Elephants are autonomous and conscious, and deserve their day in court

“Legal personhood” is not as straightforward as it sounds. For example, in the US, corporations are considered “legal people” in certain contexts because it’s recognized that an entity can also be a “person.” Now, the Nonhuman Rights Project is suing on behalf of three elephants in the Commerford Zoo in Connecticut, claiming that they, too, are “legal people.”

“Legal personhood” is not as straightforward as it sounds. For example, in the US, corporations are considered “legal people” in certain contexts because it’s recognized that an entity can also be a “person.” Now, the Nonhuman Rights Project is suing on behalf of three elephants in the Commerford Zoo in Connecticut, claiming that they, too, are “legal people.”

The Nov. 13 lawsuit, filed in state court, argues that a “person” is not a “human being” but an “entity with the capacity for legal rights.” As such, captive elephants Beulah, Minnie, and Karen are “persons within the meaning of Connecticut law” and so entitled to a hearing on the basis of a writ to “bring the body,” known in legal parlance as a petition for habeas corpus.

This type of petition is brought by someone—usually a human being—claiming unlawful detention. In this case, an animal-rights advocacy organization is arguing that the three elephants, who range in age from 45 to 50 years old, are “persons” being held unlawfully against their will, in harsh conditions, each after a lifetime of servitude, and should be released to a sanctuary.

It’s a creative argument, and one that might not succeed. The same advocacy group attempted similar litigation on behalf of chimpanzees in New York and failed. But it isn’t a crazy argument to make: claims that have seemed absurd to a culture at one point—like the right to equal protection under the law for all people regardless of race or gender, or the right to marriage regardless of sexual preference—become commonplace decades later. This is how rights are made and cultures change.

The lawyers for the elephants argue that personhood has been a fluid concept in American law. They point out that humanness isn’t an essential element of personhood, nor does it alone guarantee rights. “The historic struggles over the legal personhood of human fetuses, human slaves, Native Americans, women, Jews, and nonhuman entities have never been over whether they are human, but whether justice requires that they count in law,” they write.

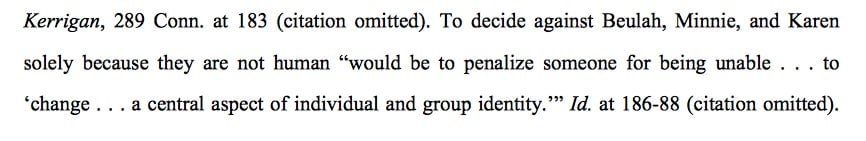

In other words, justice doesn’t ask what the race or religion or gender or being status of a litigant is but whether the litigant has a need that the law must serve. The elephant advocates are not arguing that the animals are the same as minorities but that the court must afford the elephants rights because, like the aforementioned minorities, it would be unjust to ignore the suffering of these elephants, which the law is designed to remedy. Beulah, Minnie, and Karen are “imprisoned solely because they are immutably not human, then denied protection across the board,” write their lawyers.

The elephant advocates also argue that the rights of nonhuman entities are increasingly getting recognized elsewhere in the world. New Zealand courts have acknowledged the rights and liabilities of natural entities, specifically rivers and parks, finding that they are entitled to preservation because they are live beings. In 2000, the Indian Supreme Court designated the Sikh’s sacred text, the Sri Guru Granth Sahib, a “person” able to own property.

Most importantly, the lawyers argue, the three elephants in question are legal people entitled to rights and humane treatment because they have a sense of self. The brief is supported by elephant experts who attest to the animals’ intelligence and consciousness, and to their awareness of conditions and their own existence. The elephants’ representatives say they have a sense of autonomy and of dignity, qualities that Connecticut and American law fiercely protect.

Acknowledging that the argument is novel, the brief states that times are always changing and so are ideas of what’s right. It concludes that there’s “no rational reason” to deny autonomous beings legal protection just because they’re not human and can’t change that fact.