Tanzania’s anti-corruption government is stifling the “Swahili Wikileaks”

Dar es Salaam

Dar es Salaam

Maxence Melo is a man who knows the insides of Tanzania’s courthouses all too well.

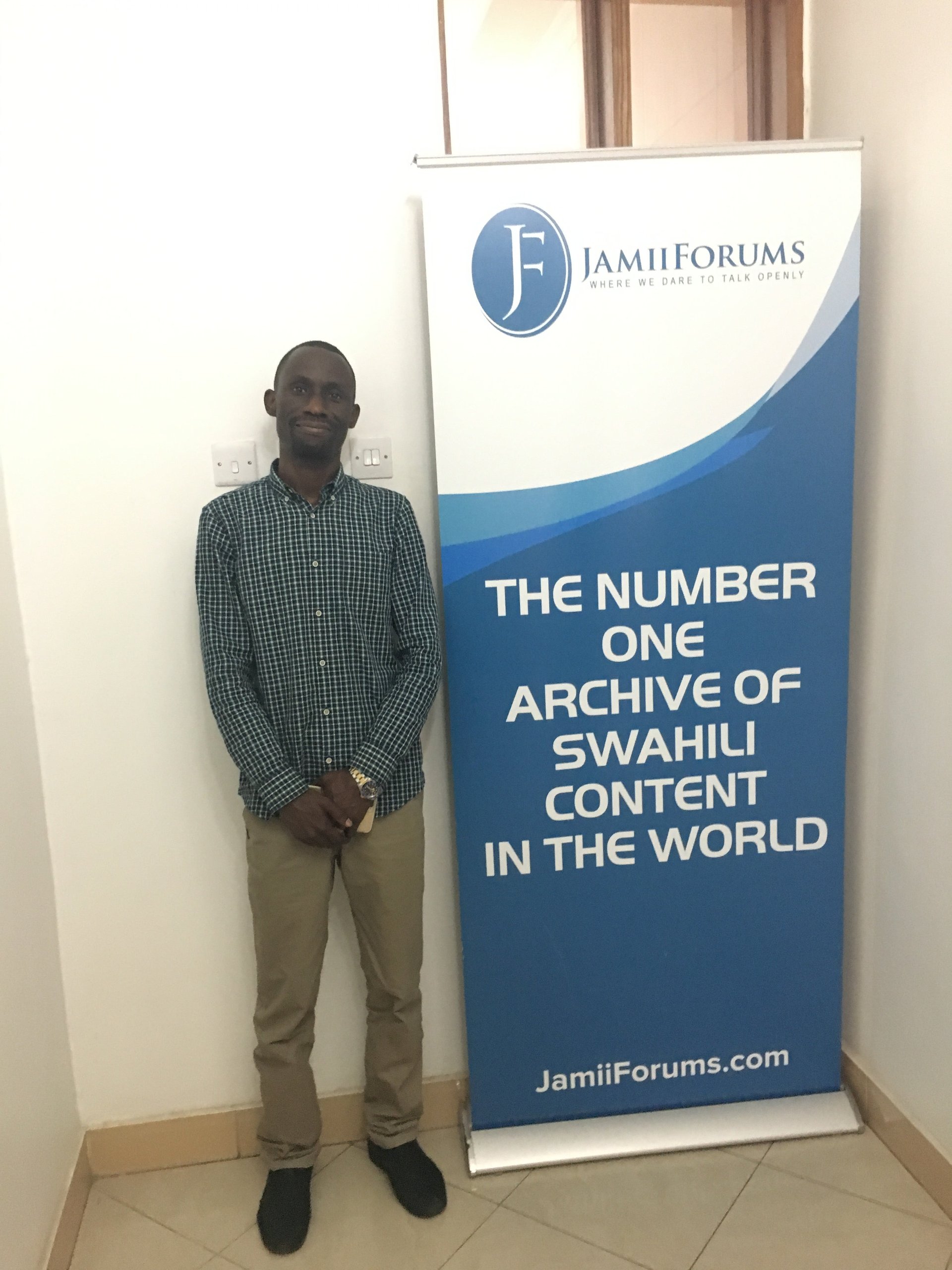

In 2017 alone, he has appeared in court about 51 times he says, accused of obstructing justice, operating an unregistered website, and refusing to reveal the identities of users who shared sensitive information. Melo, 38, is the co-founder of Jamii Forums (JF), a popular Swahili social media networking site that is part whistle-blowing platform and part citizen journalism outlet. Since it was founded in 2006, he has been harassed, threatened, detained, interrogated, and at one point barred from traveling abroad.

