The first time Nick Mullins entered Deep Mine 26, a coal mine in southwestern Virginia, the irony hit him hard. Once, his ancestors had owned the coal-seamed cavern that he was now descending into, his trainee miner hard-hat secure.

His people had settled the Clintwood and George’s Fork area, along the Appalachian edge of southern Virginia, in the early 17th century. Around the turn of the 1900s, smooth-talking land agents from back east swept through the area, coaxing mountain people into selling the rights to the ground beneath them for cheap. One of Mullins’ ancestors received 12 rifles and 13 hogs—one apiece for each of his children, plus a hog for himself—in exchange for the rights to land that has since produced billions of dollars worth of coal.

“I probably ended up mining a lot of that coal,” says Mullins, a broad-shouldered, bearded 38-year-old with an easy smile.

There were other ironies to savor too. Mullins was a fifth-generation coal miner. But growing up in the 1990s, his father and uncles—all of them miners—begged him not to get into coal mining.

“No one wanted to see you in the mines,” he says. “And they were all union miners too—had it good for a long time.” Those protections were gone by the time Mullins was growing up. The US government’s ongoing assault on organized labor through the 1980s and 1990s meant that the mammoth energy conglomerates that dominated the coal industry were free to open non-union mines with increasing impunity. But mining was still just as rough—replete with injuries, accidents, and black lung deaths.

During the coal bust in the 1990s, Mullins’ dad was laid off from Bethlehem Steel’s mines. Mullins recalls living off the green beans his family had diligently canned during the good times, and watching his parents grow desperate. Go to college, they urged him. Mining offered no future.

Mullins planned on following their advice. But he, like so many of his friends, family, and neighbors, soon found that the industry that has wreaked havoc on the economy of central Appalachia—composed of southwest Virginia, southern West Virginia, and eastern Kentucky—was also nearly impossible to escape.

Passing on the costs

Ask most Americans what they know about coal in central Appalachia, and they’ll tell you it’s a dying industry—one that US president Donald Trump famously vowed to revive during the 2016 election. “We’re going to put those miners back to work. We’re going to get those mines open … I see over here a sign, it says ‘Trump digs coal.’ It’s true. I do,” he told a rally in Charleston, West Virginia, in May 2016. “You’re going to be working your asses off.”

But the idea that the region’s coal industry is dying is not quite true. For much of the hundred-plus years of its existence, the industry has been on a kind of artificial life support, as state and federal governments have, directly and indirectly, subsidized coal companies to keep the industry afloat.

The costs of this subsidy aren’t tallied on corporate or government balance sheets. The destruction of central Appalachia’s economy, environment, social fabric and, ultimately, its people’s health is, in a sense, hidden. But they’re plain enough to see on a map. It could be lung cancer deaths you’re looking at, or diabetes mortality. Or try opioid overdoses. Poverty. Welfare dependency. Chart virtually any measure of human struggle, and there it will be, just right of center on a map of the US—a distinct blotch. This odd cluster is consistently one of America’s worst pockets of affliction.

At the root of these problems lies the ironic insight that struck Nick Mullins as he mined coal deep in the earth his family once owned. The extreme imbalance of land ownership in central Appalachia shifted the power over where and how Appalachians lived to corporations. The political and economic impotence of Appalachian residents that resulted has permitted a deeply cynical capitalist experiment to take place, in which coal companies are kept profitable by passing on the costs they incur to the public. The many ways in which politicians and coal barons have kept coal artificially cheap has, over the course of generations, devoured the potential of the area’s residents, and that of their economy.

Central Appalachia’s problems stem from its distinctive history. But the pattern of its struggles is not unique. Across America, obscure clusters of misery are growing in number and concentration—as people get sicker, poorer, and more isolated than they were just a few decades ago. Thus untangling the knotty problems of central Appalachia holds lessons for the rest of the country about how imbalances of wealth and power, created generations ago, can trap places and their people in the past.

The myth of coal jobs

The experiment underway in central Appalachia began with subsidizing coal by suppressing household wealth. To the local politicians who sponsored this strategy, the idea was that making conditions favorable to outside corporations would develop the local economy, creating jobs and enriching residents. How has that played out?

Not great, according to the most recent data from the Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC), the economic development partnership between federal, state, and local governments. Between 2011 and 2015, central Appalachia’s median household income was just over $34,000—around 63% of what the typical American household earned. Fewer than 60% of working-age adults had jobs or were looking for work, compared with 77.4% at the national level. At 8.6%, the unemployment rate in central Appalachians is 1.7 percentage points higher that of the US. Nearly a quarter of its residents were in poverty, compared with 15.5% nationwide. Even more remarkably, the region fares much worse on all these measures when compared to Appalachia as a whole, a span of country that reaches from eastern Mississippi to upstate New York.

Throughout the last 125 or so years, West Virginia’s economy and state budget has depended far more heavily on coal than Virginia and, to a lesser extent, Kentucky, making it a useful proxy for the socioeconomic trends associated with the region’s coal-reliance. Though coal was first officially spotted in central Appalachia in the 1700s, major commercial production began in earnest only in the 1870s, after railroads finally burrowed through dense, rolling heave of the Cumberland mountains. Output grew exponentially. By the late 1910s, West Virginia was producing around 90 million tons of coal, and employing nearly 100,000 miners. US Steel’s coal operation was West Virginia’s biggest employer.

How things have changed: After peaking in 1940, at 140,000—around a third of the state’s workforce—there are now only around 11,600 working miners in West Virginia. That’s the lowest number of coal miners the state has had since 1890, equal to less than 2% of its workforce. It’s very clear that coal has failed to create jobs. It is, however, still the only way that many West Virginians can earn a decent middle-class wage.

Nick Mullins’ story illustrates that paradox—and how decades of subsidizing coal profits over investment in human capital and technology has led to a dearth of opportunities for young central Appalachians.

Attending a high school so underfunded that many teachers paid out of pocket to make copies of handouts, Mullins made the National Honors Society. But in eighth grade, an administrator had talked him out of taking the advanced-track classes, telling him his course load looked like too much work for him to handle. Not that he needed much of a push—those classes were filled with the coal-boss kids, who bullied anyone whose dad actually entered a mine.

When Mullins asked his guidance counselor how to apply to college as a junior, she told him that, without having taken advanced classes, it was pointless. For the next few years, he bounced from southern Indiana to Knoxville and back to Virginia in search of a decent living, taking whatever work he could find—a Christmas temp gig in Wal-Mart’s layaway department, carpentry jobs, night stockman at a grocery store, a janitor at a chemotherapy complex, clerk at Magic Mart. Nine jobs later, he finally caught a break, landing an $18,000-a-year technician position at a call center just opened by Crutchfield, a catalog and online consumer electronics retailer. After seven years, he was earning nearly $30,000. But with two kids now, and health care costs at $300 a month, he and his wife had nothing left each month to save.

