In 1572, the killings began. That year, authorities in the tiny settlement of St Maximin, in present-day Germany, charged a woman named Eva with using witchcraft to murder a child. Eva confessed under torture; she, along with two women she implicated, were burned at the stake.

The pace of prosecution picked up from there. By the mid-1590s, the territory had burned 500 people as witches—an astonishing feat, for a place that only had 2,200 residents to begin with.

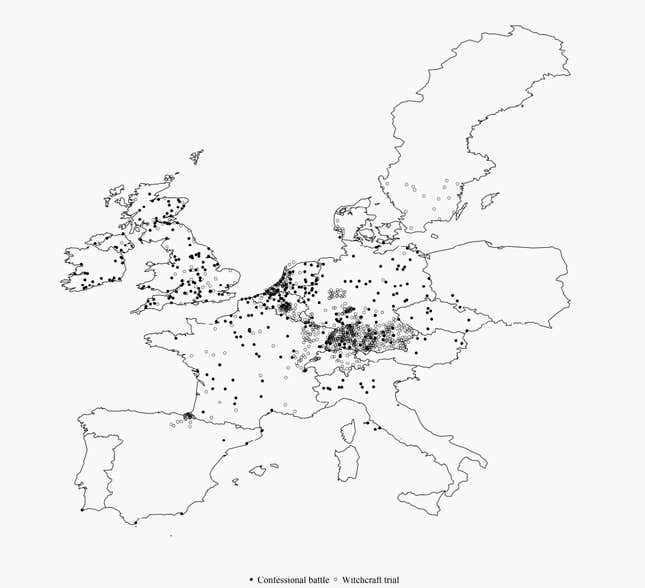

Why is it that early modern Europe had such a fervor for witch hunting? Between 1400 to 1782, when Switzerland tried and executed Europe’s last supposed witch, between 40,000 and 60,000 people were put to death for witchcraft, according to historical consensus. The epicenter of the witch hunts was Europe’s German-speaking heartland, an area that makes up Germany, Switzerland, and northeastern France.

Conventional wisdom has chalked the killings up to a case of bad weather. Across Europe, weather suddenly got wetter and colder—a phenomenon known as the Little Ice Age that pelted villages with freak frosts, floods, hailstorms, and plagues of mice and caterpillars. Witch hunts tended to correspond with ecological disasters and crop failures, along with the accompanying problems of famine, inflation, and disease. When the going got tough, witches made for a convenient scapegoat.

But a recent economic study (pdf), which will soon be published in the The Economic Journal of the Royal Economic Society, proposes a different explanation for the witch hunts—one that can help us understand the way fears spread, and take hold, today.

The economic hypothesis

This alternative theory comes down to market competition—between churches. In early modern Europe, Protestantism emerged as the first truly viable challenger to the Catholic church’s hold on the population. The study views the Catholic and Protestant churches as competing firms, each in the business of supplying a valuable service: Salvation.

As competition for religious market share heated up, churches expanded beyond the standard spiritual services and began focusing on salvation from devilry here on earth. Among both Catholics and Protestants, witch-hunting became a prime service for attracting and appeasing the masses by demonstrating their Satan-fighting prowess.

“Similar to how contemporary Republican and Democrat candidates focus campaign activity in political battlegrounds during elections to attract the loyalty of undecided voters, historical Catholic and Protestant officials focused witch-trial activity in confessional battlegrounds during the Reformation and Counter-Reformation to attract the loyalty of undecided Christians,” write the study’s authors, Peter T. Leeson, an economist at George Mason University, and Jacob W. Russ, an economist at Bloom Intelligence, a big-data analysis firm. When it comes to winning people to your side, after all, there’s no better method than stoking fears about an outside threat—and then assuring them that you, and you alone, offer the best protection.

This concept goes a long way toward explaining not just why witch-hunting mania exploded in Europe, but also why it took hold where it did. Namely, in Germany.

“Neither holy, nor Roman, nor an empire”

Until the 1500s, the Catholic Church had claimed a monopoly on religion. Secure in its dominance, the Church employed a basic competitive strategy against the occasional challenger: it labeled proponents of other religions “heretics” and either forced their conversion or simply killed them. The Church’s two main tactics in this coercive strategy were inquisitions and crusades.

With the German monk Martin Luther, however, that strategy stopped working.

By nailing his Ninety-five Theses to the door of his local Catholic Church in 1517, Luther was acting as an early consumer protection bureau of sorts, blasting the Catholic church for exploitative practices. The promise of superior religious service sparked the Protestant Reformation, with Swiss theologians Ulrich Zwingli and John Calvin piling on, adding to the movement’s momentum.

