The 17th century Dutch painter Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn is remembered as one of the most prolific artists of his time. He is known for his paintings of the countryside and biblical scenes, now displayed in museums around the world. But his lesser-known titles feature some unlikely subjects: Mughal emperors Jahangir, Shah Jahan, and Aurangzeb from far away India.

Rembrandt was born in what was then called the Dutch Republic, and never visited India. But his 23 surviving drawings of Mughal emperors, princes, and courtiers, believed to have been produced between 1656 and 1661, show how trade between the East and West sparked an unlikely instance of creative cross-pollination.

One of these detailed drawings, which features Shah Jahan and his son Dara Shikoh, belongs to the collection of the J Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles. This museum will soon launch an exhibition titled Rembrandt and the Inspiration of India that reveals how the iconic European painter was inspired by artists from thousands of miles away. It will include 22 of his works, alongside Mughal paintings with similar compositions.

Rembrandt’s paintings are believed to be based on Mughal works of art brought to Amsterdam by the Dutch East India Company, which began trading in India in 1604. Over the following years, the Dutch established factories and warehouses along the coast near the city now known as Surat, in Gujarat, and in Calcutta (Kolkata). As their business, exporting cotton, silk, and even opium, flourished, the Dutch also carried home many Indian artefacts, some of which would end up in Rembrandt’s personal collection.

As Stephanie Schrader, curator of the exhibition, notes in its catalogue, the Dutch painter owned “East Indian cups, boxes, baskets, and fans as well as 60 Indian hand weapons, including arrows, shafts, javelins, and bows, and a pair of costumes for an Indian man and woman.”

Rembrandt himself doesn’t seem to have owned the Mughal paintings he tried to imitate, Schrader says. However, he may have had access to those owned by his clientele, which included wealthy merchants who made their fortunes working for the Dutch East India Company. These merchants were likely to have come in contact with the trade representatives of the Mughals.

In his drawings, Rembrandt paid close attention to the way Indians dressed.

“Rembrandt’s copies reveal his fascination with the Mughal style as well as his curiousity about the depiction of elaborate clothing and jewelry,” Schrader writes in the catalogue. “The fine tasseled lappets of the Muslim jamas (stitched coats) at the right shoulder, the intricate folds of the turban, the rouched paijamas (loose pants), the transparent muslin skirts, the soft leather folds of the upturned jutis (shoes), and the intricately patterned patkas (sashes), all rendered by Rembrandt in laborious detail, are unmistakably Mughal.” She adds that the Dutch master even tried to depict their turban ornaments, decorated daggers, and sword hilts.

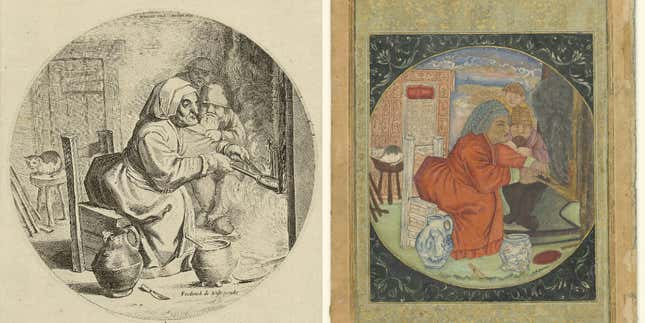

It also turns out that this cross-pollination worked both ways: The Mughal emperors were great patrons of the arts, and the empire’s artists, too, were known to paint western rulers and distinctly European scenes. For instance, included in the Getty exhibition is a painting by an unknown Indian of an aged Dutch woman making pancakes, a theme often found in the oeuvres of Rembrandt and other Dutch artists themselves. The Indian has woven in Mughal elements in his interpretation, including a coloured, cloudy sky and local architecture.

Here’s a selection of Rembrandt’s works, inspired by Mughal paintings: