In 1873, Japanese officials considered switching the national language to English

Japanese speakers use a lot of English words. There is baa, meaning “bar,” hoteru for “hotel,” and hundreds of others. Using English can give whatever a Japanese person is saying a touch of sutairu, or “style”—and doing so has been fashionable since well before the spread of internet and Hollywood movies.

Japanese speakers use a lot of English words. There is baa, meaning “bar,” hoteru for “hotel,” and hundreds of others. Using English can give whatever a Japanese person is saying a touch of sutairu, or “style”—and doing so has been fashionable since well before the spread of internet and Hollywood movies.

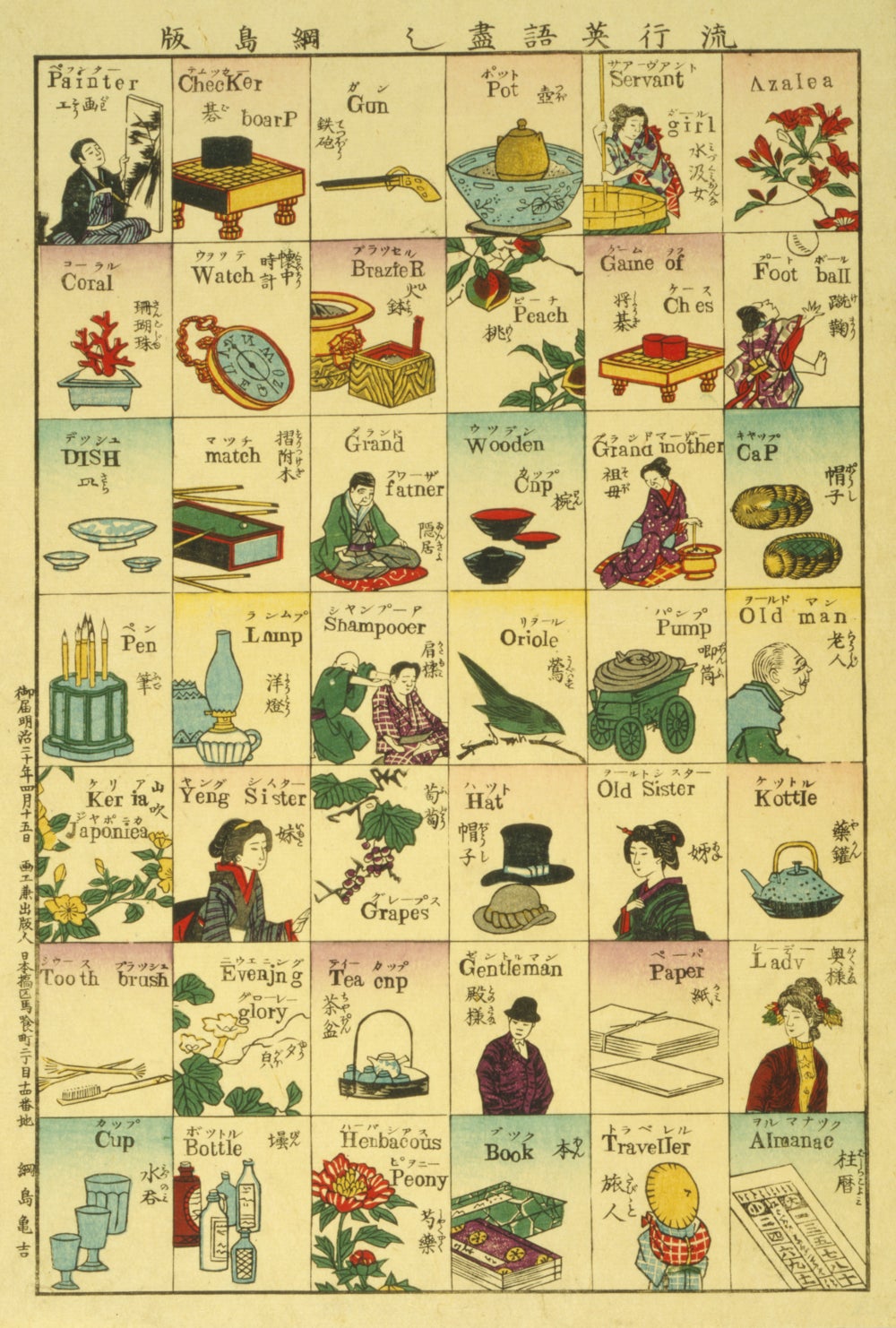

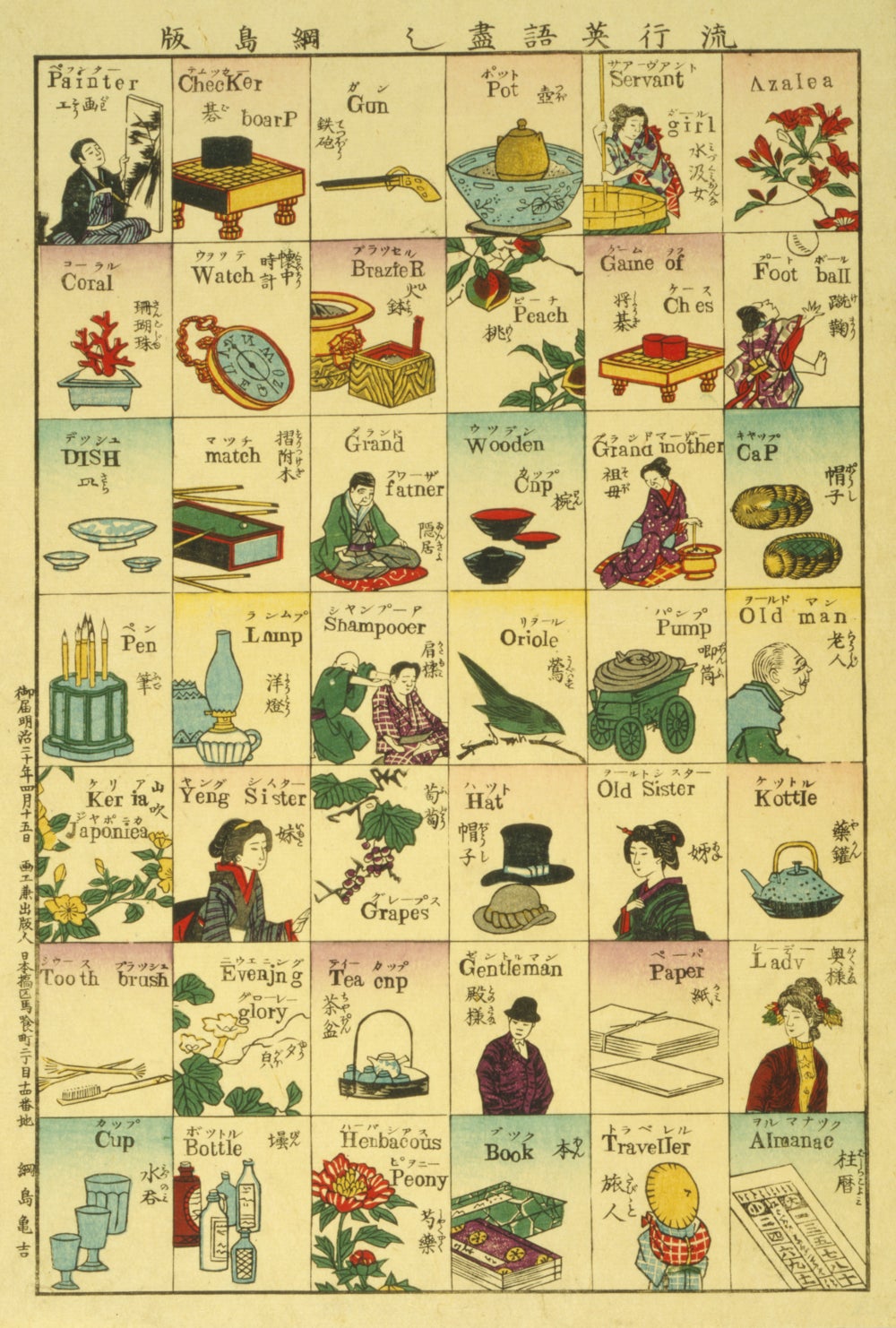

