In a low-interest-rate world, older Americans might want to scale back their retirement dreams

Low interest rates are bad for savers. Federal Reserve chairman Ben Bernanke recently tried to reassure them by pointing out that most Americans are savers and borrowers, so everyone benefits from low rates. But that’s not necessarily true.

Low interest rates are bad for savers. Federal Reserve chairman Ben Bernanke recently tried to reassure them by pointing out that most Americans are savers and borrowers, so everyone benefits from low rates. But that’s not necessarily true.

Most people build wealth as they age. As you get older, your income increases and you have fewer child-related expenses. This leaves more cash to build a nest egg to fund retirement. Many people also pay down their debts as they age, such as their mortgage. According to the 2010 Survey of Consumer Finances, the leverage ratio (that’s the ratio of how much you owe to how much you own) of 55- to 64-year-olds is 11%. For 35- to 44-year-olds, it rises more than threefold to 37.3%. The more debt you have relative to your assets, the more you benefit from lower rates.

The size of your nest egg determines your lifestyle in retirement. How much money you’ll have is function of how much you saved and the returns your portfolio earned. Lower returns means less wealth, so persistently low rates can create a negative wealth effect, making people feel poorer. This can lower consumption and demand. In this respect, low rates can be bad for growth. The low rates mean smaller yields on bonds and CDs when you hold these assets to maturity. Though as Quartz’s Matt Philips pointed out earlier this week, investment in these types of assets has been declining. They now make up a small part of most people’s portfolios; many people hold stock instead, which often goes up when the Fed lowers interest rates. Savers typically own stock through their retirement accounts.

Academics and financial planners generally advise moving these funds into lower risk assets, like bonds, as you approach retirement. The stock market may offer higher expected returns, but also more volatility. You are in a better position to bear this risk when you are younger because your portfolio has time to recover from a bear market. The young are also naturally better diversified because future wages are a large share of their assets. Many soon-to-be-retirees felt good about their nest egg in August of 2008. Then the financial crisis hit and they had to revise their retirement plans when their wealth dropped 40% in just a few months.

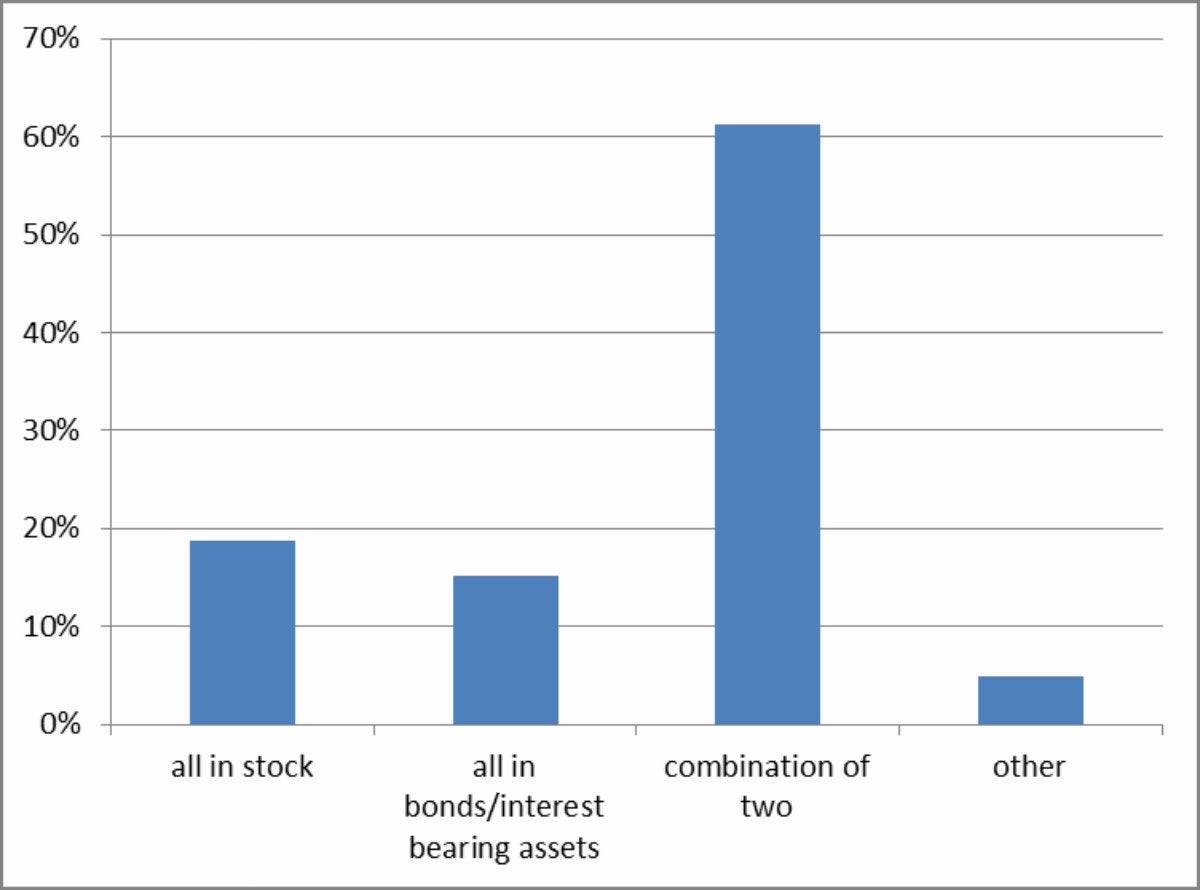

It’s not true that we needn’t worry about savers because soon-to-be-retirees are invested heavily in stock. That’s precisely what is so worrying; especially if the low rates are encouraging investment in riskier assets just before retirement. The figure below gives the breakdown of how private pension accounts are invested among 55- to 64 year-olds from the 2010 Survey of Consumer Finances:

More than 60% of 55- to 64-year-olds are invested in stock and bonds. The median equity allocation for this group is about 50%. Holding this much stock close to retirement exposes them to a significant amount of risk. Most of money they’ll need soon is subject to the daily whims of the market.

