Investors in emerging markets would like their money back now thanks

Weren’t we supposed to have gotten beyond this?

Weren’t we supposed to have gotten beyond this?

Indonesia’s stock market and currency both tanked Monday after the nation posted its worst deficit in its current account—a broad gauge of trade, financial and services payments in and out of a country—since 1989. Stocks slumped by 5.6%. Indonesia’s currency, the rupiah, hit a four-year low against the dollar after tumbling more than 1%.

In the aftermath of the global financial crisis five years ago, emerging markets became the darling of global investors searching for higher-yielding investments. (Yields on investments in developed markets were historically low, in part due to the US Federal Reserve’s ultra-low-rate monetary policy.)

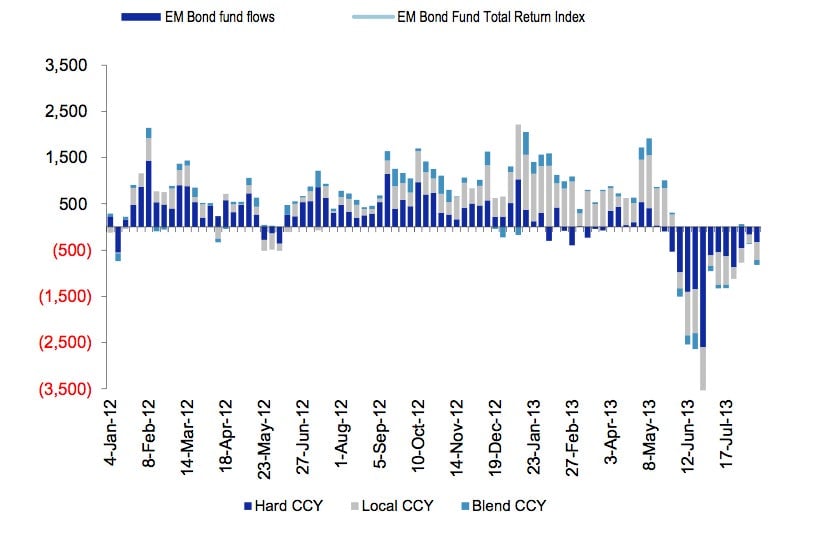

Now, as the Fed appears ready to lighten up on the support it is offering to the US market, money is retreating from emerging markets—fast. Here’s a look at outflows from dedicated emerging-market mutual funds in recent weeks, compiled by Morgan Stanley.

As the rip-tide of liquidity pours out of a country, it drives the value of the currency lower. That makes imports of crucial foreign products—such as energy—costlier. The surge in spending on imports worsens the current account deficit. That prompts still more worries about investing, setting off a further outflow of investor cash. The decline of the currency gets deeper. A spiral can ensue until you hit something known as a “sudden stop,” which pushes a country into default.

Such tidal waves of foreign investment into and out of emerging markets are a well-known problem, leading to a range of banking collapses, inflationary spirals, sovereign defaults and currency crashes. (Some have referred to them as “capital-flow bonanzas.”) They were at the heart of a slew of crises in the 1990s: Argentina, Thailand, Korea, Mexico, Turkey, Chile and, yes, Indonesia.

But, of course, the story now goes well beyond Indonesia right to the heart of the so-called BRICs—onetime market darlings Brazil, Russia, India and China—that were supposed to represent a new sort of emerging market.

And yet here we are, India’s rupee continues to collapse in value, hitting an all-time low today. Brazil’s currency has also declined precipitously. Capital flows are more heavily controlled in China, but there are signs that investors are getting leery of investing there too. That’s something to consider for those who’ve come to rely on such countries to generate global economic growth in recent years. Stay tuned.