It’s been a spectacular year for the Indian stock markets. But, somehow, corporates aren’t cashing in. This has left India’s chief economic advisor Arvind Subramanian puzzled.

The answer may lie in a report by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), released earlier this month, which shows that Indian companies aren’t fully utilising existing capacity, negating the need to expand.

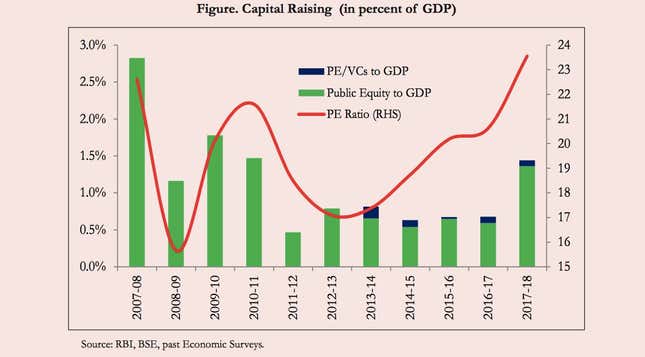

The Subramanian-led economic survey 2018, tabled on Jan. 29, noted that funds raised from the market by firms in the current financial year are set to be double the average amount of the last six years. Yet, even that is lower than the amount raised during the peak of the stock market bubble between 2007 and 2008. This, despite the fact the investors today are willing to pay a record premium for earnings.

“…there has been a similar experience in the US (of limited public offerings) but there is one crucial difference: The US private corporate sector is stashed with cash because of high profits and weak investment opportunities. Firms face a capital feast not famine,” the economic survey 2018 noted. “But this is not the case in India, as firms face significant capital needs, arising from low levels of profit and cash, and high leverage (debt-to-equity) ratios. That is the puzzle.”

It’s possible that a fragment of this capital-raising has shifted to private equity, venture capital, and mergers and acquisitions. But even then, the total capital raised remains relatively muted.

Earlier this month, the RBI had noted that companies are running at only 71% of their actual capacity due to subdued economic activity. With tepid growth in exports and new orders plummeting at this point, raising capital is unnecessary for India’s private sector.

Yet, since the start of this financial year, the Sensex—India’s benchmark equity index—has risen by over 20% and, since December 2015, it has surged by over 46%. Global liquidity and expectations of faster growth in the near future have fuelled this rally. Besides, the note ban in November 2016 also funnelled some cash holdings into financial assets in India.

“The government’s campaign against illicit wealth over the past few years—exemplified by demonetisation—has in effect imposed a tax on certain activities, specifically the holding of cash, property, or gold. Cash transactions have been regulated; reporting requirements for the acquisition of gold and property have been stiffened. In addition, rupee returns to holding gold have plunged since mid-2016,” noted the survey. This has, in turn, led investors to re-evaluate the attractiveness of stocks and realign their portfolios.

The result: a sharp surge in stock valuations. But in the absence of corporate demand for funds, the paradox may well persist.