The trans pioneer who helped uncover how the brain is wired has died

Faced with a decision of choosing between identity and career, Ben Barres stuck to his identity. Lucky for everyone, he was able to keep both.

Faced with a decision of choosing between identity and career, Ben Barres stuck to his identity. Lucky for everyone, he was able to keep both.

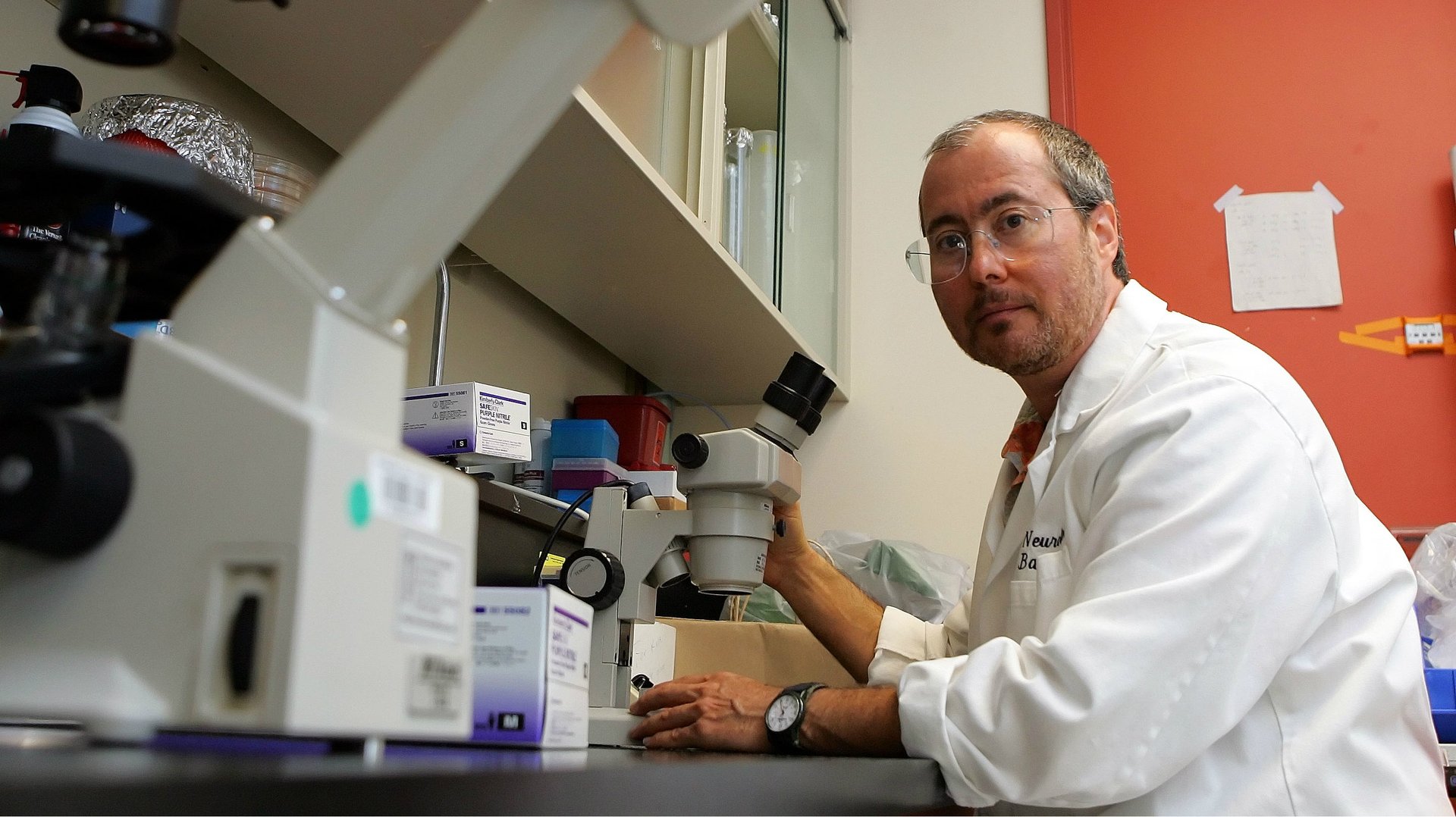

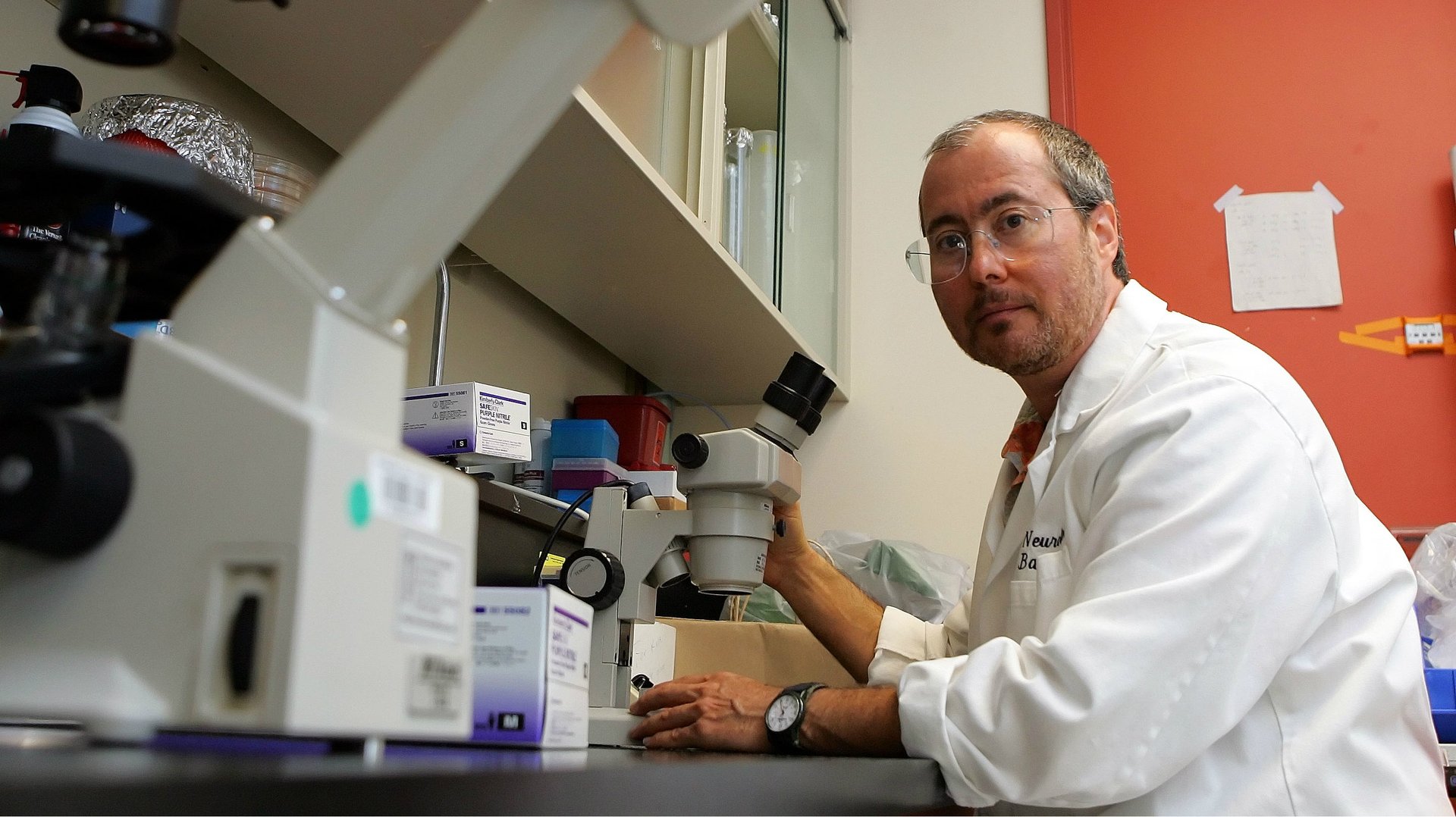

Despite facing adversity, Barres, a pioneering neurobiologist and transgender man, went on to produce groundbreaking research that helped explain how the human brain functions. During his decades in medical research, he ascended to the chairmanship of the neurobiology department at Stanford University’s School of Medicine and became the first transgender scientist to be selected for membership at the US National Academy of Science.

Barres died yesterday (Dec. 27), just 20 months after being diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, according to Stanford University. He was 63.

Opening up a new field of research

Much research had been focused on the network of nerve cells branching throughout the brain. Barres’ work focused primarily on glial cells, the brain matter that makes up just about everything else inside the skull. Once referred to as the mere “packing peanuts” of the brain, the “glia” were named after the Greek word for glue. Barres and his researchers through the years showed glial cells played a far more critical role than once thought—sustaining the architecture of the brain’s synapses and also helping the synapses send signals from one point to the next. Barres’ research showed that damaged glial cells may be to blame for some of the neurodegenerative diseases that continue to confound scientists.

