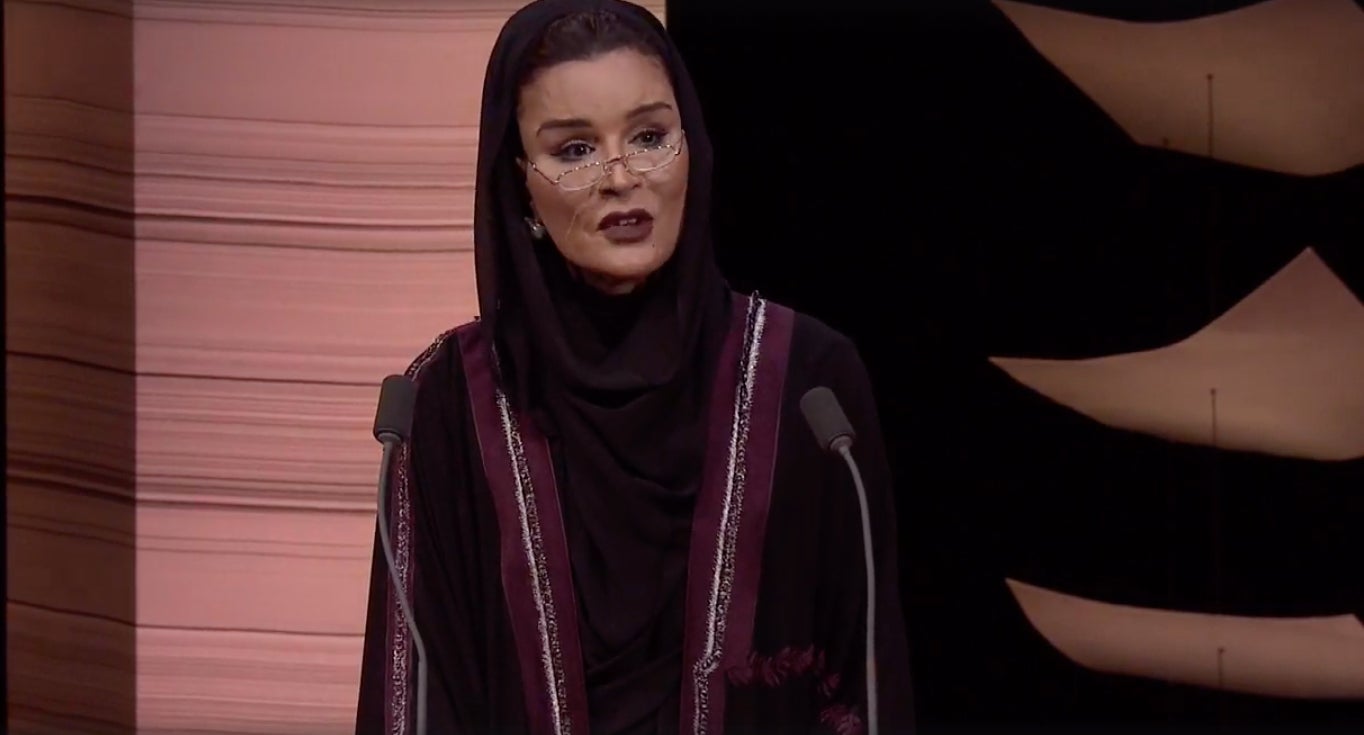

That’s according to Qatar’s Sheikha Moza bint Nasser al-Missned, known as the “matriarch of the modern Gulf” (paywall), in a speech on Nov. 15 at WISE 2017’s summit for education. She made the case for how fake news has been a problem for quite some time and has specifically led to the Iraq War, which lawmakers gave the green light on, based on information that transpired to not be true:

Iraq was besieged for 13 years using tools of deception, and excuses were fabricated to justify invasion in 2003. It was so strange that the invasion was dubbed as liberation. Instead of finding weapons of mass destruction, Iraq saw massive destruction. Iraq’s education system, one of the best in the region in 1990, was in complete ruins. A country that was on the verge of eradicating illiteracy, was caught in the midst of wars and conflicts that dragged progress back to the unfortunate conditions of the past.

With those same tools, Yemen is besieged today, so that it may not know prosperity or stability. So that it drowns in a dreaded triangle of ignorance, disease and illiteracy.

With those same tools, a blockade is imposed on Qatar since the 5th of June. Some wanted to make matters difficult for us, yet it was only difficult for them. They wanted us to change, yet we remain unchanged.

A world that is congested with fake news should not stop us, as advocates of education, from standing on the side of truth. We must keep faith that an education grounded in values will instill the importance for truth to take precedence over personal beliefs in educational contexts.

Sheika Moza is chairperson of Qatar Foundation for Education, Science and Community Development. She’s launched a campaign to get 10 million children into schools around the world.

Her pointed remarks on the blockade echo what Qatar’s emir, Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al-Thani’s said on Nov. 14:

The negative impacts of the blockade were temporary and our economy has managed to contain most of them very quickly, while adapting and developing itself in the course of the crisis management.

But they could have a point. As Quartz previously reported, the blockade may have begun with a hack that created a slew of fake news. The spread of misinformation is increasingly becoming a problem politically, around the world. New data suggests that fake news was nearly as ubiquitous as credible news on the platform in the days immediately before and after the US presidential election in 2016.

In May, Russian hacks attempting to spread misinformation failed to bring down Emmanuel Macron in France’s presidential election. And ahead of the German elections this year, Angela Merkel’s coalition passed a law fining social media networks up to $50 million for not removing posts that spread hate speech and propaganda.

Meanwhile, this past week in Somaliland, the self-declared republic in northwestern Somalia, the electoral commission blamed what it called “external forces” for spreading “inciteful and tribalistic” information (in Somali) and decried its inability to control the proliferation of these messages.