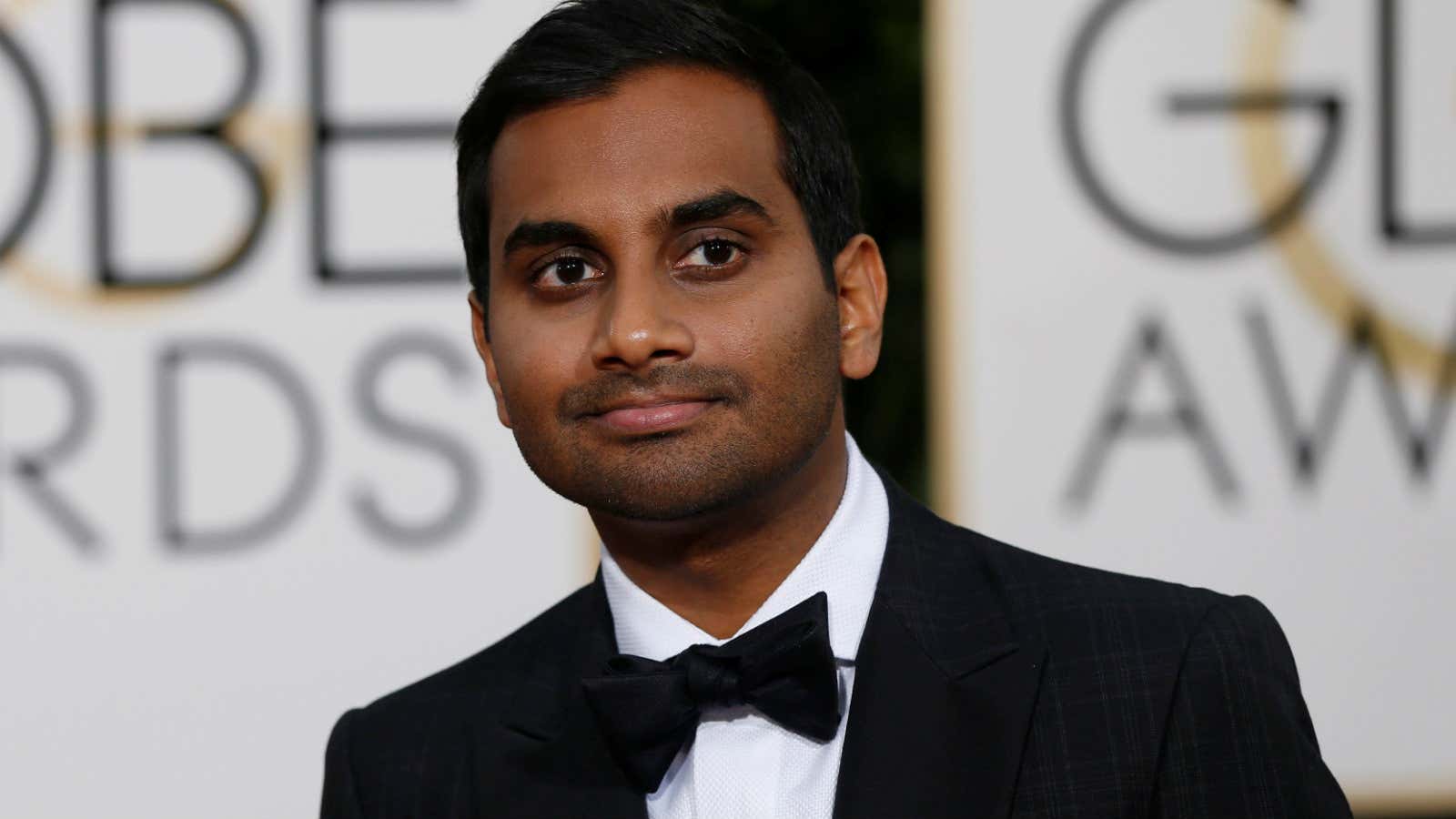

It’s easy to support Aziz Ansari and his work. He’s a poster boy for representation done respectfully and, well, marks the first time someone contextualised the desi south Asian identity instead of merely exploiting it. He also represents a certain educated ability of the international, pop-culture-consuming class of young Indians who have been trying to, quite desperately, find a voice they can call their own. He’s like us, because he’s one of us. Which is why allegations of sexual misconduct against Ansari hit a very raw, uncomfortable nerve for many of his Indian audience.