Beyond his work in the laboratory, Barres was known as an outspoken supporter of marginalized minorities within academia. His life in the lab was shaped by his life outside it. Barres lived and worked under the name Barbara until his late 40s, when he transitioned. At the time, he described it as a choice between his identity and his career. He chose identity. He recalled how he was treated by the scientific community before and after his change for The New Republic in 2014:

“People who don’t know I am transgendered treat me with much more respect,” he says. He was more carefully listened to and his authority less frequently questioned. He stopped being interrupted in meetings. At one conference, another scientist said, “Ben gave a great seminar today—but then his work is so much better than his sister’s.” (The scientist didn’t know Ben and Barbara were the same person.)

In his lifetime, Barres published 167 peer-reviewed papers, laying the groundwork for the entire field of study around glial cells. Without him, colleagues have said, there would be no such field.

Inspired, and inspiring

“You know, I think science is beautiful,” Barres once said in an interview. “What is more beautiful than discovering something that has never been known before? That is sort of awe inspiring. Maybe that’s the same experience people get when they go to a museum and see a beautiful piece of art.”

Those were interesting words coming from a man who was face-blind. The actual condition he suffered from is known as prosopagnosia, which meant he was unable to enjoy art as most people do. He couldn’t distinguish people’s faces, which meant he relied on voices or other types of visual cues to recognize people, according to Stanford.

The university said Barres spent his last days and hours finishing letters of recommendation for his trainees.