“But what about the savers?” That cry went up yet again when the US Federal Reserve promised, earlier this month, to keep interest rates at zero at least until 2015. The Fed, of course, was trying to perk up the American economy, but in monetary policy there are always winners and losers, and—with the Fed’s interest rate target having already been at or near zero for more than four years—the losers are people with savings. Yields on CDs (fixed-term deposit accounts) have collapsed. The yields on safe bond investments, like US Treasuries, is so low that after a few years of inflation, returns on those investments are almost certain to be worth less than what investors first put in.

Ben Bernanke, the Fed chairman, took the somewhat unusual step of acknowledging some of these concerns. In an attempt to assuage them, he pointed out, “low interest rates also support the value of many other assets that Americans own, such as homes and businesses large and small.”

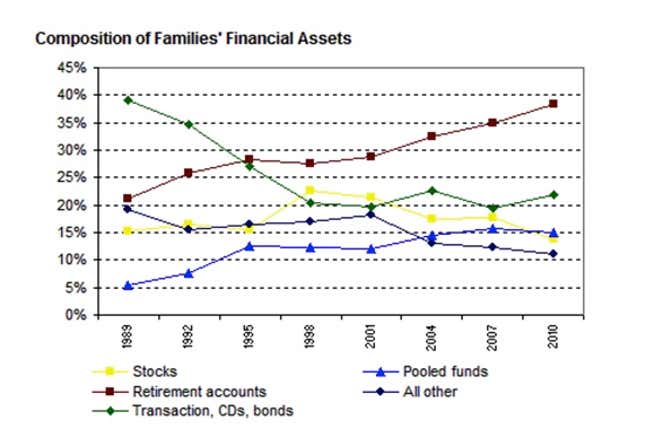

But he might also have noted that there is another reason not to worry so much about the impact of low interest rates on savers: it turns out that interest isn’t as important to savers as it used to be. Crunching the numbers from the Fed’s Survey of Consumer Finances, debt analysts at bond research firm Stone & McCarthy report that the share of interest-bearing assets such as bank accounts, CDs and bonds has nearly halved in the last two decades, from 39.1% in 1989 to 21.9% in 2010.

Conversely, retirement accounts—401(k) pension schemes, IRAs, etc—have nearly doubled, from 21.1% in 1989 to 38.4% in 2010. These are private pension and retirement plans that people can put together from a range of options; they often include some bonds, but in large part, their returns are tied to the stock market, which has been rising of late. In other words, people have a much bigger share of their financial investments in things that have been rising in price, and much less invested in things that earn (now non-existent) interest.

Even among the over-65s, whose families are much more likely than average to own a CD, such investments are a lot less common than they were in 1989, Stone & McCarthy reports. Nor are older folks much less exposed to the stock market than the country as a whole. For households headed by those 75 and above, stocks represent 43.9% of their financial assets in 2010, versus 46.8% for all households.

The upshot: the American Grandma and grandpa still have a big stake in the stock market. And the recent surge of stocks, driven largely by expectations of further Fed action, is benefiting them, as well as the rest of the country. So even for those more likely to be savers, its seems the Fed giveth, as well as taketh away.