As a trainee coal miner, Mullins could earn what he was making at Crutchfield—but with better health benefits and a retirement plan with matching. Despite the ebbing of union clout, coal jobs still offered a level of economic security unheard of in other industries. There really wasn’t much choice to be made; just his family’s fears to push aside.

Mullins talked himself into what he calls coal’s “cult of self-worth,” built around following his forbearers into hard, dangerous work. “I wanted to be a proud, self-sacrificing guy who works two miles underground, where most people won’t go, to provide for my family,” he says. Whenever he went into town, he made sure his “Deep Mine 26” ballcap was pulled snug over his head.

Coal’s dominion has receded in West Virginia. Why, then, could Mullins find no well-paying work in central Appalachia except mining? Why has the structure of the central Appalachian economy changed so little?

Henry Hatfield’s lament

Nearly 100 years ago, Henry Hatfield, who became the governor of West Virginia in 1913, predicted this contemporary dilemma. At the time, West Virginia was producing nearly 70 million tons of coal—a roughly 30-fold increase from 30 years prior. Coal was making West Virginia rich.

But Hatfield saw trouble ahead.

“Rich as we are as West Virginians in our natural resources,” he said in his March 1913 inaugural address, “more than 80% of our fuel and raw material is utilized outside the state.” As a result, he said, low prices fixed “a standard of wages for the miner that is an injustice to him, by reason of the long railroad haul to market.”

Indeed, coal operators “extracted more work at less pay from mountain miners, and this substantially lowered their cost of production,” writes historian Ronald Eller, professor emeritus at University of Kentucky, in his book, Miners, Millhands and Mountaineers.

The coalmine owners were able to do this because central Appalachian miners were mostly nonunion, unlike their fellow miners in Pennsylvania or the Midwest. “In those days, competition almost universally took the form of competitive wage cutting,” wrote statistician Isador Lubin, the head of the US Bureau of Labor Statistics under president Franklin Roosevelt, in his 1928 book Wages and Cost of Coal. “The operator sold his men rather than his coal.” The resulting boost to profitability “has tended to increase the development of the nonunion fields more rapidly than the country required.”

Governor Hatfield dreamed that his state’s endowment of coal would lead to local investment, fuelling factories, and enriching its economy. Instead, its resource wealth chugged out of the state by the train-load, along with the profits it generated.

West Virginia produced a lot. But it manufactured almost nothing. And that’s still the case. Whereas US Steel once employed droves of West Virginians to gouge coal from inside mountains, for the last two decades, Wal-Mart has usually claimed the title of the state’s biggest employer.

Since Adam Smith published his magnum opus The Wealth of Nations, capitalist societies have taken as faith that the key to prosperity is specializing in what they’re naturally good at. Central Appalachia’s economy seems to rest firmly on this logic. It has some of the finest-quality coal on the planet, and so it has sought to specialize in selling coal. Why, then, is it so much poorer in both wealth and well-being than the rest of the US?

Perhaps our assumptions about the scale of “specialization” are too simplistic. A new field of research by Cesar A. Hidalgo, a statistical physicist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Media Lab, and Ricardo Hausmann, an economist at Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government, has begun probing that possibility by measuring areas’ “economic complexity”—the mix of products a country makes. It turns out that places with less economic complexity tend to grow more slowly and have much bigger gaps between rich and poor, even after taking into account factors like income and education levels.

Why is economic complexity good? For one thing, the complexity and diversity of products made in a region tend to be a proxy for the knowledge and know-how of its workforce. This makes workers more valuable and gives them a broader range of career options, upping their bargaining power. By contrast, countries—or regions like Central Appalachia—that make relatively few things tend to constrain people’s opportunities to learn new skills, whether on the job or at school.

The curse of weak institutions

Economic complexity illuminates one dimension of central Appalachia’s struggles. Another source of insight comes from research by Daron Acemoglu, an MIT economist. In Why Nations Fail, which he co-wrote with University of Chicago political scientist James A. Robinson, the duo explore why some resource-rich nations are rich while others remain poor. They argue that the fate of a nation is determined in large part by its economic institutions—its financial systems, tax regimes, property rights laws, labor institutions, and markets, among other things.

When economic institutions are inclusive, they level the playing field among businesses, create competitive markets, encourage investment in new technologies, and enable people to acquire skills to pursue their talents, according to Acemoglu and Robinson. The institutions are underpinned by a political system that empowers a broad base of citizens to influence political decisions, preventing a single interest group from holding sway.

Extractive institutions, on the other hand, concentrate power among the few. This structure encourages the elite to warp institutions to enrich themselves and their political allies, which tightens their stranglehold on institutions all the more. “Different patterns of institutions today are deeply rooted in the past because once society gets organized in a particular way, this tends to persist,” Acemoglu and Robinson write. While inclusive institutions drive “virtuous circles” of self-perpetuation, extractive ones fuel “vicious circles.”

Natural resource wealth can amplify these dynamics. Places with weak institutions—Algeria or Nigeria, for instance—typically succumb to the “resource curse.” Those with strong institutions, like the UK or Norway, tend to distribute that wealth more broadly.

The destructiveness of extractive institutions can be hard to discern when times are good. Even though wealth is unequally distributed, the majority of people tend to be buoyed by economic growth. The real trouble arises when growth falters. Instead of letting new sectors emerge to replace the struggling ones, the elite protect the old guard, a key source of their power and wealth. This thwarts creative destruction—the concept pioneered by economist Joseph Schumpeter to describe how the failure of inefficient enterprises frees up resources for more productive firms.

Though central Appalachia isn’t a sovereign state, Acemoglu says that his and Robinson’s framework applies to the region’s long-run problems. He points to research done by economist Robert Tamura, of Clemson University, on the long-lasting effects of slavery on the economic development of the American South, as well as to analysis by Melissa Dell, a Harvard University economist, that shows how areas of Peru and Bolivia subjected to forced mining labor systems in the 16th through 19th centuries currently suffer from lower education levels and investment in public goods and services.

The vicious circles cementing central Appalachia’s extractive institutions don’t go back that far. But they do predate the region’s coal boom by a century.

