The Federal Communications Commission has announced a “total repeal” of Obama-era net neutrality rules, a sweeping rejection of Obama-era rules meant to keep the internet a level playing field and prevent companies from charging additional fees for faster internet access. The FCC will likely vote on the rules Dec. 14, but the move surely will create a fierce court battle with parties already promising to pursue it to the Supreme Court (paywall).

“Under my proposal, the federal government will stop micromanaging the internet,” FCC chairman Ajit Pai said in a statement (pdf). “Instead, the F.C.C. would simply require internet service providers to be transparent about their practices so that consumers can buy the service plan that’s best for them and entrepreneurs and other small businesses can have the technical information they need to innovate.”

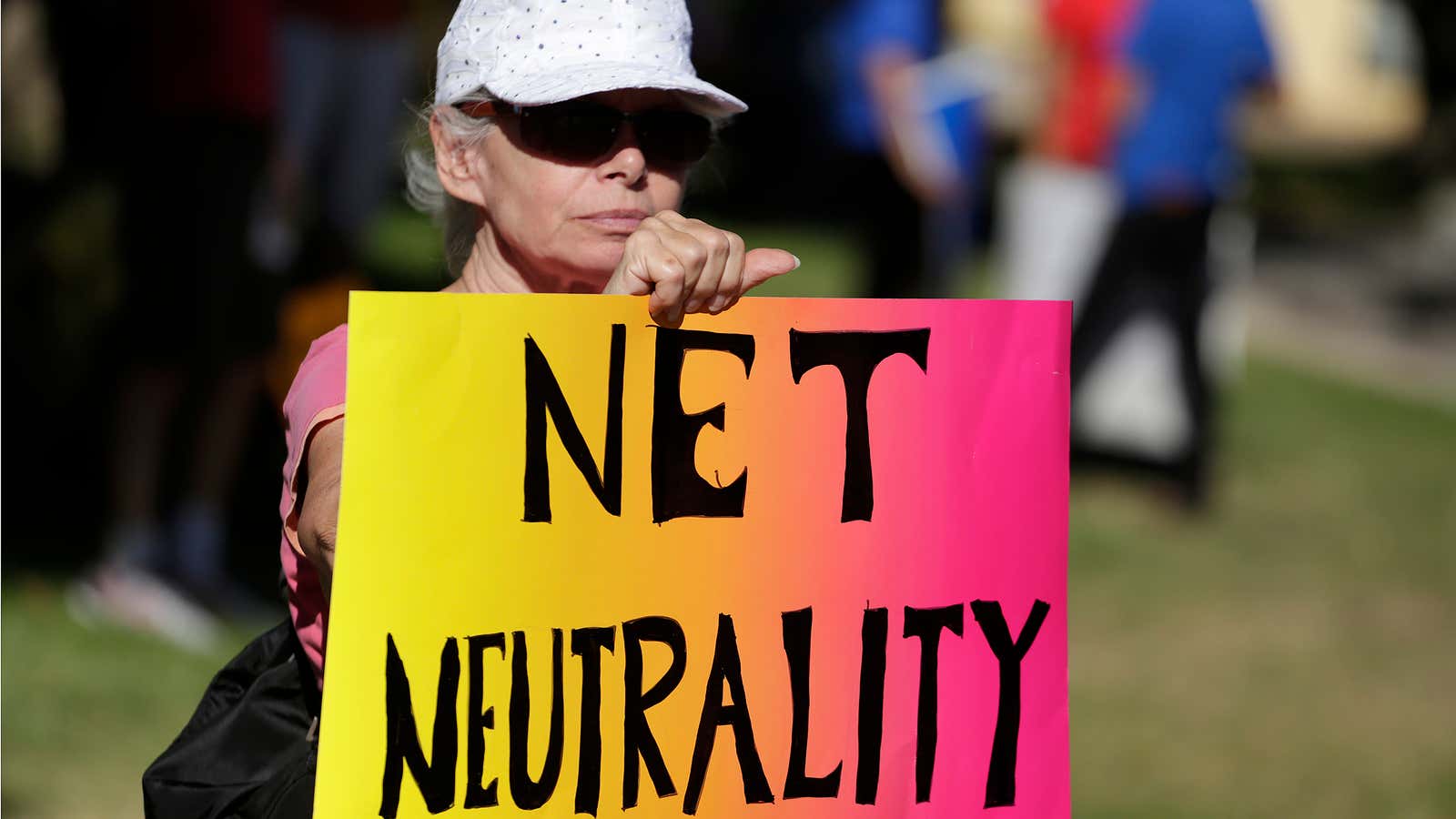

The move has already set off a furious fight over how the government should regulate companies connecting Americans to the internet. No less than 21 million public comments (many of them from bots or dubious sources) were submitted to the FCC’s website when it originally opened for comments.