And over the last two years, as president John Magufuli’s government tightened its grip on both the digital and traditional media spaces, Melo has become the poster boy for the crackdown.

The clampdown has taken on a new significance as the government recently introduced a law that would give it unfettered powers to police the web. The proposed Electronic and Postal Communications (Online Content) Regulations 2017 calls for the registration of blogs and online forums, orders internet cafes to install surveillance cameras, prohibits material deemed as “offensive, morally improper” or that “causes annoyance,” and recommends a fine of 5 million Tanzanian shillings ($2,230) or 12 months in jail for anyone found guilty.

Observers and activists have argued that some of the definitions provided in the law are ambiguous, violate individual privacy, curtail citizen’s right to free speech and expression and go against the spirit of an open internet.

The law is a culmination of the slew of laws that have since 2015 has given officials broad discretion to restrict media organizations on the basis of national security or public interest. Before he left power in 2015, former president Jakaya Kikwete signed a cybercrime law—informally known as the “Jamii bill”—that gives authorities powers to jail those who offend the president or publish false information.

A Statistics Act also made the publication of any data not approved by the National Bureau of Statistics illegal. Barely a month after taking office, Magufuli signed the controversial Media Services Bill, replacing independent media oversight mechanisms with a government-controlled one, and requiring all journalists to get accreditation from a government-appointed board.

Melo, who alternately uses the terms whistleblower, investigative reporter, and citizen journalist to talk about his work, says the government operates from the notion that they are out to defame public officials or unfairly scrutinize government work. “You need to know the intent isn’t to malign someone but to help the country keep its resources,” Melo told Quartz at the Jamii Media headquarters located on the outskirts of Dar es Salaam. “Whistleblowers are not criminals.”

Rocky start:

In some ways, Jamii Forums—or at least its current disposition—was an idea born ahead of its time. It came about at a time when online community websites like Kenya’s Mashada were being revived in the mid-2000’s as a way to connect, engage, and inform both Africa’s local and diaspora populations. The site was also established during a time when independent media outlets regularly faced restrictions in Tanzania, and when barely 1.3% of the country’s population had access to the internet. And even though it started as a social networking platform known as JamboForums, it quickly had to tack to cover news and champion freedom of speech.

The portal also filled an important lacuna by making Swahili its lingua franca, bringing into the fold tens of thousands of people left out by English-speaking community websites.

The site’s growth and influence were immediately noticed by authorities, who frustrated it by saying the word “Jambo” had been copyrighted. In 2008, the forum was renamed into Jamii Forums, and Melo now went on to build a community and a network, both in the public and private spaces, that would help him attain documents and generate content and analyses of current affairs. He hired investigative reporters in different parts of the country, made contacts in the intelligence and donor circles, and made friends with leaders of major political parties.

“The internet was assumed to be a tool to entertain yourself,” Melo, a trained civil engineer, said. “I knew that as long as we had to fight corruption, it wasn’t going to be an easy task.”