Per usual, the Pope declared Luther a heretic and banned the Ninety-five Theses. It turned out, though, that the Catholic Church’s coercive strategy—which worked well in Spain, Portugal, the Italian city-states and other places where its power was centralized—broke down at the borders of Luther’s homeland, the Holy Roman Empire.

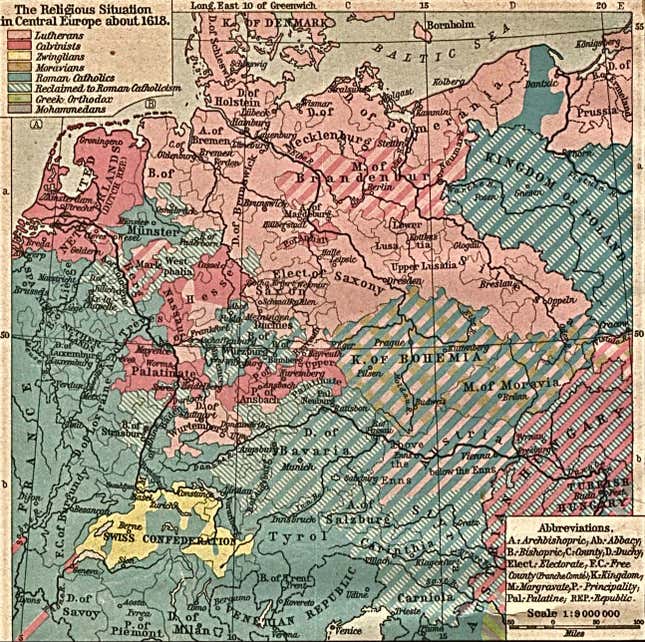

For many, the most memorable tidbit of antiquity about this messy dynasty is that, as Voltaire famously remarked, it was “neither holy, nor Roman, nor an empire.” Indeed, it had no centralized religion, was mostly German, and operated as a psychedelically complex patchwork of districts that, as the Middle Ages wore on, wrested increasing sovereignty from the Emperor.

This decentralized structure made enforcing Catholicism and rooting out Protestantism much trickier. Plus, Luther had a hometown advantage. Before long, a slew of German princes had flipped over to Lutheranism—enough that, by 1555, they were powerful enough to force the Emperor to decriminalize Lutheranism. The name of this agreement, the Peace of Augsburg, belies its result. With Lutheranism now officially given the green light, violence broke out across the Holy Roman Empire, as princes fought to force their faith on neighboring territories.

Battleground Germany

As a result, Germany became the bloodiest battleground in the Catholic-Protestant contest. Between 1300 and 1850, it was home to 104 religious battles—a quarter of the European total, according to Leeson and Russ’ dataset, which covers 21 European countries.

Invasion wasn’t necessarily the most effective way of winning converts. With Catholic-Protestant rivalries now out in the open, officials had to boost the appeal of their brand to religious consumers by providing more services. Protestants, for instance, offered lower prices for tithing, while Catholics reaffirmed the cult of saints, which encouraged grassroots engagement by beatifying and canonizing candidates venerated by local communities. (Among those selected post-Reformation were Albertus Magnus, the great German philosopher and patron saint of medical technicians, and Saint Charles Borromeo, a rabid witch-hunter who also happens to fend off ulcers.)

But in these unstable times of brutal weather and constant warfare, the hottest service to provide was protection against Satan and his minions: witches.

For centuries, common folk had widely believed in witchcraft. People bought and sold magical services like love potions and spells to help find stolen belongings. Up until around this time, the Catholic Church hadn’t been that worried about witches and witchcraft, let alone interested in prosecuting them.

That stance reversed by the mid-1500s, as Lutheranism gained ground. Protestants tended to be much warier of witchery; Luther himself authorized the execution of four accused witches, while Calvin urged Genevan officials to wipe out “the race of witches,” notes Gary Waite, a history professor at the University of New Brunswick, in The Oxford Handbook of Witchcraft in Early Modern Europe and Colonial America. Catholic leaders were getting nervous. They responded with some of the most brutal massacres, St Maximin’s among them. That, in turn, inspired Lutheran authorities to up their witch-hunting game still more.

Witch investigations were time-consuming and expensive. But the payoff could be worth it. After all, what clearer way was there to quantify the fight against Satan than a big bonfire bodycount?