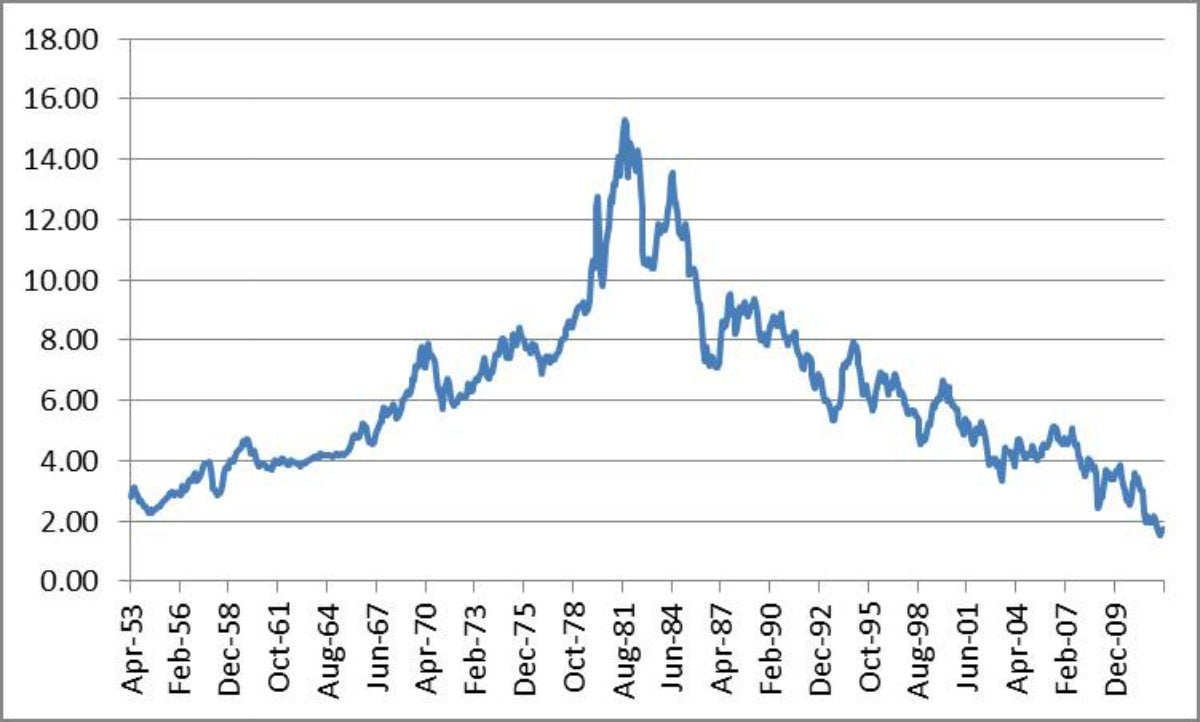

The portfolios of many soon-to-be-retirees are also in bonds. Bond investment in your in retirement account often means owning shares in a bond fund, which is a collection of many different bonds that are regularly bought and sold to maintain a particular maturity, rather than an individual bond. The return on the fund is not the yield of one particular bond; it’s based on changes in bond prices. Bond prices are higher when yields are lower. So if yields go up, bond prices fall and investors in bond funds lose money. Over the last decade, bond prices increased as bond yields fell. The figure below is the 10-year bond yield from 1953 to today:

Historically, bond prices did not behave like stock prices (which can always go higher) because yields tend to “mean revert.” That means bond yields move around some long-term average. Otherwise nominal yields could keep falling eventually earning a large, negative yield; imagine buying a bond that earns negative 25%. So it seems likely that, eventually, yields will go back up and bond prices will fall. If that’s the case, the bond funds that savers are invested in will fall in value. The desire to lower rates further only makes bond funds more expensive. This sets up bond investors for a bigger loss. The 55-plus crowd doesn’t have a lot of great choices right now: volatile stocks, low-yielding bonds, or bond funds that will probably one day fall in value. Despite Bernanke’s assurances, it hardly seems like a good time to be a saver.

Low yields are also a problem if you want to secure, stable income by buying an annuity or a bond portfolio to fund your retirement. Lower yields make this more expensive, which means lower income all through retirement. Buying an annuity is not very popular in America. But it is in Britain, where interest rates are also extremely low, because retirees must buy an annuity there.

Other savers in the economy are pension funds, companies or state and local governments who manage enormous pools of assets which fund their employees’ retirement. The low yields results in poor asset returns. So the funds must put more money into their pensions and less into investing and hiring new workers. Or, we might see pensions invest more in risky assets, as the state pension plans have done, to chase yield. This can pose a burden on taxpayers if it all goes wrong.

Bernanke was right on one thing: Increasing rates now would probably hamper the economic recovery. But that certainly comes with costs to savers.