Investing in BlackRock was one way to beat the market this year

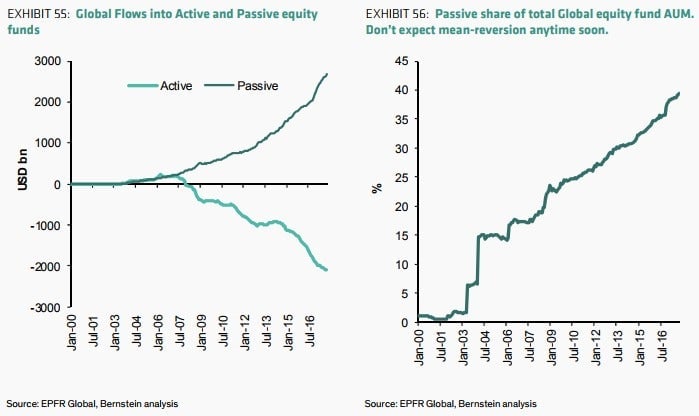

The battle between human portfolio managers and funds that track indexes has swung clearly in the indexes’ favor: Passive exchange-traded funds (ETF) for stocks have now attracted $1.7 trillion of flows since 2007, while $1.2 trillion has drained out of actively-managed funds, according to fund-manager Pictet.

The battle between human portfolio managers and funds that track indexes has swung clearly in the indexes’ favor: Passive exchange-traded funds (ETF) for stocks have now attracted $1.7 trillion of flows since 2007, while $1.2 trillion has drained out of actively-managed funds, according to fund-manager Pictet.

The reasons for passive investing’s popularity are well founded. Over the years, professional portfolio managers have failed (paywall) to consistently outperform broad-based index funds, and savers have generally been better off with a cheaper, benchmark-tracking alternative. Many investors appear to have woken up to that realization and are pouring their money into the exchange-traded funds. There are now more indexes than there are US stocks.

Paradoxically, one way to beat the market this year was to invest in BlackRock, the world’s biggest asset manager and one of the big beneficiaries of the passive boom. BlackRock and Vanguard Group together manage (paywall) more than $10 trillion, almost as much as the gross domestic product of China. At this point, titans like BlackRock that provide ETFs are perhaps becoming more like “highly entrenched, high-margin toll roads for trillions of dollars of retirement savings,” according to the Financial Times (paywall).

One of the debates in 2017 has been whether the tsunami of money flowing into passive investing is becoming too much of a good thing—will the influx of cash into funds that simply track an index eventually weaken corporate governance? Will stock values get out of whack if there aren’t enough stock pickers around to decide which to buy and sell?

Barbara Novick, a co-founder of BlackRock, wrote in the Wall Street Journal (paywall) last month that indexed assets account for less than 20% of the global stock market. If stock prices get too far out of sync, she argues that stock pickers will have an easy time finding winners, which would likely reduce or reverse the flow of money into passive strategies.

Alliance Bernstein, a fund manager that wrote this year’s most talked-about criticism of passive investing, says passive’s share is closer to 40%. Bernstein analyst Inigo Fraser-Jenkins argued that a Marxist economy at least has a planning process; a market ruled by passive investing could be even less efficient.

Yale economics professor and Nobel prize winner Robert Shiller is also cautious, according to an interview with CNBC. If you believe the market is supposed to be all-knowing, incorporating the knowledge of many investors, then “how in the world can the market be all knowing if not as many people are trying to beat it?” He said passive indexing free-rides on other peoples’ work, and it’s pseudo-science to think such benchmarks are perfect.

The tipping point, if there is one, is unknown. As their assets under management swells, the safe bet for 2018 is that scrutiny of giants like BlackRock, Vanguard, and State Street will increase.