The key to peace and self-acceptance lies in understanding 3.5 billion years of life on Earth

Have you ever longed to shine like a star and be part of something great—a major artistic work, say, or a scientific discovery?

Have you ever longed to shine like a star and be part of something great—a major artistic work, say, or a scientific discovery?

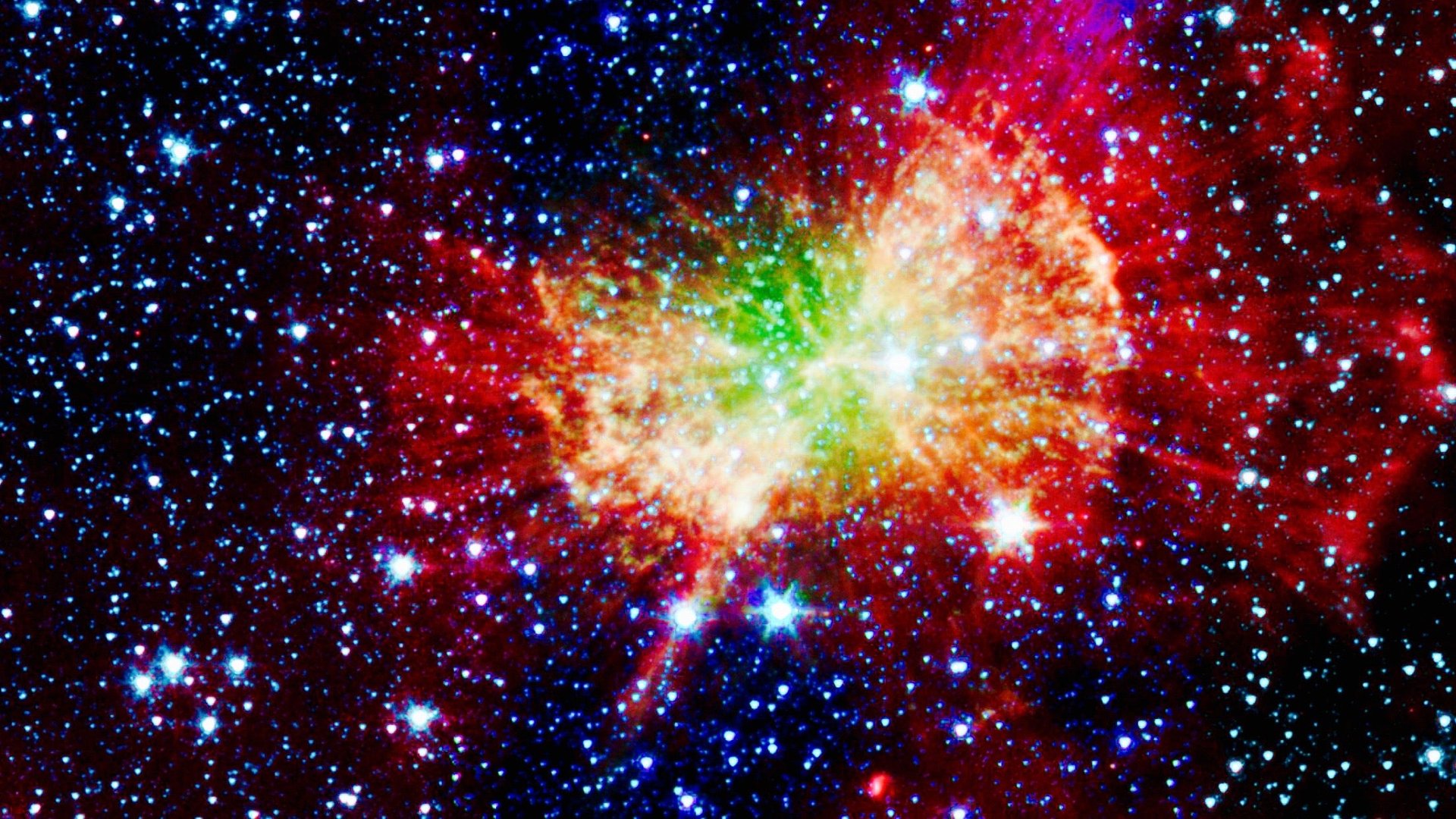

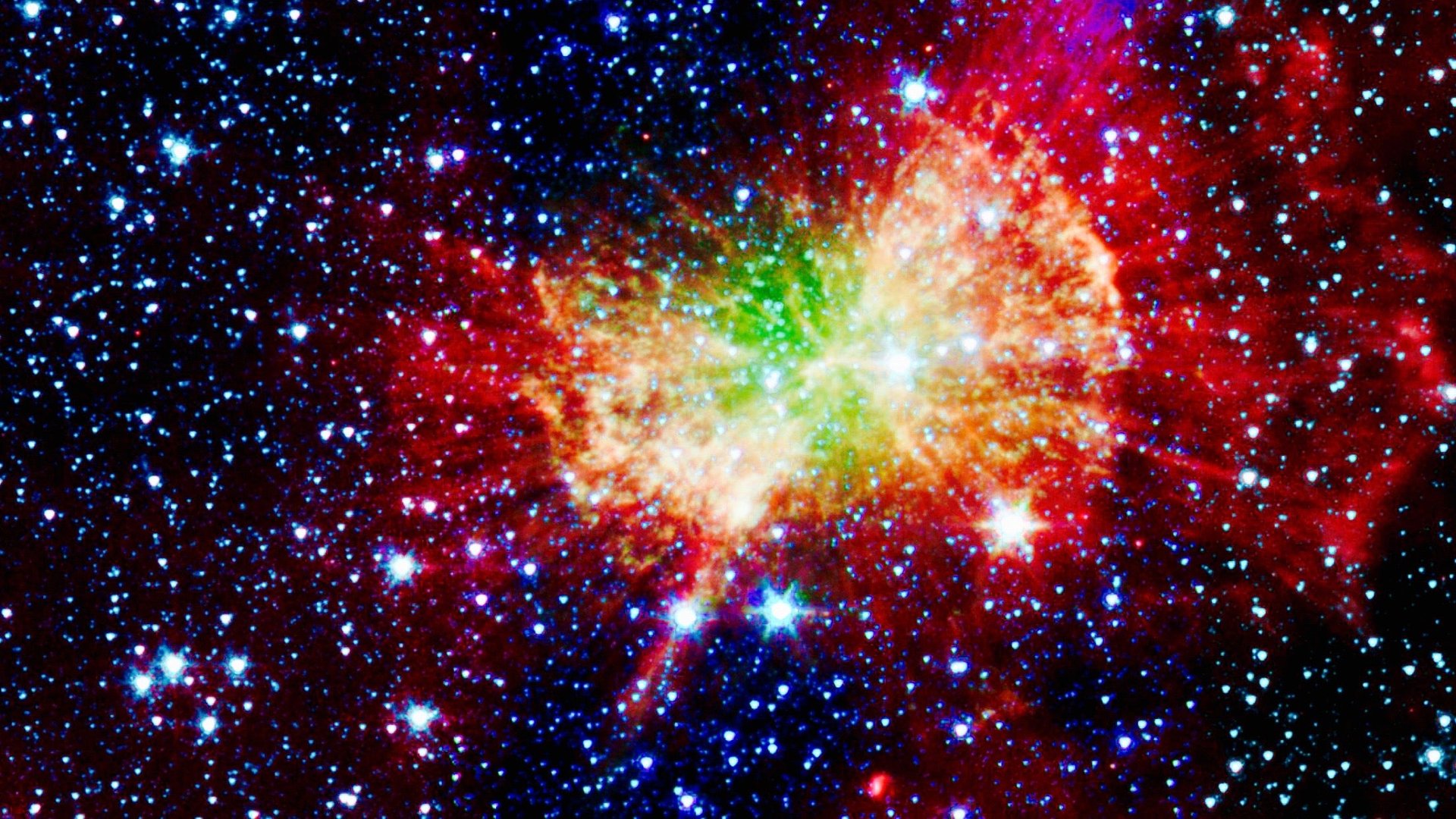

Dream no more. It’s already happening. In the big picture of the universe, we’re all quite literally the stuff of stars—each of us equal inheritors of a shared home and history, according to architect and social and environmental activist Carl Anthony, author of The Earth, the City, and the Hidden Narrative of Race.

Anthony’s book argues that the tale of our cosmic history has the power to change the way we think and live. Life has existed on Earth for at least 3.5 billion years; humans, by contrast, have only been around 300,000 years. That’s barely the blink of an eye in deep time. We’re bit players in the epic work known as the cosmos.

Understanding this can completely shift your personal perspective, Anthony writes, and help save the planet from destruction due to human negligence. In fact, contemplating this long story, and the brief role that humans play within it, liberated Anthony from a psychological prison he once thought was inescapable.

Space and race

Anthony is African-American. He grew up poor in a mostly black neighborhood in Philadelphia in the 1940s, and participated in the civil rights movement in the late 1950s and 1960s.