Land bonanza

Why has the coal industry been permitted so much free rein over central Appalachia, despite the obvious toll it has taken on Appalachian residents? For one thing, the people responsible for devastating the area don’t actually have to live there and experience the consequences of their actions. By the time America won its independence, central Appalachia had already been carved into estates owned from afar.

The British crown and colonial authorities granted huge tracts to court favorites, Virginia planters, and eastern capitalists, according to historian Wilma Dunaway’s book, The First American Frontier. From there, land accumulation by distant capitalists snowballed. In the 1790s, Virginia—followed by Kentucky—began selling cheap warrants for frontier land. By 1810, absentee investors owned around 93% of what’s now West Virginia and at least three-quarters of eastern Kentucky, according to Dunaway.

It wasn’t just far-flung fat cats cashing in. Local merchants, lawyers, judges, and politicians also snapped up land. Largely through control of state governments, this homegrown political and business aristocracy bent policy to enhance that land’s value, says historian Lou Martin, history professor at Chatham University in Pittsburgh. “Central Appalachian states were anxious to get outside investment and took steps to protect capital, making taxes more favorable to large companies,” he says.

After the railroads finally bore through central Appalachia’s mountains, in the late 1800s, the coal industry followed a similar development path. At first, smaller coal operators abounded. But by the early 1900s, big, out-of-state companies gobbled up small, locally-owned companies, according to Eller, the University of Kentucky historian.

We typically think of “wealth redistribution” as shorthand for taxing corporations and the wealthy to give money to the poor. Central Appalachia’s extractive institutions allowed exactly the reverse—for the region’s natural wealth to be redistributed to shareholders in faraway metropolises, and in a sense, to America’s emerging middle-class consumers who benefited from artificially cheap energy, at the expense of ordinary Appalachians.

Typically, tax policy would be used to offset the profiteering of absentee corporations. Not in central Appalachia. In 1902, West Virginia’s state tax commission observed that coal “is being mined from and transported beyond the State, and continuously subtracted from the State’s property values without paying to the State one cent of tribute.” The report’s author warned that “when wholly exhausted, nothing but a comparatively worthless shell will be left behind… the kernel having been removed without the requirement of contribution to the State’s support.”

Had West Virginia moved to change its tax system, it might have used coal companies’ taxes to fund public investments that could have given residents more economic freedom and better quality of life. But supporters of the extractive regime were vastly more powerful. Political bosses often doubled as coal operators, and “company men” were frequently elected to state senate, typically serving as head of the mines and mining committee. Through the vast tentacles of its influence, the coal lobby tied up lawmakers’ efforts to tax coal and pass mine safety laws, despite persistent efforts by Progressive politicians. Only in the 1970s did states pass laws that claimed any share of the earnings on coal extraction on behalf of their citizens.

But even with plum tax laws, central Appalachia’s remote coalfields still couldn’t easily compete with the coal mined in Pennsylvania, Indiana, Illinois and elsewhere. To compete—and to reap profit—companies made their coal cheaper not only by suppressing miners’ pay, but also their purchasing power and, therefore, their standard of living.

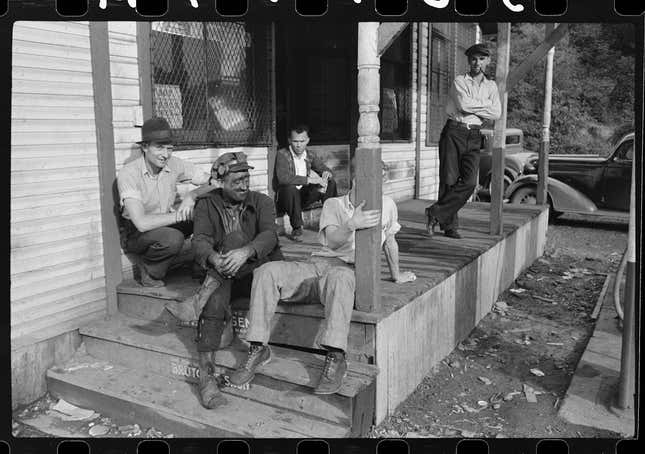

As demand for central Appalachian coal boomed in the late 1800s and early 1900s, displaced farmers and landless sons filled the new ranks of wage laborers entering the mines. To supplement their ranks, companies—sometimes using coercive tactics—recruited poor workers from the American South and even Europe. The region’s population exploded.

With few existing settlements to house this new laboring class, the vast majority was housed in coal camps. A Senate report found that around four-fifths of West Virginia miners lived in company-owned coal camps, and more than two-thirds of Kentucky miners, according to Eller. That compares with 9% of miners in Indiana and Illinois.

This wasn’t normal small-town America, or even something resembling other “company towns” around the country. All of these were privately-owned, privately-governed communities designed to give the mining companies maximum control not merely over mineral resources—but over human ones too.

Nada White’s story

Nada White witnessed the power of the coal camps firsthand. Now in her late 60s, White is a medical assistant who lives with her son, Dustin, outside Charleston, the capital of West Virginia. Her early girlhood was spent with her parents on a farm in the family hollow, tucked up against the belly of Cook Mountain, in southern West Virginia, where ten generations of Cooks had grown up.

Those early days were spent swinging on mountain vines, collecting mollymoochee mushrooms in the spring, and picnicking in the glade where all the Cooks before her were buried. Then it came time to go to school, which was two hours away, longer in winter. However, the school bus came right to Wharton, a tiny town a few miles away, where her grandparents lived. So White moved in with them.

Back in the 1950s, her granddad did the same thing as all the other men in Wharton: he mined coal for Eastern Gas and Fuel. And like all the others, the Cooks’ lived in one of the 50 or so houses that sat in a double row near the mouth of the hole in the hillside into which White’s grandpa disappeared each day to gouge coal from the guts of the mountain.

Just as it had powered America’s staggeringly swift industrialization during the previous 50 years, the tar-black ore that came out was now fueling America’s postwar boom. At the edges of Appalachia, mighty factories churned out steel to make Fords and Chevys. The coal needed to smelt that steel came from Wharton and elsewhere in Boone County and throughout the central Appalachian region—as did much of the coal burned to power industry and the new Frigidaires and television sets filling the homes of America’s burgeoning middle class.

The people of Wharton and other coal towns weren’t part of this mass-consumption metamorphosis, however. One problem with town planning by plutocracy is that the coal camps suffered the ugliness of industrialization—disease, squalor, poverty. But it did not experience the benefits of a diversified economy and public services that typically accompany industrialization—affordable transportation, easy access to food and markets, job opportunities, newspapers, recreation.