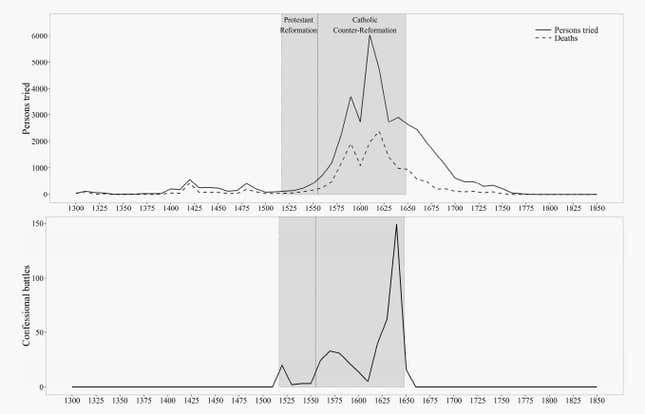

The research by Leeson and Russ shows that religious competition did, indeed, spark witch hunts. In addition to collecting data on religious battles, they amassed a dataset of more than 43,000 witchcraft prosecutions in nearly 11,000 separate trials. Sure enough, in places and periods where confessional competition was fierce, witch hunts intensified. More than two-thirds of the witch trials and 90% of the religious battles occurred during the Counter-Reformation, when Catholics stepped up their response to legalized Lutheranism between 1550 and 1650.

Witch trials were also greater and more frequent in Germany and Switzerland, where religious contests were most heated. More than 40% of Europeans executed for witchcraft were in Germany, according to the new dataset. Tellingly, the slaughter subsides after 1648, when the Peace of Westphalia brought an end to religious wars by establishing the geography of Catholic and Protestant monopolies and mandating tolerance of mainstream sects of Christians, regardless of official religion. That drop-off occurred well before the last gelid gasp of the Little Ice Age swept the area in the late 1600s.

Meanwhile, in Catholic strongholds—where Inquisitors were busily persecuting “heretics”—witches were mostly ignored. The infamously savage Spanish Inquisition executed no more than two dozen alleged witches; Portugal put to death around seven.

The analysis explains why witch hunts took off in certain geographical areas and never really took hold in others. But why were Germans and their neighboring regions so much more spooked about witches than other Europeans in the first place?

How the modern witch was made

Before the 1400s, Europeans generally believed in magic. But what that looked like varied dramatically by place, as Ronald Hutton, a history professor at the University of Bristol, argues in The Witch: A History of Fear, From Ancient Times to the Present. Sicilians told of gaggles of alluring women with the hands and feet of animals, while Norwegians shared their world with earth trolls. There was no pan-European agreement on who witches were and what exactly they did, assuming they even believed in witches at all. (Many cultures lacked this concept entirely.)

There were a scattering of witch trials in the early Middle Ages—many of them mob violence—but the accused confessed to notions derived from their local folklore, says Hutton. Witches of this era weren’t perceived as satanic, and they seldom gathered in groups.

Then, all across Europe, accused witches began recounting strikingly similar activities. They murdered children and rode wooden implements smeared with a flight-enabling ointment made of the fat of a murdered baby. They traveled by night to secret witch confabs in which they communed with the Devil, gatherings of a vast, coordinated Satanic sect. This concept of witches continued throughout the “Great Hunt” era of European witch trials, and persists in a much friendlier image we have of witches riding broomsticks to coven meet-ups today.

So where did this witch stereotype come from? Scholars point to the traveling friars in the Valais area of the Swiss Alps in the 1420s, who had been dispatched to combat heresy. As they traveled from town to town in this mountainous region at the intersection of Germany, France, and Switzerland, these preaching friars absorbed and transmitted popular fears. Eventually, they brought word back to religious and secular officials who documented these stories.

A slew of theologians began publishing demonology handbooks and guides to exterminating witches, firming up notions of what the witchy do. For instance, that horrible baby-fat spell is straight out of Malleus Maleficarum (The Hammer of Witches). Written by a German Catholic inquisitor in 1487, Malleus Maleficarum was the most famous treatise on rooting out sorcery—basically the Dummies Guide to Witch-killing. For nearly two centuries after its publishing, it sold more than any book except the Bible. By the 1500s, local pastors had joined preaching friars in spreading this newly standardized concept of witches across the mountainous German-speaking region, priming paranoia that the Catholic-Protestant holy wars soon transformed into full-blown hysteria.

It’s easy to dismiss this terrifying historical episode as irrational pitchfork-wielding by medieval mobs. For the most part, though, it wasn’t. Consider the careful cost-benefit analysis made in Schongau, a village in southern Germany. So desperate were the impoverished townsfolk to rid their town of devil-driven catastrophe, they offered to sell their communal forest to pay for the services of a renowned witch executioner, as eminent witch historian Wolfgang Berhringer recounts. Villagers trusted their institutions and the information they spread. Unfortunately for the tens of thousands tortured and burned, faith can easily mutate into fact.