Expensify’s “smart” scanning technology was secretly aided by humans

Expensify is a software company that automates the painful task of compiling expense reports. It does this using “SmartScan” technology that can supposedly glean details like merchant, date, and price from a picture of a receipt.

Expensify is a software company that automates the painful task of compiling expense reports. It does this using “SmartScan” technology that can supposedly glean details like merchant, date, and price from a picture of a receipt.

Since it started in 2009, Expensify has raised just shy of $30 million from investors including Uber co-founder Travis Kalanick. The company claims to process billions of dollars a year, and reimburse millions of dollars a day, aided by SmartScan and its investments into “automation in the expense reporting process.” Its 4.5 million users and 300,000 corporate clients include some of today’s hottest startups, such as Uber, Square, Snapchat, and Instacart.

SmartScan is presumably a selling point for Expensify, since the receipts it handles can contain sensitive personal information, like names, purchase details, email addresses, and even bank routing numbers. So it was awkward when, last week, the company was caught posting receipts to an online marketplace for freelancers so that their contents could be transcribed not by SmartScan, but by humans.

Rochelle LaPlante is a worker for Amazon Mechanical Turk, an online hub where an army of Amazon-approved independent contractors complete “human intelligence tasks” (“HITS”) such as transcriptions, image tagging, and line-editing, usually for a couple cents. The name Mechanical Turk alludes to the “automaton” chess player that astounded Europeans in the late 18th century, but was later revealed to be an elaborate hoax controlled by a hidden human chess master.

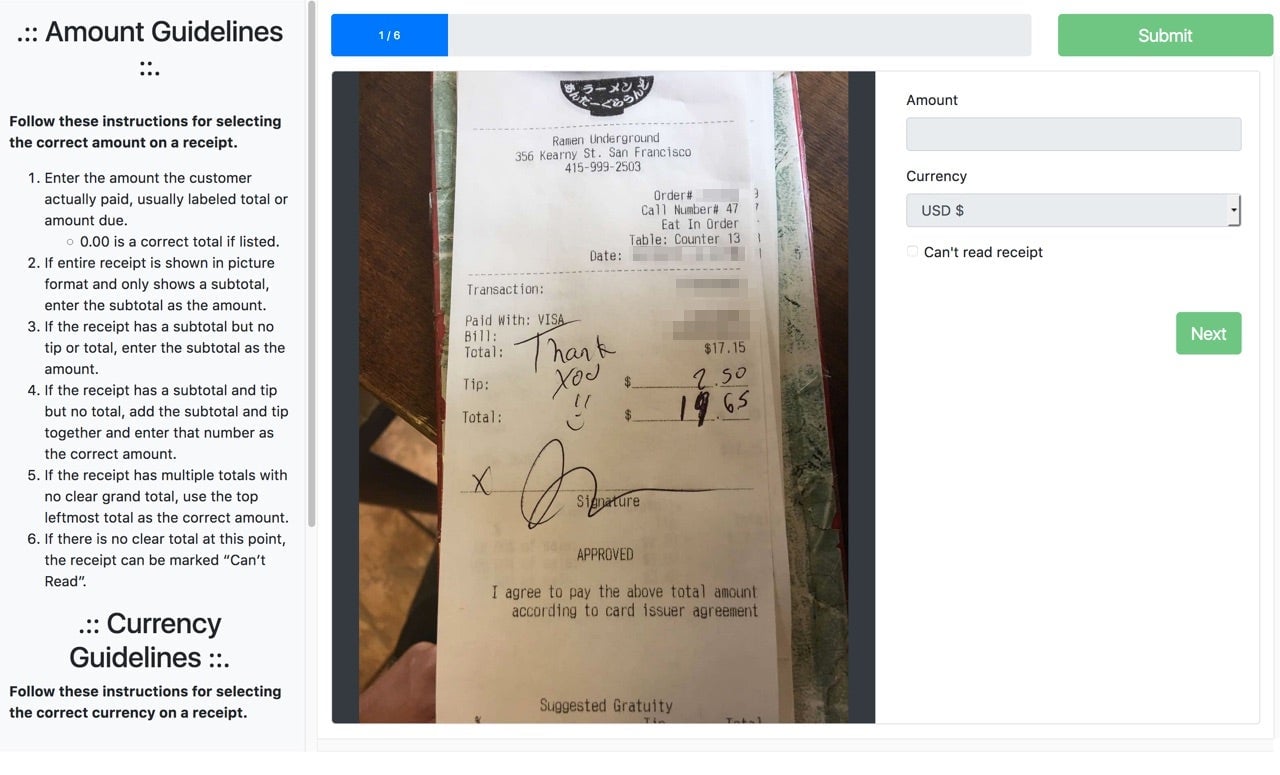

Last week LaPlante was browsing HITs on Mechanical Turk when she spotted several postings from Expensify bearing “people’s very personal information,” she told Quartz. These included an Uber receipt with the customer’s name and dropoff/pickup spots; a receipt from a bakery in California; a receipt from a ramen place in California; and an invoice for a stay at a hotel in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, complete with the guest’s name, bank account number, and itemized expenses, mostly involving the bar, according to screenshots she provided to Quartz.

Around the same time, another Twitter user reported browsing Expensify jobs on Mechanical Turk to see “boarding passes, hotel receipts… medical receipts, addresses, signatures.” On each posted task reviewed by Quartz, “guidelines” instructed the worker to “enter the amount the customer actually paid.”

The line between automation and humans blurs more often than Silicon Valley might like to admit. Facebook hired thousands of people this year to moderate content on its social network, after algorithms repeatedly failed to do the job. Uber depends on more than 2 million drivers worldwide to provide rides every day, as well as employees at headquarters to make sure enough of those drivers are on the road. Behind much of Google’s digitization of books and maps is random people on the internet, conscripted using reCaptcha. Expensify is just another example.

Employing real people is expensive, of course, and much tougher to scale than an algorithm. Expensify is still a startup, and venture capitalists are generally much less eager to fund technology powered in part by humans than technology powered purely by algorithms. Expensify’s customers might not be pleased to know strangers on the internet could be reading their sensitive expense reports.

After LaPlante called the company out on Twitter, Expensify founder and CEO David Barrett published a blog post on Nov. 25 about a “new privacy-enhancing feature” the company is rolling out, “Private SmartScan.” Barrett didn’t deny that humans enabled SmartScan, but said the Mechanical Turk tasks were part of testing for Private SmartScan, which “enables organizations to take direct control of the privacy and security concerns of human transcription” by hiring their own “24/7 team of human transcription agents” on Mechanical Turk. Quartz emailed Barrett for comment and has not heard back.

In a second post on Nov. 27, Barrett admitted that Expensify had been using Mechanical Turk as far back as 2009. He said it replaced those workers in 2012 with a “private workforce of non-Turk SmartScan agents.” (Still humans!) Mechanical Turk, he said, was reintroduced this year to test Private SmartScan.

The receipts on Mechanical Turk belonged to “less than 0.00004% of users—none of whom are paying customers,” Barrett said, adding that, at any rate, there is nothing important on a receipt, “that’s why receipts are so commonly thrown out—because they are literally garbage.” Also: “anybody concerned by the real-world risks of a vetted, tested transcriptionist reading their Uber receipt should probably consider the vastly more immediate and life-threatening consequences of getting into that stranger’s car in the first place.”

“Life is not without risks,” he concluded, a statement presumably intended to reassure the companies and millions of users who entrust Expensify with the safe handling of their receipts, I mean, er, garbage.

This post first appeared in Oversharing, a newsletter about the sharing economy. Sign up here.