Since they were privately owned, the camps enabled mining companies to govern not only production, but services and all means of consumption too: retail, recreation, education, medical care, worship, you name it. Each town was its own mini-monopoly—a phenomenon embodied in the company store.

Flouting state laws, mine operators forbade miners from shopping anywhere beside the company store. White’s grandfather and the others didn’t even earn the same kind of legal tender as factory workers in Pittsburgh and Toledo. He and the other miners were paid in little metal tokens notched in the middle and stamped with the Eastern logo. Scrip, it was called—and it could only be used in one place: the company store.

On payday, White’s grandpa filed with everyone else into the Eastern company store to pocket a little mound of scrip, most of which he’d hand right back to pay for pinto beans, potatoes, rent, coal for home-heating, and any replacement mining gear he needed. (Workers supplied their own.) “Mostly you spent all your money on pinto beans and hoped your fridge didn’t break,” says White. The scrip system worked because there were no other stores. “There was just nowhere else to go.”

Up and down the Chesapeake & Ohio rail line that rattled through Wharton two or three times a day were plenty of other small settlements—Robinhood, Twilight, Greenwood, Prenter. Each had its own company store too, but they wouldn’t take Eastern’s scrip. Those took only the scrip of Bethlehem Steel or Armco or whatever other coal company owned the town. And they were all overpriced.

“They could charge double or triple the price because they knew you had to come to the company store,” says White.

“The greatest drain on the miners’ wages was the company store,” explained historian David Alan Corbin in Life, Work, and Rebellion in the Coal Fields. “Coercion, the scrip system, and the physical distance often combined to force the miners to deal at the company store, and through the monopolistic control of food and clothing and tools and powder, the coal companies were able to render wage rates and wage increases meaningless.”

Ordering from the catalogues of Montgomery Ward or Sears was much cheaper than the company store. That’s where White’s family got new shoes for school. But raising hard cash was tricky. The few folks with family tending farms in the hollows, like White’s, sold chickens or eggs to raise money—or hogs when times got really tough. In the winter, White’s dad also earned cash by driving coal around in his pickup, delivering it to families that needed it for heat (which few coal companies provided). Most people didn’t have pickup trucks or chickens, though. This made it easy to fall into debt, which many of White’s friends’ families did.

There were other dangerous dependencies that were simply facts of life in Wharton. White recalls the day the four company men marched into the house next door, where Fred and Bobbie York lived, emptied all their things into the small soot-specked yard, and left. It was threatening to rain, and there sat Bobbie’s piano. White, her grandmother, and Bobbie hauled it up onto the Cooks’ porch, just missing the downpour. The Yorks gathered their damp belongings into a borrowed car and left. A week later, a new miner and his family moved in. White learned later that Fred’s leg had been badly broken in the mines and Eastern was fed up waiting for it to heal. After a while, someone came for Bobbie’s piano. Where the person took it, or what became of the Yorks, White never heard.

The company could do that, of course, because Eastern owned the Yorks’ house. They owned everyone’s house, in fact—and everything else in Wharton from the church to the clinic, except the post office. There was no other employer. Those who complained found themselves not only jobless but blackballed, leaving them nowhere to work or live.

People kept themselves in line, and quiet, says White. “You didn’t want to talk bad against them—our whole existence depended on the coal companies.”

For hundreds of miles in any direction, almost all of the towns were privately owned, privately operated settlements almost all owned by companies like Eastern. There was only the faintest hint of public services—or, even, for that matter, representative government.

Mind you, by the 1950s, coal camps were comparatively comfortable compared to what they’d been like before the 1930s, when the passage of the National Labor Relations Act granted central Appalachian miners the right to organize.

In the early decades of the 1900s, because coal companies owned most of central Appalachia’s towns, “mine guards”—essentially private paramilitary forces—policed the region. These forces were broadly supported by the West Virginia government, which declared martial law four times in the early 1900s to put down miner strikes. (Facing a worker revolt that saw thousands of miners join together to oust a particularly brutal sheriff in Logan County, the governor went so far as to dispatch bomber planes.) Thanks to this system, southern West Virginia was home to some of the bloodiest fights in the history of America’s labor movement.

To put it most simply, coal camps were economic institutions built to deny people agency. Of course, miners weren’t slaves. But there were parallels. In a 1920s US Senate hearing, a Logan County miner named George Echols who had been fired for heading up the local union explained the combination of chronic underpayment, coercion, and violence prevalent in the coal camps. “I was raised a slave [in antebellum Virginia],” he told the committee. “My master and my mistress called me and I answered, and I know the time when I was a slave and I felt just like we feel now.”

Much has changed since the 1950s. As federal labor laws improved the job security and wages of miners, rising electricity demand in the 1960s pulled the coal industry out of a postwar lull. Soaring oil prices resulting from the formation of OPEC a decade later spurred another coal boom.

At the same time, a lot hasn’t changed at all.

The legacy of coal camps

“A manufacturing town may count upon a reasonable degree of permanency. A mining town in a region not suited to other industry is sure to have only a limited life,” a 1923 Congressional report investigating coal-camp life explained. “It is this feature that differentiates the company-owned mining community from the company-owned manufacturing community.”

That fatalistic approach to community planning seems to have played out in the coalfields. Through the coal slump of the 1950s and early 1960s, companies razed thousands of coal camp homes to cut their tax burden. Though some companies sold their land holdings, it was often to other big companies—not residents. Others continued charging existing occupants rent, refusing to sell. “I could go up and offer $100,000 for this house and they’d laugh in my face, even if I had it in $100 bills,” a mine safety inspector living in a Logan County company house—whose roof had a gaping hole—told ARC in the late 1970s.

“For many Appalachian people, coal camp life is not a bygone era,” said the 1980 ARC report. “Facing no alternative, people remain, often dependent upon the will and wishes of the company landlord. In staying, they face insecurities of tenure, dilapidated housing, and fear of the company’s power.”

As of 2013, of the 10 largest landowners in West Virginia, none is headquartered in the state, according to a 2013 study by historian Lou Martin and economists at the West Virginia Center on Budget and Policy. In six counties, the top ten landowners control at least half of private land. Five of those six—Mingo, Boone, Logan, Wyoming, and McDowell—are in the central Appalachian coalfields.

The political power of coal hasn’t faded either. As it happens, Jim Justice—who in 2016 ran and won West Virginia’s governorship on the same “bring back coal jobs” promise as Trump—is also the state’s sole billionaire, and one of its bigger landlords. At the time the WVCBP study was conducted, Justice owned 2% of McDowell County, as well as 2% of Greenbrier and 3% of Monroe counties. He also boasts a fortune invested in several Kentucky coal mines, timberlands in West Virginia, and a resort that has catered to coal barons for more than a century (and now fetes the New Orleans Saints).