Despite being sent to vocational school as kid and leaving home young, he made his way to Columbia University in New York in 1960. There were few black architecture students at the university, and no professors to serve as suitable mentors. All discussion of culture was limited to Western traditions. Anthony couldn’t relate to his fellow students, or figure out how his professors’ lectures on the grandeur of Greek and Roman architecture were connected with the impoverished neighborhoods in nearby Harlem.

Nonetheless, he completed his studies and, with money from a school grant, set off in search of his history, traveling through Africa to see its old and new constructions. He would go on to devote his life to considering different aspects of identity, particularly race and class, to understand the way that accidents of birth dictated the course of people’s lives—from the spaces in which they live to their opportunities, earnings, and aspirations.

He taught architecture at the University of California-Berkeley, worked as community advocate, founded the San Francisco Bay Area social and environmental policy and advocacy group, Urban Habitat, and starting the seminal publication Race, Poverty and the Environment Journal in 1990. Anthony did a lot.

Still, he struggled personally with a sense of loss. His ancestors were brought to the US from Africa during the slave trade, forced to participate in deforesting the land and ridding it of Native Americans. It was a history he had to claim, but that devastated him. Meanwhile, his work focused on the poverty that results from segregated cities, so he could see clearly that African-Americans were still struggling with slavery’s legacy. History felt heavy and dismal. The present was a struggle. And a bright future was difficult to imagine.

Scientific mystic

In 1992, Anthony’s ideas about identity were totally transformed while reading the book The Great Work, by Catholic priest and cultural and religious scholar Thomas Berry.

Berry embraced evidence of evolution, while discussing cosmic history in mystical terms. He called the universe “a great long celebratory dance.” Berry noted, too, that in the cosmic view, humans are merely “creatures within the community of life-systems,” not conquerors. He argued that we needed to rethink our approach to the environment and Earth’s other inhabitants, as well as to each other.

The great work of the time, according to Berry, was to write and adopt a new narrative in which all humans identify primarily as a single species among the many types of life, rather than dividing ourselves along racial, religious, and national lines. And Anthony, who had spent so much of his life exploring intersections of identity, was immediately convinced.

Outside the box

“The story of the Big Bang and the formation of galaxies, stars, the solar system, and eventually us offers deeper meaning to our lives,” Anthony writes. Berry’s articulation of cosmic history gave the architect a new sense of wonder about existence. He writes that, for the first time, he experienced himself “as stardust come to living form in an amazing self-organizing universe.”

With an understanding of the really big picture, Anthony’s view of his own history shifted. He explains:

This [deep time] perspective inspired me to break out of the claustrophobic identity box in which the culture of white America confined me … [Contemplating deep time] has enabled me to free myself from the shame and horror of my ancestors being caught in the most traumatic events in human history: the trans-Atlantic slave trade … My history goes back to the Big Bang, or as Berry called it ‘the primordial Flaring Forth.’

This new perspective transformed Anthony’s sense of psychological isolation into a deep identification with his fellow humans, a sense that the differences which seem so great in his life are small on a grand scale.

That doesn’t mean that Anthony discounts the real problems of racism and poverty, which plagued his own life and the lives of so many others. In his book, Anthony explicitly lays out his support for the Black Lives Matter movement, for example, noting that in order to appreciate life, one must first be able to survive it.

Instead, Anthony says that an expanded view of the universe can help us recognize that we all have an equal stake in the world. And so he rejects arguments that environmentalism is the purview of the privileged, barely a concern for the poor or powerless. Quite the contrary, environmental injustices disproportionately influence underprivileged communities, so those groups have the greatest stake in claiming their space on the planet and ensuring humanity understands our role here, according to Anthony.

Applied science

Most of us barely have a handle on today, much less recent history. Rarely, if ever, do we contemplate the universe’s beginnings and our place in it—there’s too much to tweet!

Instead, we accept dominant narratives that divide people into tribes, colors, ideology, and geography. We behave as if the planet was created for humankind, as if little people, with our tiny differences, are the point of all creation. With this narratives come damaging psychological baggage that isolates us from one another and from our responsibilities to a shared planet.

At 78, Anthony has little patience for those old yarns. He believes humanity urgently needs a redraft, so that we can together find meaning in a grand scientific narrative that promotes environmental consciousness and liberates all to be the stars we really are. Anthony invites everyone to collaborate on writing our story. “We belong in the universe,” he writes. “We are an expression of the unlimited creativity that lay hidden in its depths before time and space. That creativity is in each of us. Nobody can tell us how to see ourselves or what we can and cannot accomplish. So I ask you … How will you contribute to this great adventure?”