The investor’s guide to spotting the signs of a stock market crash

Anyone looking at any of the standard models will tell you that the US stock market is overvalued.

Anyone looking at any of the standard models will tell you that the US stock market is overvalued.

For instance, looking at the benchmark S&P 500, the cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings ratio (created by Nobel laureate Robert Shiller) is higher than any time in history—except during the internet bubble from 1998-2001. (By other metrics, the current market valuation is the highest ever but no matter where you stand on that debate, the fact that we’re comparing the current market to the biggest stock market bubble in history—which ended with a 50% correction—should give you pause.)

Despite the negative consequences, euphoric periods (a.k.a. bubbles) happen again and again. Financial memory is short and new generations discard the lessons of the older. Hope drives herds to follow winners, mistakenly associating money with intelligence. And a fear of missing out drives increasingly extreme behaviors.

The focus of bubbles varies. From tulips in the 1630s, to industrials in the 1920s, to the Nifty Fifty in the 1970s, to the internet in the 1990s, investors have focused too much capital on a single new thing without regard to price or value. Today, it seems to be globally synchronized growth (a fancy way of saying that most economies around the world have recovered from the 2008 financial crisis and are doing well) that has investors convinced that everything is different this time and that the value of everything will just keep going up. And it seems that the new thing may be the S&P 500 with conventional wisdom advising that simply buying an S&P 500 ETF will lead to wealth and life on easy street.

Will this manic moment turn negative and, if so, how bad will it be?

Markets don’t go down because things are expensive. Even though there is a chorus of bears saying that the market is overvalued, there is a louder chorus of bulls who is cheering the market to go higher. The question is whether and when the bull chorus will lose its voice. And whether there will be a crash at the other end.

And not all rapid price increases end in crashes. Research published by Harvard shows (pdf) that the price run-ups that are more likely to crash are accompanied by three criteria that we’ll be watching closely in 2018:

- Increasing volatility. Stock volatility—as measured by the VIX Index—is at all-time lows. But we’re watching for changes in the stabilizing forces that are keeping volatility low such as low interest rates, low inflation, central bank liquidity, and corporate buybacks.

- New stock issues. The number of IPOs (pdf) in the US in 2017 was moderate historically but the number of IPOs around the globe was higher in 2017 than any year since 2007. The expectations for IPOs is high for 2018 and we’re watching for aggressive new issues that indicate market excess whether those be high risk tech companies or quick turnaround private-equity deals like the recent ADT IPO.

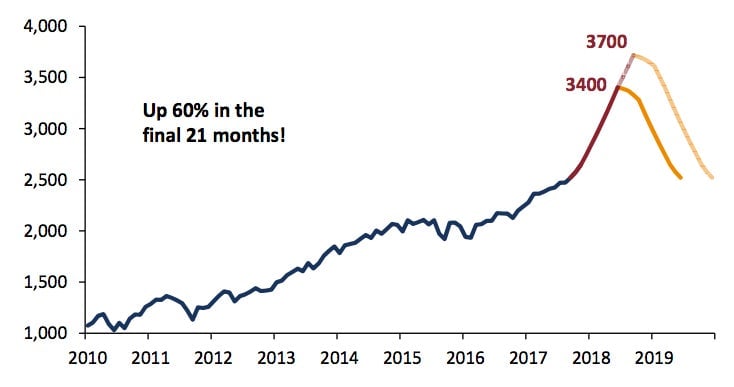

- Accelerating price increases (a.k.a. “melt-ups“). Even though the market is up, it isn’t clear if it is melting-up yet. We have no idea if it will or when. History says that odds are we’re going to see a melt-up soon. But there is no way to predict when since the biggest factor in all of this is human behavior. And no one can predict the behavior of a group of people as large as those in the financial markets.

We’re also watching for indications that the globally synchronized growth story may be coming to an end such as:

- a loss of liquidity due to central bank tightening;

- growth troubles from inflation, demographic shifts, or a troubled consumer;

- a drag from worldwide indebtedness;

- or a desynchronization from a declining dollar.

Any of these issues could spook investors and put an end to the current euphoria. But we could still still see quite a melt-up before any of these larger issues put an end to the current bull market. Jeremy Grantham, the legendary head of investment firm GMO, has predicted that the S&P 500 could rise 20-30% more over the next 9-12 months if it follows the pattern of previous bubbles. Of course, the issue is that timing the top of any bubble is extremely difficult.

So what to do ahead of a possible bubble burst?

Perhaps follow the lead of David Swensen, head of the Yale endowment and one of the most successful investors in history. Swensen has increased Yale’s allocation of investments that don’t move with equities, like US Treasuries, to provide liquidity if there is a correction. This isn’t the first time Swensen has used this strategy. In 2008, he had 30% of Yale’s assets in uncorrelated investments and he used half of that to buy equities when they were cheaper in 2009-10.

How much does Swensen have available today? 32%.