This pattern of land ownership and extractive institutions, the legacy of policies set centuries ago—set the stage for a new way of passing on the costs of cheap coal to the public.

The tragedy of Buffalo Creek

Much of the mining in central Appalachia wouldn’t be profitable if companies shouldered the true costs of this environmental blighting. Instead, companies pass those costs on to the public.

For one, there are the costs to human safety. Strip-mining and mountaintop removal have been linked with cataclysmic floods that, a few times a decade, destroy tens and even hundreds of millions of dollars in property. The worst floods have killed dozens or even scores of residents.

Though few today have heard of it, one of the ghastliest industrial disasters in US history took place in a coal camp-specked hollow in Logan County called Buffalo Creek. One rainy February morning in 1972, a dam holding 157 million gallons of coal waste gave out, sending a 15- to 20-foot tsunami of black gunk ripping through the hollow, according to Everything in Its Path, a study of the disaster by Kai Erikson, a Yale sociologist. The flood killed 125 people, damaging around $50 million in property (about $300 million in current dollars) and leaving four-fifths of residents homeless.

Pittston Coal Company—a Virginia-based company that owned the dam—claimed the dam’s sole problem was that it was “incapable of holding the water God poured into it.” But earthlier explanations exist. Raw coal must be bathed of impurities before being burned. Each day, Pittston’s Buffalo Creek mines produced around 4,000 tons of market-ready coal and 1,000 tons of refuse. From the refuse, Pittston built dams to hold the 500,000 gallons of coal-dirtied water it ran through each day—an engineering feat that Appalachian writer Harry Caudill likened to “a pool of gravy in a mound of mashed potatoes.”

Though the federal government had in 1969 outlawed this particular type of impoundment, state officials ignored both the law and local residents’ complaints about the dam’s shoddy state.

Pittston did eventually foot some of the bill for the Buffalo Creek disaster, settling a class-action lawsuit from residents for a total of $13.5 million (about $13,000 per person). The state sued Pittston for $100 million, half of which was to cover cleanup and damages. Then the extractive institutions swung into action. In 1977, then-governor Arch Moore settled with Pittston, accepting $1 million—less than a fifth of what West Virginia taxpayers spent on cleanup.

Moore wasn’t alone in helping keep coal operators profitable in the face of soaring environmental costs—particularly as the easy-to-reach underground seams tapped out, and companies turned to strip-mining. States had passed laws overseeing strip-mining; however, these were so toothless and little enforced, notes Eller, that in both Kentucky and West Virginia, the practice increased after those laws’ passage.

In 1977, the federal government finally weighed in. Paradoxically, though, the new law created an above-board way of shifting the astronomical costs of mountaintop removal’s destruction onto taxpayers, with a devastating impact on the lives of central Appalachians.

The Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act was supposed to require that mined land be restored to something approximating its original shape. However, a loophole in the law let coal companies ignore that expensive requirement if the reclaimed land could be put to “a higher and better use.”

Coal companies instantly saw their opportunity, as Ron Eller recounts in his modern history of Appalachia, Uneven Ground. What if the now-flattened mountaintops they were creating could be pitched to government officials as a way to attract outside factories and create more jobs?

Higher and better use

Almost overnight, strip-mining underwent a hypertrophic mutation, as mining companies turned to blowing up mountain peaks and deploying hulking, 20-story machines to claw open coal seams below, replacing verdant ridges with moonscape mesas of lifelessness.

The land area of southern West Virginia scarred by active mountaintop removal leapt more than threefold between 1985 and 2005 and has stayed steady since then, according to GIS analysis by SkyTruth, an environmental nonprofit. As of 2015, some 8% of Boone County was being actively mined, compared with 2% in 1985. Today, the biggest mine sites exceed the island of Manhattan in size. It is impossible to restore the land to its former state. And the new law made it so they didn’t have to try. A recent Duke University study found that coal companies had left the area they studied 40% flatter.

The scale of environmental carnage is possible, at least in part, because of the land-grab legacy: corporate control of enormous land parcels has meant residents lack the legal clout to object. It’s also been possible thanks to the signing away of mineral rights that happened in the late 1800s and early 1900s—that saw Nick Mullins’ ancestor part with a hoard of coal wealth for 12 rifles and 13 hogs. This wasn’t merely a matter of swindling farmers out of subsurface riches. Since mineral rights legally trumped surface rights, corporate ownership let coal companies clear cut forests for mine supports, build roads and railroad spurs, pollute and divert streams—all without having to pay taxes on the land they defaced, as Erikson explains. Strip-mining, however, pushed this bait-and-switch to a whole new level. Mineral rights let coal companies tear off mountaintops—ruining the land permanently—to get at the coal beneath it.

Then there are the costs that come with trying to find some higher and better use. Desperate to show they’re creating jobs, local politicians have spent many millions in taxpayer funds recruiting out-of-state factories to the “flat land” created by mountaintop removal, according to Eller. Few have panned out. The region’s manufacturing sector was about the same in 1992 as it was in 1967, according to a study commissioned by ARC. It still suffered from low wages, low productivity and over-reliance on branch plants. Meanwhile, a super-max penitentiary built atop a leveled mountain in Virginia struggles with a cracked foundation (the locals dubbed it “Sink-Sink”). Mingo County recently unveiled a new airport on one such dusty tableland; its major industrial park, which sits on a former mine site, remains mostly empty.

“There are lots more mountaintop removal sites than there ever will be airports or shopping centers,” says Peter Hille, head of Mountain Association for Community Economic Development, or MACED, an economic development group in Kentucky. “Most of these sites are in places where it doesn’t make any sense to build anything. Coal creates economic activity for a period of time but not development. It creates employment for some, wealth for a few, and sucks oxygen out of the room for the other people.”

This spending might temporarily boost the area’s GDP. But in the long run, that money isn’t being spent on self-sustaining investments in upping the skills and knowledge of local workers and businesses. Lou Martin, the Chatham University historian, notes, “You can still see state governments worried about losing jobs and trying to help corporations, at times at the expense of employees and residents.”

The false promise of more jobs

Despite the state support it’s enjoyed, the shift to mountaintop removal hasn’t created much in the way of jobs. They require far less labor than underground mines. For instance, coal employment in West Virginia fell by three-fifths between 1983 and 2000; 94% of those lost jobs were underground, according to research by Downstream Strategies, an environmental consulting group.