In theory, Republicans and Democrats agree on a free and open internet. In policy terms, the disagreement is bitter. Net neutrality is generally defined as ensuring internet service providers do not block, slow, or otherwise discriminate against specific content and applications. An internet without these rules could see customers pay more for certain services (such as Netflix), and internet providers degrade internet speeds unless companies agree to pay more, which could exclude startups from the web in favor of deep-pocketed incumbents.

Democrats want to treat all content equally with strict agency oversight based on a history of abuse by telecoms. Republicans argue that letting the industry rely on voluntary guidelines and arms-length regulation by the Federal Trade Commission for anti-competive or abusive behavior is preferable. Federal authority to regulate the internet is seen as a potential abuse of power and could stifle innovation.

The rules proposed by Pai, an appointee of President Donald Trump, fall squarely on the Republicans’ wish list. The draft rules would lift a ban on blocking or slowing web traffic (so-called paid fast lanes), scrap regulatory authority to police behavior deemed unreasonable by the FCC, and overturn the FCC’s legal basis to enforce net neutrality provisions by dropping telecoms’ classification as utilities. The plan would require, Politico reports, internet service providers to tell customers when they are blocking or throttling content.

Pai has pledged to protect net neutrality by handing enforcement off to the Federal Trade Commission, which has latitude to enforce “truth in advertising” commitments for public statements made by internet providers. US Telecom, the trade association representing internet providers, has pledged to uphold net neutrality principles, although the specifics are still hazy.

Pai told PBS the Obama rules will hinder investment to expand broadband. “My concern is that, by imposing those heavy-handed economic regulations on internet service providers big and small, we could end up disincentivizing companies from wanting to build out internet access to a lot of parts of the country in low-income, urban and rural areas,” he said.

That argument is still speculative. Investments by telecoms since the FCC adopted a stricter net neutrality stance have not changed much (although this could take years to appear in the data). The net neutrality advocacy group Free Press disputes the argument, saying that investment is affected by interest rates, competition, economic growth and consumer demand. “Net Neutrality and Title II are benefiting businesses and internet users alike,” its report argued. “The case is clear. ”

If Pai succeeds, he will effectively erase the 2015 Open Internet Order that categorized internet service providers as utilities. The 3-2 party-line vote gave the FCC clear legal authority to enforce the strongest net neutrality principles to date. The agency’s previous attempts to do so under a different legal designation had been rejected by the courts since 2009.

Former FCC chairman Tom Wheeler backed the 2015 vote saying, “the Internet is simply too important to allow broadband providers to be the ones making the rules.” The vote did not change the way the internet, or internet service providers, operated. Instead, it gave the FCC authority to enforce previously agreed upon principles. “This is no more a plan to regulate the Internet than the First Amendment is a plan to regulate free speech,” Wheeler said.

But the move was fiercely attacked by telecoms and allies in the Republican Party. “Overzealous government bureaucrats should keep their hands off the Internet,” then House Speaker John A. Boehner (R-Ohio) said in a statement (paywall). “More mandates and regulations on American innovation and entrepreneurship are not the answer, and that’s why Republicans will continue our efforts to stop this misguided scheme.”

Washington is still waging the same battle today. As Jim Cicconi, AT&T’s head of public policy, prophetically wrote after the 2015 vote, the FCC’s partisan split (three Democrats defeating two Republicans) “is an invitation to revisiting the decision, over and over and over.” So it has been. The latest proposal will likely be approved this December in a 3-to-2 vote along party lines.

Yet Pai’s strategy may be to use the repeal of net neutrality rules to force the hand of Congress. Those familiar with FCC deliberations say (paywall) abdicating its net neutrality authority could pressure Democrats into cooperating with Republicans on passing a bill. Republican Sen. John Thune (R-S.D.) has offered to hammer out net neutrality legislation with Democrats in the past. Activists such as Berin Szóka, president of tech policy think tank TechFreedom, argue “only Congress can put net neutrality on a sound legal footing.”

If this is Pai’s strategy, it seems likely to fail. Congress has punted this question for years. Net neutrality legislation circulated in 2015 never made it to a vote, and the Telecommunications Act hasn’t been revised since 1996. Congress has failed to pass a single major piece of legislation since Trump assumed the Presidency 305 days ago, despite the GOP’s unified control of government. Few bi-partisan bills of consequence have seen the light of day.

Net neutrality may prove to be yet another casualty of America’s spreading political paralysis.