The Narendra Modi government has cast its tax net wider with the goods and services tax (GST) and added 3.4 million new indirect taxpayers since its launch in July 2017. But most of the new registrants are small businesses beset by the burden of compliance under the new regime, and add very little to the government coffers.

The GST was intended to be a reform that would net thousands of tax-evading businesses. As it turns out, the top 10% of the country’s firms pay 90% of the country’s indirect taxes, according to the Economic Survey 2018 (pdf). And about 1.9 million GST registrants are small firms that account for a very small chunk of the total turnover and tax liabilities.

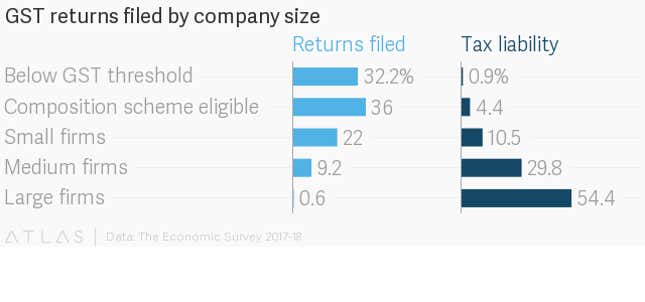

“The registered below-(GST) threshold firms account for 32% of total firms, but less than 1% of the total turnover, while the largest account for less than 1% of firms but 66% of turnover, and 54% of total tax liability” said the survey, authored by a team led by India’s chief economic advisor Arvind Subramanian.

While the new regime allows firms with a turnover of up to Rs1.5 crore ($235,200) to opt for the less rigorous “composition” scheme—an alternative method of taxing smaller businesses—most of them still prefer to register with the GST network. That is because even though firms can pay lower taxes with less complex compliance procedures under the scheme, they are not allowed to avail the benefits of input tax credits, i.e. refunds on the taxes paid on intermediate purchases.

Also, without input tax credits, big businesses refrain from dealing with suppliers under the composition scheme.

“They (the small firms) pay a small tax (1%, 2%, or 5%) on their turnover and are not eligible for input tax credits. This set-up minimises their administrative burden, but also makes it difficult for them to sell to larger firms, which would not be able to secure input tax credits on such purchases,” the survey explained.

This problem persists the other way round as well, wherein smaller firms that buy from large companies are also unable to claim input tax credits unless they register with the network.

“Small businesses need to evaluate the merits of composition scheme vis-a-vis full compliance and input tax credits, and decide accordingly,” Vikas Vasal, national leader for tax at Grant Thornton India, told Quartz. “The compliance cost will increase (for small businesses), but not considerably.”

This cost is a small price to pay for the overall formalisation of the economy. Small businesses registering with the GST network will ensure that the entire supply chain runs more smoothly, according to Vasal.

“It’s clear from the economic survey that many businesses that were on the periphery have now opted for or are being compelled to come within the tax net. A key reason is the overall structure of the GST, wherein the whole supply chain functions smoothly only if all the businesses in the entire chain are tax-compliant,” he said.

Nonetheless, the fact remains that India is far from “one nation, one tax.”

Until the system is fine-tuned, smaller businesses may continue to bear the brunt.