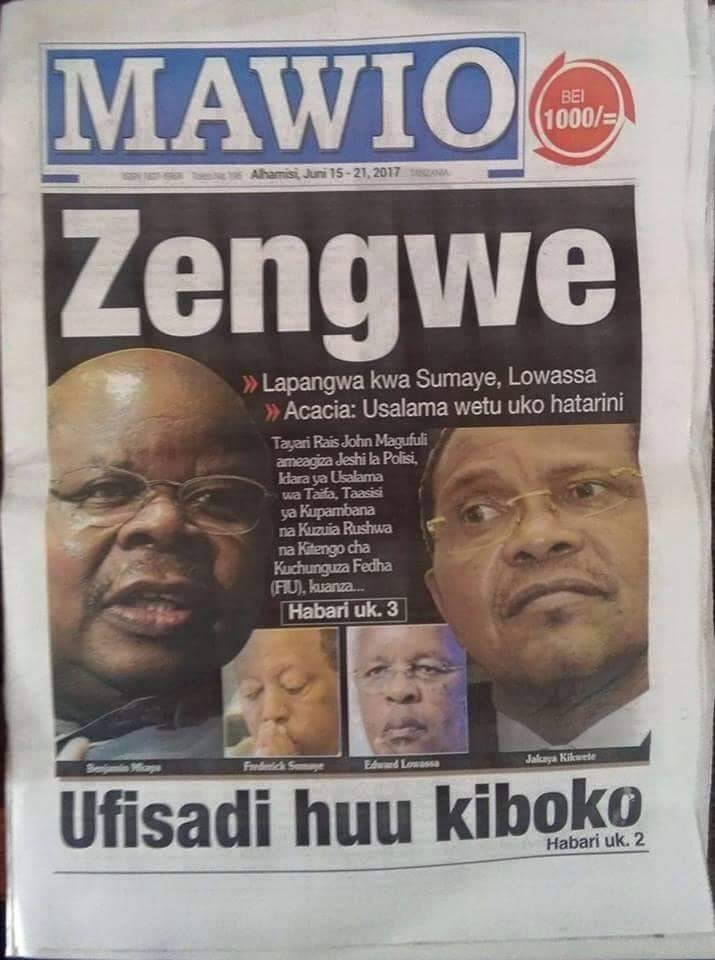

In Feb. 2008, Tanzania’s prime minister Edward Lowassa resigned and his cabinet dissolved after JF published documents implicating him in a corrupt energy deal with US-based company Richmond Development. The exposé was the highlight of a motley of cases that JF would publish in the next decade, leading to more government sackings and donor distrust—and for Melo, an endless stream of interrogation and arrests.

Since then, JF has grown to be a platform with more 420,000 members, including verified accounts by cabinet ministers, members of parliament, and businessmen. The site has more than 4.3 million followers on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram combined and has been described as both the “Tanzanian Reddit” and a Swahili version of WikiLeaks. With increased internet penetration, JF has integrated more and more Tanzanians into the social media space, to discuss, share, question, and hold the powerful accountable. About 72 people work on the platform now, monitoring and approving between 80,000 to 100,000 comments daily, according to Melo.

Growing fears:

After multiparty democracy was introduced in 1994, Tanzania became more open country both politically and economically. For two decades, both presidents Benjamin Mkapa and Kikwete served an image of Tanzania as a country open for business. But Magufuli has completely changed the tone, introducing a leadership style harking back to the days of the socialist rule of the country’s first president Julius Nyerere. Known as the Bulldozer, he has led a very loud effort to tackle corruption, banned the export of unprocessed minerals, and squeezed mining companies for higher revenues and royalties.

But this heavy-handedness has now trickled to media and journalism sector.

Across Tanzania, social media outlets like Facebook and WhatsApp have increasingly thrived, assuming greater importance in political campaigning and in the dissemination of news. But after a few rosy years, Melo now says Magufuli’s government started to reverse the paltry gains achieved through digital communication. As early as 2014, he said, government agents started telling him, “There’s a Jamii Forums law that is coming. Like it or not, it will be passed.” The law, sanctioned to fight bank fraud and mobile money theft has been used to prosecute online users critical of the government.

On election day 2015, JF was targeted in a DDOS attack, rendering it inaccessible (p. 12) for days. Melo is consistently asked to reveal whistleblowers, imprisoned for operating a site without the .tz domain, accused by top state officials of working on behalf of the opposition Chadema party, and his website reportedly “cloned” so as to disrupt conversations of opponents.

Swahili, which was a strength for JF from the onset, now constitutes a “barrier,” stopping many stories or threads from going viral. Drawing on the example of Kenyans on Twitter, Melo says they can pull the world’s attention to local governance issues, simply because they “could write everything in English.”

Angela Quintal, the Africa program director at the Committee to Protect Journalists, says Tanzania’s attempt to police the web erodes privacy and makes the state into “Big Brother.” “The sledgehammer approach to the digital rights of citizens are not the actions of democrats, but of a government who fears the very people who voted it into power,” said. “It is a slippery slope towards despotism.”

The panoply of laws scapegoating digital media outlets is also targeting traditional outlets like newspapers. This year, both the Mwanahalisi and Mawio newspapers were banned in Tanzania for one and two years respectively, prompting human rights and media organizations to decry the state’s actions. “Everyone is worried,” says Simon Mkina, editor of the suspended Mawio weekly.

Ephraim Kenyanito, a program officer with digital rights advocacy Article 19, says there’s need to enhance “connections between internet freedom advocates, techies, and lawyers to be able to point out and challenge the constitutionality of these provisions.”

Melo says that no matter what happens, the government’s crackdown on the forum only strengthens the collective urge of their user base to stay engaged. Jamii Media says that 75% of Tanzanian lawmakers browse the site regularly—and recently embarked on a project aimed at following up on election promises to improve service delivery.

As the site generates revenue, Melo also hopes to widen the conversation beyond Tanzania and to enter both the Anglophone Kenyan market and Francophone in the DR Congo. By going into these markets, the hope is to also archive the conversations happening among Africans in Africa.

“I like solution-based journalism,” he said. “Let’s be critical about what are the issues [and] how can we tackle them. We want people who know their stories.”