Nowadays, taxpayers subsidize the coal industry directly too. In fiscal year 2009, West Virginians paid a net $42.2 million to support coal companies, according to a study (pdf) by WVCBP and Downstream Strategies, an environmental consulting firm. The report noted that “this value fails to capture the significant legacy costs resulting from past coal industry activity that have yet to be funded. These costs, which include damages to roads and bridges and funding needs for reclaiming all abandoned mine land and bond forfeiture coal mine sites in the state, amount to nearly $5 billion.”

Even those data ignore the human toll, however.

As it happens, that is what finally convinced Mullins to leave coal mining behind. In the mid-2000s, a freak fire burned down his home. He and his family lost everything. But they gained a modest homeowners insurance check and some good advice—that maybe they should see the fire as an opportunity instead of a tragedy.

“My brother put it to me: ‘Do you want to be a coal miner for the rest of your life?’” says Mullins. “All these things started weighing on me—I had a few run-ins with some of the management that month and realized exactly where we stood as people, as human beings, to the mining company. And I saw how they pitted us against each other and realized I couldn’t stay on that path.”

It took him about a month to quit his mining job. A year later, he and his family moved just outside of central Appalachian Kentucky, where he attended Berea College and finally got his degree. He now runs his own public relations firm aimed at bridging political and cultural divides surrounding Appalachian issues.

Greater economic opportunity was part of why they left. His biggest concern about staying, however, was their two kids. Eroded by dwindling budgets, local schools were even worse than when Mullins had attended them. He worried about his kids’ health, too. Mountaintop removal sites and underground mines engirdle Clintwood, creating untold volumes of toxic waste buried in unnamed patches of ground. The backyard creek that ran past his house did so increasingly in Technicolor hues. That impetus to leave gained new urgency, however, when a public health scientist named Michael Hendryx began publishing his research.

Dark waters

Blowing off a mountaintop releases naturally occurring poisons like arsenic, selenium, lead, and manganese. These poisons then seep into streams and groundwater. Meanwhile, the blasting fogs the air with a toxic cocktail of dust that settles on roofs and windows in the valleys below, and cakes the lining of lungs. The displaced soil and vegetation from mountaintop removal is plowed into valleys, creating enormous detritus piles and choking off waterways.

Between 1985 and 2001, mining operations buried some 724 miles of rivers and streams, according to the EPA. And since 2002—when the George W. Bush administration redefined “fill material” in the Clean Water Act to include mining waste—the rubble plugging up central Appalachian waterways is laced with toxic muck.

For a decade now, peer-reviewed research produced by Hendryx, now a professor of applied health science at Indiana University, exposed a consistent link between mountaintop removal and a broad range of health problems and rising mortality rates. According to his research, since 1990—when amendments to the US Clean Air Act inadvertently stoked the growth of mountaintop removal (registration required)—parts of central Appalachia with mountaintop removal have had about 1,200 extra deaths per year, adjusting for age, smoking habits, and other factors.

In addition to all-cause mortality, self-reported rates of some forms of cancer and mortality from diseases of the heart, lung, and kidneys are significantly higher in places with mountaintop removal, compared with places in Appalachia where it doesn’t occur—even when adjusted for age, gender, smoking, work and family history. Rates of birth defects are 26% higher in areas with mountaintop removal than in the non-mining regions of central Appalachia. These findings are ominous because birth defect rates are unusually sensitive to exposure to toxic chemicals, even though the specific mechanisms are little understood.

Though it’s hard to put a dollar sign on the human toll, Hendryx estimates that costs associated with the higher mortality of Appalachia’s coal-mining regions between 1979 and 2005 totaled $50 billion a year (in 2005 dollars), compared with the $8 billion contributed by the coal industry in 2005. A 2011 study (registration required) put the health, environment, and other economic costs of coal-fired electricity at $345 billion, and possibly more than $500 billion, doubling—and possibly tripling—the costs of coal-generated electricity. “These and the more difficult to quantify externalities are borne by the general public,” they write.

Despite the data, the effect of mountaintop removal on people’s health remains a topic of much debate. The coal companies, unsurprisingly, dismiss Hendryx’s research, as do a long roster of West Virginia politicians. Instead, you often hear that central Appalachians are sick because they’re poor and because they make bad choices.

This is the way America commonly understands ill health and early death: that it’s a matter of cigarette drags, cheeseburger bites, and other spasms of feeble character. It’s true that, because towns were developed based on their proximity to coal mines rather than commercial centers, residential communities are often more than an hour’s drive from grocery stores. Gas stop fare of buffalo wings and pepperoni rolls are the quick meal options available to most.

But part of coal’s legacy in central Appalachia is that, as with their economic opportunities, individuals often don’t have much control over whether they are healthy or not. Between drugs, poverty, social isolation, and lack of educational opportunities, there is any number of hazards that can derail, or even end, a person’s life. With so many possible pitfalls, it’s difficult to avoid encountering some.

The media and lawmakers are increasingly drawing connections between economic stagnation and destructive behaviors like opioid abuse and other “deaths of despair”—a term coined by Monnat and popularized by Nobel laureate economist Angus Deaton, which includes suicide and alcohol-associated liver disease as well as drug overdoses. And economically battered central Appalachia leads the pack. In 1999, rates of these “deaths of despair” among those aged 15-64 were the same inside and outside Appalachia, according to a recent report commissioned by ARC. By 2015, the combined mortality rate from these deaths was nearly 95 per 100,000 in central Appalachia, versus 49 per 100,000 in non-Appalachian US.

That’s appalling, of course—but what might be even more disturbing is the larger context of that disparity. It’s not just that central Appalachians are doing worse with opioids than everyone else. They’re dying at higher rates from other causes too.

Though mortality rates for most major causes of death have improved in the region since the late 1990s, they’re still far higher than the rest of the country. Between 2008 and 2014, heart disease—the leading cause of death in the US—killed nearly 250 people per 100,000 in central Appalachia, 42% higher than the rest of the nation, according to ARC research. Cancer claimed 222 lives per 100,000 in the region, around a third more than the US as a whole. Rates for chronic pulmonary obstructive disease exceeded national rates by more than 80%; diabetes deaths were 40% higher.

They’re also dying younger. Between 2011 and 2013, the nation averaged 6,658 “years of potential life lost”—the cumulative number of years a region loses per 100,000 people when its residents die before reaching age of 75, according to ARC. Central Appalachia lost 11,226 years of potential life.

But the words typed on a death certificate don’t tell us much about the quality of people’s lives. Central Appalachian residents also have higher rates of disability and chronic disease (pdf, p.86).

