The role of aid in Africa has been a controversial issue over the years, with economists like Dambisa Moyo even arguing against it, due to questions surfacing around its effectiveness in economic growth and poverty reduction.

A new research paper from Virginia Tech now delves deeper into this issue, noting that aid doesn’t even flow into poorer areas within countries. Looking at development projects commissioned by the World Bank and the African Development Bank across the African continent in 2009 and 2010, the paper shows that aid tended to flow to wealthier regions within nations, effectively undermining the goal of alleviating poverty in those areas. This spatial analysis shows the dichotomy between the delivery and effectiveness of aid and the levels of inequality that could exist between rural and urban regions.

In his paper published this month, Ryan C. Briggs, an assistant professor at the department of political science, shows that there are spatial differences in the degree to which aid reaches the poor in Africa. Briggs examined the data by dividing the African continent’s map—including North Africa and the islands—into 10,572 cells after which he aggregated aid projects, population, and poverty levels into each cell. After analyzing the data, areas receive more assistance he writes, “if they have more light, shorter travel times to major cities, shorter distances to the capital, and lower rates of child malnutrition.” This favoritism is not due to the fact that richer, more urban cells hold more people.

This goes against the norm of aid dispersion, which usually professes the goal of delivering education, healthcare, infrastructural projects, and more to poorer people or areas. But if aid is intended to reduce poverty, Briggs argues, “then it should be targeted to poverty according to the geographic scope of its anticipated effect.”

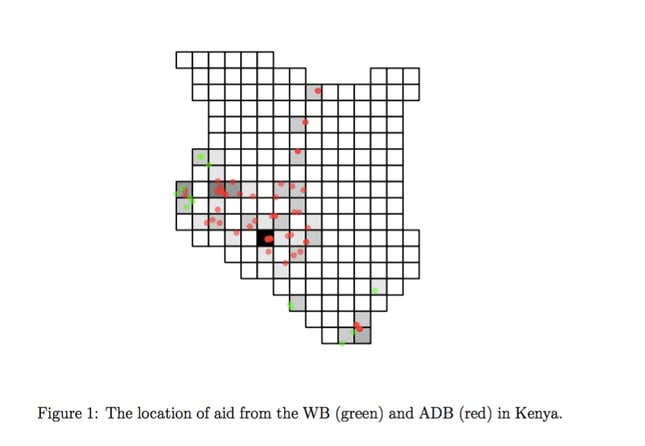

One example that illustrates this trend is Kenya, and how poorer provinces like the North or Northeast have many fewer projects than wealthier and more connected regions like Central and the Rift Valley. This landscape of inequality when it comes to financing projects or accessing resources in Kenya is an issue that has seeped into the political discourse in recent elections. These deep fissures in accessing finance have also helped augment sentiments about marginalization and ethnic animosity in the country.

Briggs says the fact that aid doesn’t specifically target the most vulnerable is “unfortunate” and means that they are less likely to benefit from projects hoping to boost national economic growth. The findings also show the predisposition to fund projects in urban spaces, hence increasing inequality in the long run. To end extreme poverty, African governments and donors will both need to seriously rethink how they approach aid dispersal and to invest in projects like roads that reduce the remoteness of the very poor.

“I think it is plausible that current aid allocations target richer areas because they can reach more people per aid dollar there,” Briggs told Quartz. But donors, he added, will have to “grapple with this unfortunate tradeoff” between “doing the most good per dollar and leaving no one behind.”