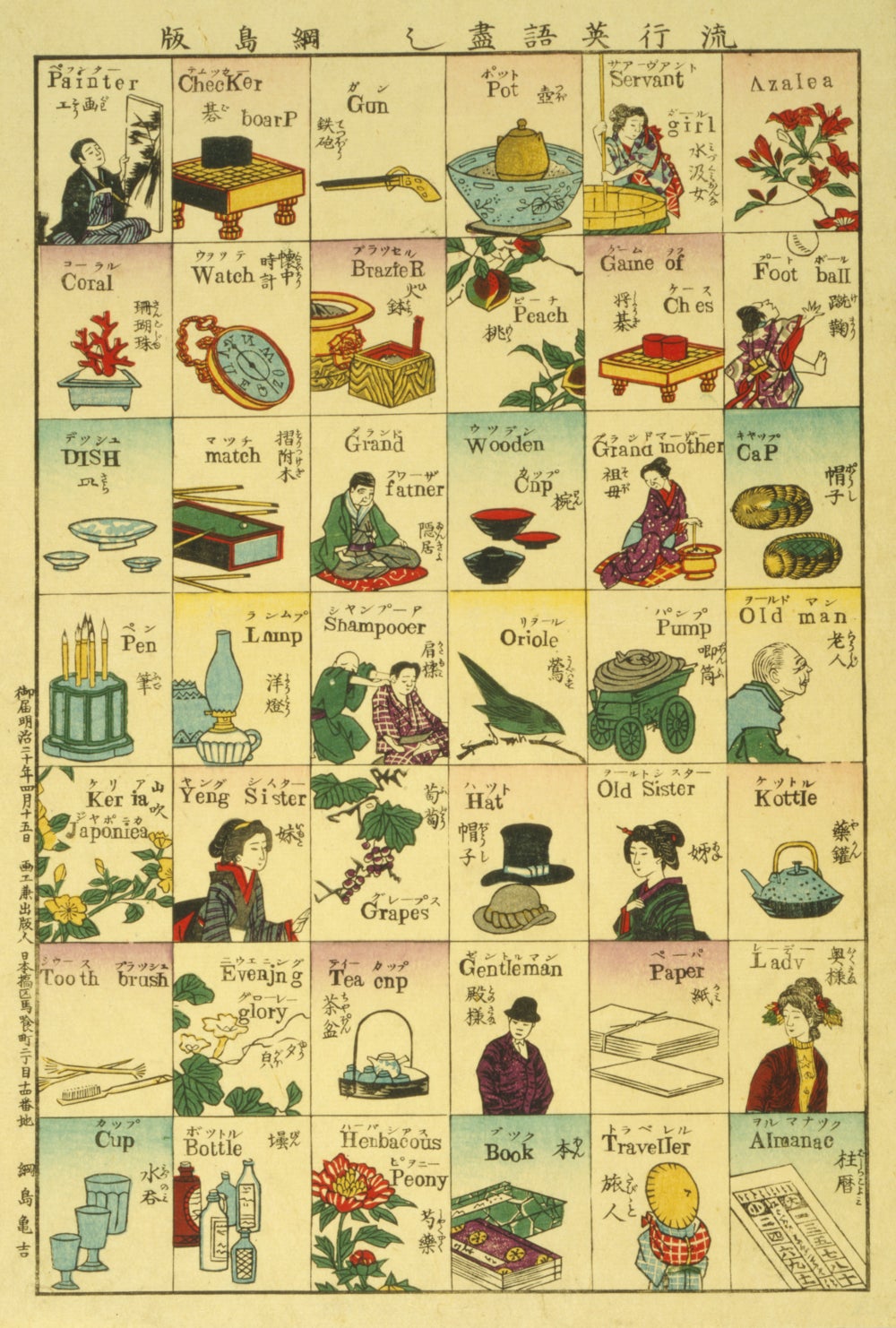

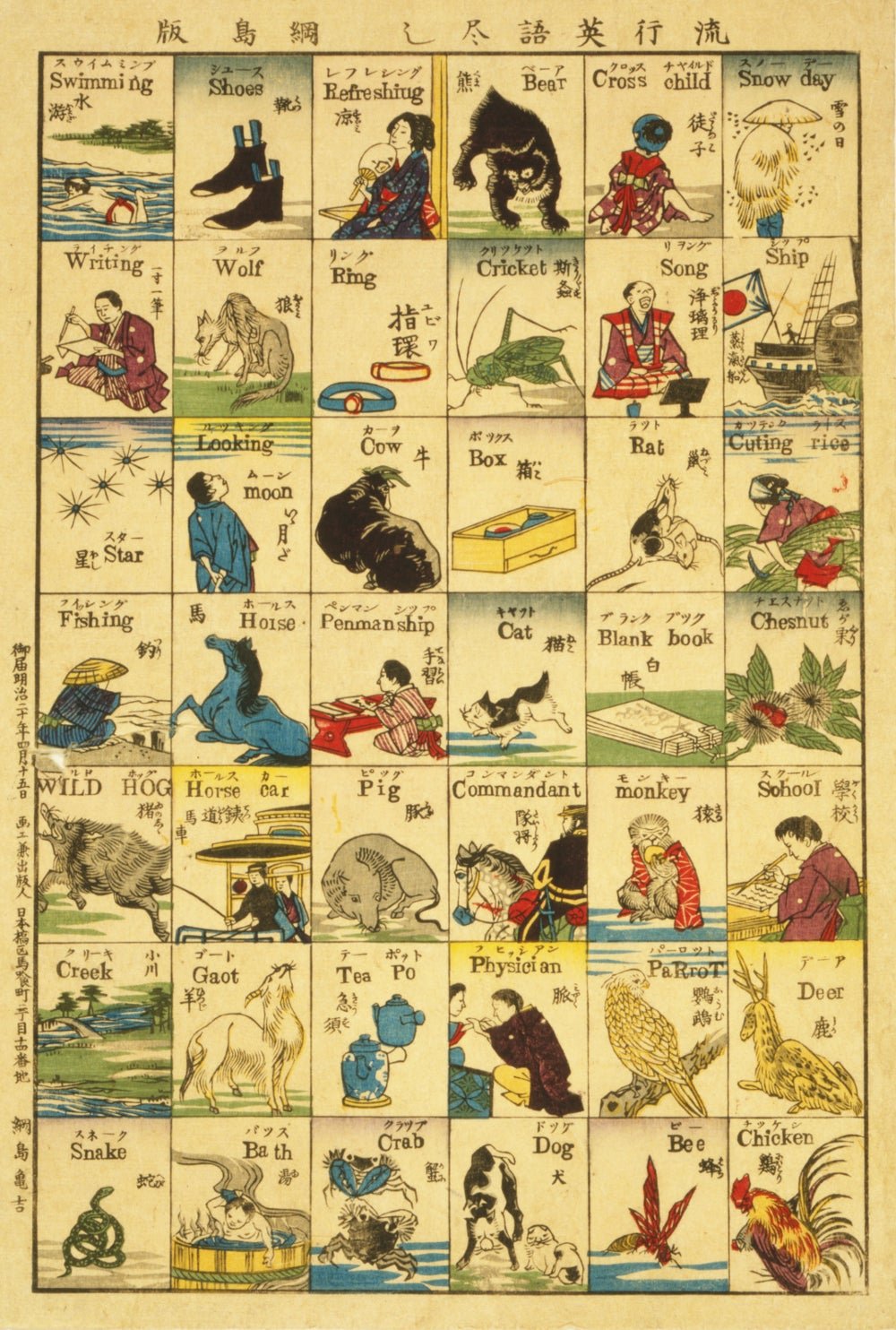

Back in 1887, the Japanese artist Kamekichi Tsunajima produced a series of woodcuts titled “Fashionable melange of English words.” Most of the words are not obviously “fashionable” to the contemporary reader. Monkey? School? Cat? Penmanship? There are also a number of errors, like “gaot” instead of “goat” and “refreshiug” instead of “refreshing.” The point, though, is not that these will teach anybody English. It’s that they reflect a growing interest in English in 19th-century Japan.

The woodcuts were produced not long after the US navy showed up in Japan in 1853 to force a trading relationship on the island, putting it on course to modernize in the mold of Western countries. This was the Meiji Restoration, an imperial rule that was determined to adopt any ideas or technologies from the West that would help Japan compete. And one such technology was the English language.

During the Meiji period, influential Japanese scholars argued that the country should ditch its millennia-old language in favor of English. It had already become the language of trade and science, and was seen to be the language of modernity. The biggest advocate of this radical idea was Mori Arinori, Japan’s first ambassador to the US and education minister during Meiji rule.

Mori made his case in the introduction to a book published in 1873:

The commercial power of the English-speaking race which now rules the world drives our people into some knowledge of their commercial ways and habits. The absolute necessity of mastering the English language is thus forced upon us. It is a requisite of the maintenance of our independence in the community of nations. Under the circumstances, our meagre [sic] language, which can never be of any use outside of our islands, is doomed to yield to the domination of the English tongue, especially when the power of steam and electricity shall have pervaded the land.

His suggestion never got enough support to turn Japan into a kind of early Singapore, where the government willed citizens into becoming fluent English speakers, even though it was not widely spoken at home. But it is part of the long-running influence of English on Japanese, as the woodcuts show.

Here is another set of English words becoming fashionable at the time, like “ChecKer boarP,” “DISH,” and “tooth brush.”