This may have something to do with the economic precariousness that is a fact of life in central Appalachia. A growing body of scientific evidence links “allostatic load”—basically, chronic wear and tear on the body caused by repeated triggering of stress hormones—with chronic disease and premature death. Many of the maladies strongly associated with allostatic load are problems in central Appalachia, such as diabetes, obesity, and heart disease. Allostatic load is also linked to depression and impaired mental functioning. Some scientists hypothesize that the system’s inability to balance its brain chemistry caused by chronic stress may also encourage addiction.

Central Appalachia’s brutally low living standards certainly bring with them plenty of stress. And the economic realities of the region mean that a sense of community, which might alleviate the effects of stress, is hard to come by.

Marlene Spaulding’s story

Marlene Spaulding grew up in a Kentucky town called Beauty during the 1970s. “I’m not really sure there’s a whole lot of beautiful there,” she says.

The town was once known as Himlerville—the home of the first cooperative coal-mining company in the country. Founded in 1917 by Hungarian immigrants, each employee in Himler Coal Company owned company stock and received a share of its profits, according to Eller’s Miners, Millhands, and Mountaineers. The houses in Himlerville were nice. Each had two fireplaces, gas and electricity, a tub and shower, and a vegetable garden, among other amenities. Miners could choose to buy their home or even build their own. Himlerville had a library, an auditorium, a modern school open 10 months out of the year, a local newspaper, as well as commercial developments that included a bank, a hotel and a bake shop. Miners elected by their fellow employees sat on the company’s board of directors.

The company and the town prospered throughout most of the 1920s. But in 1928, private capitalists bought its assets. They renamed it Beauty a few years later.

By the time Spaulding was growing up in the town, life in Beauty was hard. Her biological mother was 14 when she gave birth to Spaulding and her twin sister, and a local family adopted the girls. Her adoptive mom came from a family with 18 children, her adoptive dad had 12 siblings. By her count, there are only two members of her extended family who have never been to prison.

Drugs were a big problem. Spaulding’s older brother got hooked in high school, and was in prison before long. Back then, they let prisoners out on furlough over the weekends. Her brother would usually run off with his friends. Spaulding recalls awakening one night to her mom calming her as policemen filed into her room to search for her brother under her bed. “And that was normal to us,” she says.

After a life spent shuttling in and out of prison, her brother died of cancer when he was 48. Six weeks before he died, police busted him for selling morphine “off his deathbed,” as Spaulding puts it, most likely to exchange for something stronger. “One of the hardest parts about him is I really can’t name anything good he did in his life,” she says. “He never carried a job, never had a contributing role in society, was never a productive person.”

But her childhood could have been much worse. As an adult, Spaulding tracked down a biological sister who had been born three years after Spaulding but hadn’t been adopted. The two met up at the local Dairy Queen, where she learned that her biological sister had drug problems and was essentially homeless. At that moment, she happened to live eerily close by—beneath a bridge on the Tug River that Spaulding could see from her office window. “That very easily could have been me,” says Spaulding.

Long before the rest of the nation noticed, the opioid crisis took root in central Appalachia. By 2015, West Virginia’s rate of opioid-related overdose death for those aged 15-64 was more than three times higher than the non-Appalachian US, while Appalachian Kentucky’s was more than twice the rate. McDowell County, in West Virignia’s southern coalfields, has the highest opioid overdose rate in the country.

It’s probably no coincidence that coal-mining towns emerged in the 1990s as the epicenter of the opioid crisis, says Shannon Monnat, sociology professor at Penn State University. Of course, injuries abound and surgery is common, leading to prescriptions for heavy-duty painkillers. To keep injured miners working—and from claiming disability insurance—some companies had doctors prescribing pain drugs on the job.

It’s not just miners who rely on painkillers. Ask central Appalachian residents about addiction, and people will just as casually mention waitresses or hospital workers who dose themselves to keep their jobs. The 2008 ARC study reported that in coal country, women, unemployed people, and those whose households earned less than $35,000 a year were more likely to be admitted for substance abuse treatment in the coalfields than in other parts of Appalachia.

Part of the problem may be that high unemployment levels create a ready workforce of traffickers. Central Appalachians themselves will tell you that boredom has a lot to do with it: In a place where movie theaters, restaurants and skating rinks have mostly shuttered, recreational drug use doesn’t have much to compete with.

Spaulding escaped opioids, but not teen pregnancy—another problem common in central Appalachia. Kentucky, along with West Virginia, has among the highest rates of teen birth in the country, concentrated in central Appalachian counties. “The day I walked through the [high school] graduation line, I already had a one-year-old,” she says.

A few years later, she heard about a family wellbeing charity called Able Families, based in Mingo County, from another young mother. For a while, she participated in its programs, such as playgroups organized for mothers of young children. Then she was asked to join as a home-visit worker. Spaulding is now the director of Able Families, and is completing her masters in social work.

In addition to coaching mothers on childcare, Able Families sponsors an after-school program. It used to be that they’d prepare a light snack—until they realized it was often the child’s last meal of the day, and raised money to provide hot meals. On the first day of the new meal program, Spaulding and her staff had planned to let the kids loose on the playground before the meal. But the kids weren’t interested. “The first thing they got off the bus, they were at the fence like, ‘Where’s our food?’” More than a third of central Appalachian children live in poverty, compared with 21.7% nationwide, according to ARC.

The even bigger worry is that addicts with needy children aren’t coming forward for help at all. “There’s children starving over the weekend. And we don’t know who they are,” says Sandra Justice (no relation to the West Virginia governor), who works with Spaulding at Able Families.

The problem could start even earlier, though. “You go to the suboxone and methadone clinics, and you’ll see pregnant women in line,” says Spaulding. The local hospital—where around two drug-dependent babies are born every hour—now has a separate nursery tailored to help infants to undergo the excruciating month-long withdrawal. The infants are treated with methadone, which relieves opioid-addiction symptoms but is itself a powerfully addictive narcotic.

It’s not just material needs that local kids are missing out on. When the children put on performances, Able Families pulls out the stops to help parents and grandparents come to watch. It’s hard to get anyone to come, though. Spaulding recalls an episode when, just as the children were about to take to the stage to begin a play they were putting on, she and her staff spied out the window one of the little boy’s mothers driving up. The boy was excited, and the staff stalled while they waited for her.

But after a few moments, Spaulding saw the mother pull out again and drive off. She hadn’t been parking to see the performance, but lining up at the drive-through pharmacy that abuts the Able Families lot. Getting painkillers, Spaulding suspects.

Graduation events are similarly crushing. At a recent junior high ceremony, besides them, only one mother and one grandmother showed up. “Can you imagine your life if no one ever does that for you?” says Spaulding.

Spaulding’s own daughter was one of only a few kids in her high school graduating class of 106 to leave the area. She graduated from Alice Lloyd College in Kentucky last year and now lives in Nashville, working as a paralegal. (She told her mother she would go anywhere that had at least one stoplight.) Her middle child has wanted to be a chef since early elementary school. She had to explain to him that, with no real restaurants in the area, he would have to leave too. This fall, he started in the culinary program at Fairmont State, West Virginia. “I don’t think there’s anything wrong if they wanted to live here,” she says, “but I want them to know there’s opportunity in other places.”

Most kids in Kermit don’t get to glimpse those kinds of opportunities. Driving the ancient white Able Families van along Route 52, Spaulding recounts a recent field trip to Cleveland she took with her students. For nearly all of them, the trip to Hard Rock Café was the first time they’d been to a sit-down restaurant. In fact, many had never before left Kermit.

Spaulding was worried that the kids would be bored and disruptive when they toured Case Western Reserve University. However, the campus proved dazzling and exotic—especially their visit to a dorm. “So I could live here?” one girl asked.

“I was thinking, well, probably not—this place is really expensive,” Spaulding says. “But I told her, ‘Yes, you could go to school here and this could be your room.’ And they were all like, ‘To live in?’” she says. “They come from where even a community college is mostly unheard of. Especially thinking you could move away to a university—that’s not even in the realm of possibility.”

In this kind of environment, it’s perhaps unsurprising that residents of central Appalachia report feeling mentally unhealthy 25% more frequently than the average American. Nearly 20% of the area’s Medicare beneficiaries suffer from depression, compared with just over 15% nationwide. In May, a metastudy found that social isolation upped a person’s risk of dying by 29%.

Perhaps it’s not simply the unhealthy habits and pollution endemic to central Appalachia that are sickening residents and killing them prematurely. Rather, the wear and tear on the body from prolonged social and economic stress could be making people far more vulnerable to their harmful effects.

The problem we’re solving for

Nada White’s son, Dustin, is now 34. He says that growing up in the 1990s, the most exciting event of the year was the Coal Festival of Boone County. The multi-day coal-themed carnival featured music acts, fireworks and tilt-a-whirls—a much bigger affair than the county fair.

Dustin’s great- great-grandfathers would have looked forward to something very different. Back then, the biggest festival of the year in central Appalachia was election day—a state fair, market day, and political convention rolled into one, as Altina Waller, a University of Connecticut historian, recounts in Feud: Hatfields, McCoys and Social Change in Appalachia, 1860-1900. That disappeared in the coal camp era, as coal operators controlled political machines and, often enough, the votes of their employees. Nowadays, West Virginia frequently has the lowest voter turnout in the US: In 2008 and 2012, rates undershot the average by 11 percentage points.

Last year, however, that gap actually narrowed a little—shrinking to nine percentage points—thanks to enthusiasm for Trump. The central Appalachian coalfields were one of his biggest strongholds of support.

It’s not hard to guess why. Trump promised to revive central Appalachia’s coal jobs, a feat that would defy market trends. Central Appalachia’s remaining seams are harder to get at, making the coal generated uncompetitive with that mined elsewhere in the US. Environmental regulations have lessened demand from coal plants, though the far bigger factor is the abundance of natural gas, which has undercut coal prices.

As a result, the region’s coal industry is in the worst shape it’s ever been. In the last few years, companies have been winding down operations—some by choice, and many by way of bankruptcy. But coal is still the best-paying job around, and in many towns, the only one. Bringing those jobs back, it’s true, would save thousands of families and whole communities.

It turns out, Trump’s campaign promises weren’t just talk. In August, the Trump administration halted a comprehensive study, launched by the National Academy of Sciences in early 2017, to assess the health effects of mountaintop removal, citing cost concerns. Meanwhile, Trump appointed as head of the federal Mine Safety and Health Administration a former CEO of a coal company with a record of repeated safety violations, including at a mine where a preventable accident killed a miner in 2011. His energy department is investigating ways to force utility companies to subsidize coal company profits, reported Slate in Oct. 2017.

Whether or not this will be enough to postpone the long overdue creative destruction of central Appalachia’s coal industry remains to be seen. But for all the fanfare it’s received, Trump’s appeal to central Appalachians is neither original nor populist. It follows the same values and reasoning championed by a century of Appalachian politicians.

Trump, like generations of Appalachian politicians, says that he’s trying to save coal for the sake of the people. But the problem that he’s solving for isn’t how to invest in making people healthier and better educated. Nor is it how to make their children’s lives better or to expand their families’ opportunities.

Rather, the problem Trump is intent on solving is how best to give vast, distant corporations more opportunities. To revive an old oligopoly, instead of innovating new work. To subsidize producing more coal, instead of spending on making the region’s people more valuable. To stake the region’s future on a finite resource, at the expense of the ultimate renewable one—human potential.

This isn’t just a Trump thing. At a national level, US politicians, corporate chieftains and other civic leaders continue to ignore the flaws riddling their own growth model. Like the coal-backed politicians counting on boom to follow bust, the nation’s leaders continue to expect the business cycle to buoy growth, failing to grasp how years of increasing inequality in wealth, income, opportunity, and health have cannibalized the very demand needed to sustain it. While they dither on investing in infrastructure, technology, education and health care, the country’s reliance on welfare continues to climb as labor force participation slides. Taxpayers are subsidizing companies to underpay retail workers, just as they’re paying for coal companies to lop off mountaintops.

And though central Appalachia’s health and economic problems are unusually pronounced, the phenomenon certainly isn’t anomalous. According to a recent county-by-county analysis by the Economic Innovation Group, a entrepreneur advocacy and policy group, the number of jobs and new businesses in distressed communities in the US—central Appalachia among them—haven’t grown at all since 2000. Half have suffered net losses of both.

Meanwhile, two years ago, national life expectancy in the US fell for the first time in decades. It dropped again last year. It could be an anomaly—two years hardly makes a trend. But it could also mark a shift in its people’s fortunes that is all but unthinkable in a country that has grown to be the world’s richest and most powerful.

It’s a blow that hit many central Appalachian counties a decade ago, the grim conclusion of the great cynical experiment played out upon its people. Americans, like central Appalachians, are told that problems of health and poverty stem from the moral failings of individuals, not of society. Meanwhile, their country’s institutions are embracing the same ideology that laid waste to the coalfields—that profit equals prosperity, regardless of its true costs.