Ansari’s outspoken, insightful championing of feminism was almost too good to be true. To see a brown man in a position of substantial social power taking his space and ceding it to causes that are very intrinsically in antithesis to what his background has represented was not just refreshing—it was a moment of cultural reckoning. His work forced a lot of Indians to pause and reflect on their own realities and how they navigated an increasingly fraught world that forces a political underlining on all that is personal. In particular, Ansari became a template for the “woke brown man”—someone who recognised the layers to his own privilege and tried to work his way through it. His snappy, witty descriptions that cut through intersectionality became conversation cue cards for people who needed a direction to push their budding ideological leanings towards. And then came Modern Romance.

To watch a man speak of respect, consent, and enthusiasm in dating is rare—and special. To watch a brown man do the same is a revelation. Most Indians understand dating, as a construct, from the American sitcoms we consumed as ’90s kids, and the stalker-ish, borderline harassment Bollywood movies told us was “love.” Suddenly, here was a line of thought most of us could actually see reflected in our own social milieus. When Ansari speaks of the trials and travails of online dating, texting rules, and romantic vagaries, he speaks in a language we understand. His character in Master of None echoed this. He is definitely Indian, and definitely not reduced to his Indian-ness. He spearheaded a shift towards a certain cosmopolitan desi identity that isn’t a stereotype, but a complex, layered approach to the world. He made it cool to break out of the stratified desi moulds. It was suddenly okay to be vulnerable and struggle with ideas instead of always having an answer.

None of this excuses what the anonymous account of Grace alleges he did. But the Babe piece was an average piece of journalism. It was sensationalised, unnecessarily soppy, and manufactured for virality. The language of it was meant to polarise, and it did. The mere fact that Babe approached Grace for her account instead of the other way around forces a harsh scrutiny that the piece may not be able to withstand with its credibility intact.

Having said that, Grace’s story isn’t new. That’s possibly why the piece struck such an angry nerve. Ansari’s quick, quiet apology sounded more like the words people wanted him to say than the product of actual introspection. Here, it would be easy to forgive him—the desi woke bro—but it’s important to remember that representation doesn’t excuse sexual aggression, and nor does performative activism. For a man who literally wrote a book on the social cues men and women engage with in romantic relationships, he was, as any reading of the piece will tell you, awfully obtuse and callous. The piece, and the hot takes it has spawned, represent a very crucial juncture in the larger, overarching conversation about the politics of sexuality we’ve been skirting around for the past few years. The Weinstein moment blew up, and so did #MeToo, with women coming forward with terrifying, heartbreaking stories of sexual trauma over the years—but is the tangent they’re on enough?

To dismiss the allegations as someone seeking revenge for a date gone bad reduces the scope of what can, and must, be spoken about. When the conversation centres around assault instead of encompassing what leads to it, we lose crucial insights into what can change on a more organic, fundamental level. What Ansari did doesn’t quite count as assault in the legal sense—but it begs the question of why legality is the only benchmark we keep for ourselves. To reduce the dehumanisation and discomfort of a woman to “bad foreplay” is to excuse the willful, clumsy disregard for a woman as a person. When people say that consent relented (versus consent given enthusiastically) is still consent, aren’t we doing a disservice to the very idea of consent as it stands today?

Grace’s account rendered her as someone in a clearly socially disadvantaged position, whose consent was, at best, assumed, and at worst, wrested away from her till she gave in. That’s not consent. To claim that her entering his house was explicit consent draws away from the fact that sex is not a singular activity. She was comfortable with one level of intimacy, and not with the rest—and that’s okay. She had the right to say no at any point of the physical interaction, and it was his duty, as the clearly privileged party, to ask her if she was okay with going ahead. He didn’t, and that automatically tilts the favour away from him.

The betrayal of Aziz Ansari will soon be forgotten, but the questions it has raised will not. This is a confirmation of some of the most rankling fears women everywhere wrestle with—if a man says he’s a feminist ally, can I trust him? Should I? It’s exhausting living in a world where everything is conspiring against you, and women have been pushed back into the same corner again and again. This also forces us to step back and question where #MeToo goes next. Do we scale? Do we consolidate? Do we simply struggle to survive?

There are no simple answers. There shouldn’t be any, either. It’s time to move beyond catchphrases and linearity, and wrangle with tougher, murkier realities beyond hashtags and trends. It’s not going to be easy to let go of heroes we create out of people who express basic human decency—and maybe that’s exactly what we need to do. Pull our heroes off their pedestals and demand better of them.

This post was corrected: Aziz Ansari’s book is titled Modern Romance, not Modern Love.

We welcome your comments at ideas.india@qz.com.