What Thanksgiving looks like for Flint, the city without safe drinking water

Thanksgiving Day will be the 1,308th day of the Flint water crisis. For residents, that’s 1,308 days without being able to drink from the tap. Flint’s presence has waned in the news, but it remains a very real crisis for those in the city that still stack pallets of water bottles in the corner of their kitchen and can’t turn on the faucet for a glass of water.

Thanksgiving Day will be the 1,308th day of the Flint water crisis. For residents, that’s 1,308 days without being able to drink from the tap. Flint’s presence has waned in the news, but it remains a very real crisis for those in the city that still stack pallets of water bottles in the corner of their kitchen and can’t turn on the faucet for a glass of water.

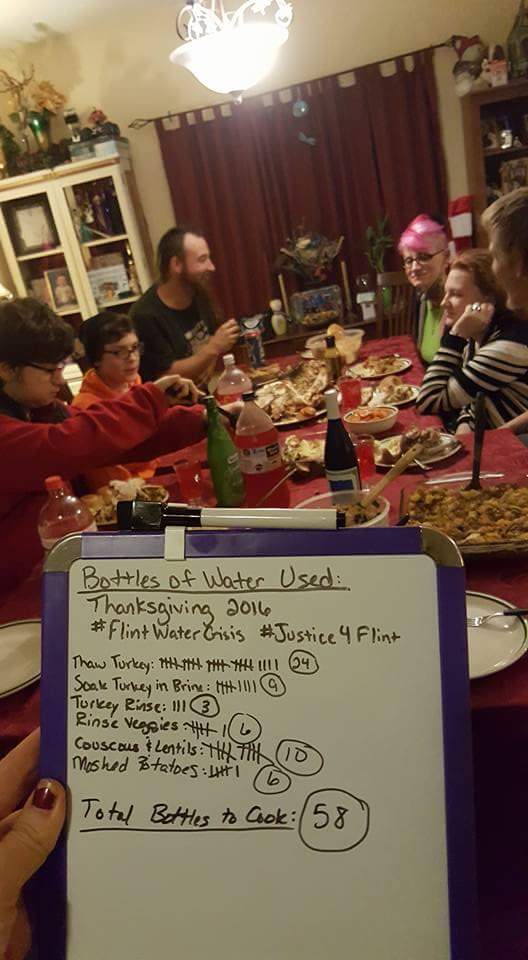

Cooking a Thanksgiving meal with bottled water is a unique challenge. Melissa Mays used 58 bottles to cook her family’s Thanksgiving meal last year. “I ended up with blisters on my fingers from opening that many bottles,” she told Quartz over the phone on Tuesday (Nov. 21).

She kept a tally on a whiteboard of how many bottles she needed for each task, and posted it to Twitter, which she plans to do again this year:

- Thaw turkey: 24 bottles

- Soak turkey in brine: 9 bottles

- Turkey rinse: 3 bottles

- Rinse veggies: 6 bottles

- Couscous and lentil: 10 bottles

- Mashed potatoes: 6 bottles

Mays, who has become a water activist since the Flint crisis began, will be cooking with her three teenage sons and her husband again this year. On Wednesday, she’ll drive to a pickup location where churches, community groups, and the city give out cases of water with 24 bottles in each case. “We’ll get eight cases, cause that’s the maximum,” Mays says. “They’re only open between noon and six. So I’ll have to go on my lunch hour.”

On Mays’ menu this year is turkey, mac and cheese, shrimp, vegetables, and desserts. “My family is native so it’s a sensitive holiday. So we’re making a traditional native desert—blackberry dumplings—and vegetables with traditional spices,” Mays says. “I’ll make an apple custard pie; you have to soak and slice the apples—it softens them to make a shape of a rose. It’s a lot of little things like that you wouldn’t think of.”

“The shrimp will have to be thawed in bottled water, and the kids love mac and cheese so of course that has to boiled in water,” Mays continues. “We soak the turkey in brine, and rinse the vegetables. We use fresh vegetables, cause that’s what’s recommended for the poisoning,” she says, referring to lead poisoning—green leafy vegetables are recommended to help reduce lead absorption. But nothing about cooking with bottled water is simple; “It’s hard to break yourself from carrying the vegetables over to the sink—you’d normally tear the kale and collards while you’re rinsing them. But now it’s a two-person job: You don’t have enough hands to pour the bottles over while you tear. It makes you realize what you took for granted.”

Mays, like most people in Flint, still relies entirely on bottled water for anything edible. She uses water from the tap only for flushing the toilet and washing dishes. Her water bill still comes to $200 every month, and, she says, she’s been threatened in the past with foreclosure for not paying it on time, even though she can’t drink the water.

Day to day, living on bottled water becomes a routine. But cooking the Thanksgiving meal is an acute reminder of the situation Flint residents have been in for over three years.

“It’s a reminder that you’re not normal,” says Mays. “Of course, we didn’t do this to ourselves. You can’t believe it’s another year of doing this.”

“We’re still in a crisis.”

The year 2020. That’s the soonest Flint residents might be able to have confidence in their water; 2020 is when the state expects all 18,000 lead pipelines in Flint to be replaced. The process of digging up pipes has begun, but the construction could also be inadvertently disturbing more contaminants, says Suzanne Selig, a professor of public health at the University of Michigan-Flint.

Selig, who lives in Flint, also teaches free “water crisis” classes, open to the public. In a city where no one trusts the government and information feels unstable, a university professor explaining the situation in clear terms is a resource. “We’re continuing to get mixed messages” from local officials, Selig says. “The destruction of trust—if it can ever be rebuilt, [it] won’t happen for a long time.” So the room at her classes is always packed. “We had 150 at the last one.” Her next class is the Monday after Thanksgiving.

“We’re not in headlines any longer but we’re still in a crisis,” Selig says.

Technically, the lead should be reduced to safe levels by the filters given out by the state and local government. That might make people feel safe to wash their dishes, but almost no one is drinking from the tap, even with the filters. Unlike some other Flint residents, Selig will brush her teeth with the filtered tap water and makes one cup of tea with it in the morning. “But the rest is bottled water,” she says.

Selig and others worry about other toxic substances in their water, like Legionella, a deadly pathogen that leads to Legionnaire’s disease. Several Michigan state officials have been charged with involuntary manslaughter for a Legionnaire’s outbreak in the water that killed at least 12 people at the height of the city’s water crisis. Local officials didn’t report finding Legionella in the water system to the state for more than a year. So no one is touching the tap water.

“People don’t trust the water supply. I don’t trust the government right now,” says Selig. She hasn’t had problems showering in the water, but her friends and neighbors have; “Clumps of hair coming out, skin rashes,” she says. “Their pets were getting sick.”

Whenever they run out, Selig and her husband drive to one of four locations around the city where bottled water is distributed freely. The volunteers who pass out the water are always friendly, she says. “There’s so much support here among the residents.”

As Melissa Mays gets ready to cook another Thanksgiving meal with bottled water, she says she can’t help but think about places where water is even more inaccessible.

“It makes you a lot more grateful for what you do have,” Mays says. “We’re grateful we have bottled water—we know Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands don’t even have water. It reminds us how important to life this is.”

“This country is supposed to be taking care of us. It doesn’t seem like the response is there. Especially with Puerto Rico and Flint—we were both under government control. We’re both hearing crickets.”