When people talk about the intersection of social media and politics, the focus is usually on the ways that Facebook and Twitter are changing how politicians connect with voters. Things are a bit different in Africa, where the mobile phone has changed not only the way people communicate but the very nature of their financial lives. In Tanzania, it is WhatsApp, the mobile instant-messaging app that boasts 900 million users around the world, that has transformed political communication in the country.

A general election campaign is underway in the country, pitting presidential candidates John Magufuli from the ruling party Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM) and Edward Lowassa representing the opposition coalition Ukawa. The vote for a new president and parliament will take place on Oct. 25.

“WhatsApp is a preferred tool of choice for propaganda, mudslinging, and negative messaging,” a digital media strategist tells Quartz, requesting anonymity in order to openly discuss how the platform is being used by political parties. The app is the go-to platform for “messaging you can’t say yourself that surrogates can do for you,” the strategist adds. In this way, WhatsApp networks are similar to Super PACs in the US, the officially unaffiliated groups that nonetheless raise money and cater directly for their chosen candidates’ whims.

Data in Tanzania on WhatsApp usage are scarce, but political operatives are flocking to the platform because it cuts across all demographics, unlike other social networks.

This is partly because WhatsApp is more easily accessible than either Facebook or Twitter to Tanzania’s 11 million internet users. “A lot of feature phones have Whatsapp pre-installed,” Maxence Melo, co-founder of Jamii Forums, one of Tanzania’s most popular online platforms, tells Quartz. “People do not have the technical know-how to install apps. So its easy [because] of these feature phones, Chinese phones, to have WhatsApp.”

Additionally, mobile carriers are now offering cheap on-demand data bundles that bolster the popularity of WhatsApp. A user can buy 60MB worth of data for up to a week for as little as Tshs2,000 ($1). Because of this, Melo estimates that there could be as many as 8 million people using the app. That’s a lot more than the country’s 2.5 million registered Facebook users. Meanwhile, Twitter, which does not release country-specific figures, has perhaps 700,000 users, according to local sources.

How political parties are using WhatsApp

WhatsApp is “a network platform that is very easy to use to spread propaganda,” January Makamba, CCM’s campaign spokesman and the outgoing deputy minister of communication, science, and technology, tells Quartz. “A lot of it is negative.”

“People are sharing a lot of stuff but mostly they are using it to manipulate,” Melo points out. “Taking screenshots to show that their opponents are [struggling].”

On WhatsApp, you can’t send messages to people unless you have access to their phone numbers. That means political parties need to get loyal surrogates to push messages to their networks. “The substance of the messaging is superficial,” the digital strategist says. “It is about placating supporters and antagonizing opponents. “

Additionally, WhatsApp is a way for parties to test negative messages they want to break into the broader news cycle. “It becomes a catalyst, a driver of what one should do next,” the digital strategist explains. Once something is seen to resonate on the relatively closed network of WhatsApp, operatives will push it to other social media platforms. “If it works on Whatsapp then it’ll go on Twitter,” the strategist says.

An example of this happened earlier this month when a video purporting to show Ukawa presidential candidate Edward Lowassa telling a Lutheran congregation to pray that he wins because its about time that a Lutheran becomes president in Tanzania. The clip bounced around on WhatsApp, then jumped to Twitter, and finally to the mainstream media.

Despite its closed nature, the ubiquity of WhatsApp on Tanzanians’ phones means that messages on the platform have a much better chance of going viral than on any other social sites, as Melo explains:

It’s easy for something to go viral. For example, I am in over 20 Whatsapp groups. So if I get a certain message that I want to go viral, I put in all groups. Someone who is in the same group takes it to other groups, so it becomes viral immediately.

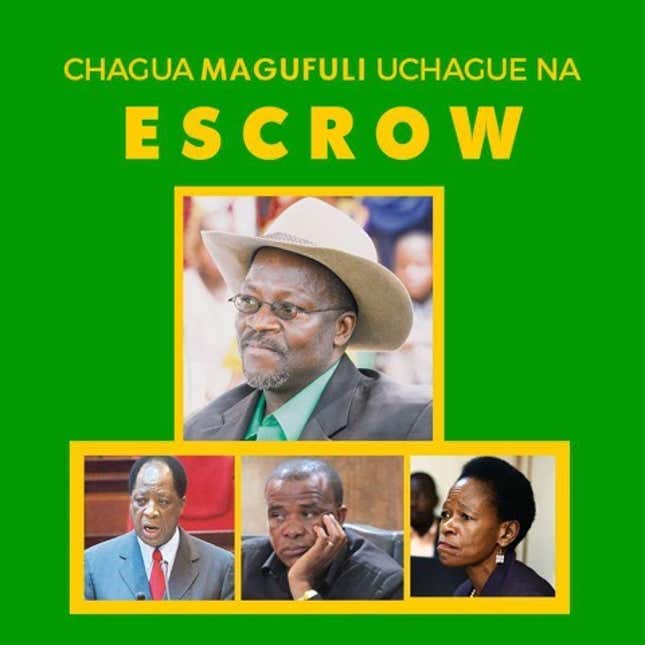

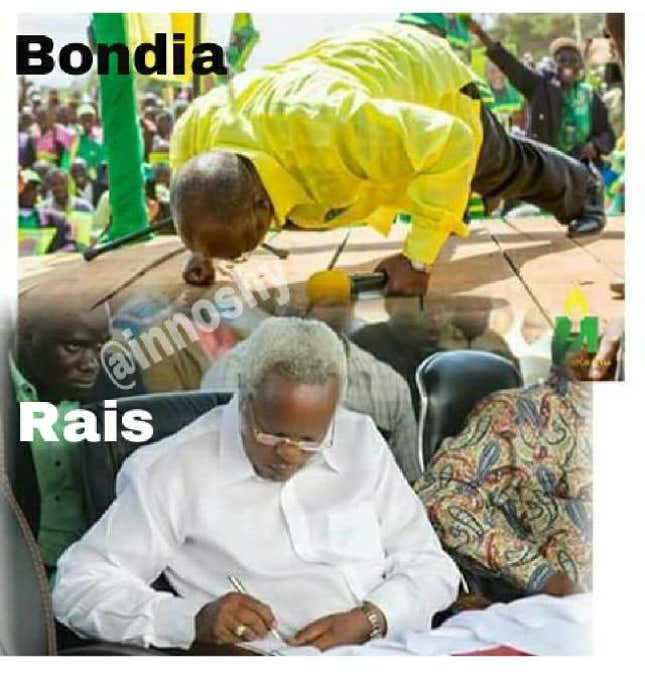

Sadly, there is little meaningful discussion or debate on this new platform for political engagement. For the most part, what gets shared on WhatsApp are images and memes, as those are easily digestible for an electorate that is not looking for substance, analysts say.

“This is a social media driven election, where people want easy to consume content that doesn’t make us think a lot,” the digital media strategist says. “It’s like Arsenal versus Chelsea rather than about issues.”