Last week, the video of a question posed to celebrated Nigerian author Chimamanda Adichie by French journalist Caroline Broué, “Are there bookshops in Nigeria?“, sparked a social media furor that went global. Nigerians at home about abroad fumed at the idea that such a question could be asked in the first place.

Unsurprisingly, Adichie, who has a well-earned reputation for not tolerating ignorance about Africa, did not take kindly to the question either and responded (or “clapped back” to use the slang) saying the question “reflects very poorly on French people.” In a later post on Facebook, Adichie was critical of the “deliberate, entitled, tiresome, sweeping, base ignorance about Africa.”

While there was some ignorance on the journalist’s part and some misunderstanding on Adichie’s part (as she later admitted), there’s a conversation to be had about bookshops in Nigeria. Do they exist? Yes. Are there enough of them? Not even close.

Lola Shoneyin, a popular author and also convener of the Aké Arts and Book Festival, the leading annual literary event in Nigeria, says the social media furore was “a lost opportunity to have an important conversation around bookshops” and issues publishers and authors face. The biggest problem remains distribution.

“For a country of our size, the number of bookshops is abysmal,” Bibi Bakare-Yusuf, co-founder of Cassava Republic, a Nigerian book publishing company, tells Quartz. The lack of bookshops is particularly frustrating for publishers looking to distribute their titles. Unlike educational publishing companies that focus on producing textbooks and marketing them to a steadily available market of school students, publishing companies like Cassava Republic target a broader market and face a distribution challenge. Cassava Republic, which is one of the success stories of African publishing in the last decade, can list just 33 bookshops across ten states in Nigeria where its books are available.

Eleven of those bookshops are in Lagos, Nigeria’s largest city. While there are no accurate figures for the total number of bookshops in the city, Cassava Republic’s distribution chain is indicative of the dearth of bookshops in a city of 21 million people. In comparison, New York has 840 bookstores for its 8.4 million people while London, with 8.7 million people, has 360 stores based on 2015 estimates.

Crucially, with bookshops in existence mainly being independent entities with single outlets rather than chains across the country, publishers face the “challenge” of having to deal with multiple dealers, Enajite Efemuaye, managing editor at Kachifo Ltd., says. “If there were chains, distribution would be easy because you are dealing with just one entity.”

Given that these independent outlets mushroom in urban city centers, there are major gaps across the country perhaps most significantly in northern Nigeria where literacy rates are low. While large independent bookshops have hardly expanded, Bakare-Yusuf says having bigger book sections at cafes and shopping marts is a growing trend which offers more visibility for books.

Like many industry sectors in Nigeria, the collapse of the book sector really took hold over the last 20 years. A steady slump in Nigeria’s naira currency has been critical for bookshops and publishers alike. As a result of the high costs of importation and production abroad (for publishers), books are often too expensive for the average Nigerian, Shoneyin says. Consequently, the decline of local bookshops, compared to the 1970s and 1980s, has been sharp. Another reason for this, Efemuaye says, is the fading away of university bookshops which drove literature and book culture in yesteryear.

“Even though there are more universities, there are not enough functional university bookshops,” she says. Even worse, public libraries have nearly gone extinct in Nigerian cities owing largely to a lack of funding—and attention—from the government. The current reality betrays Nigeria’s rich literary heritage having produced world renowned literary icons such as Chinua Achebe and Wole Soyinka, the first African to win the Nobel Prize in Literature.

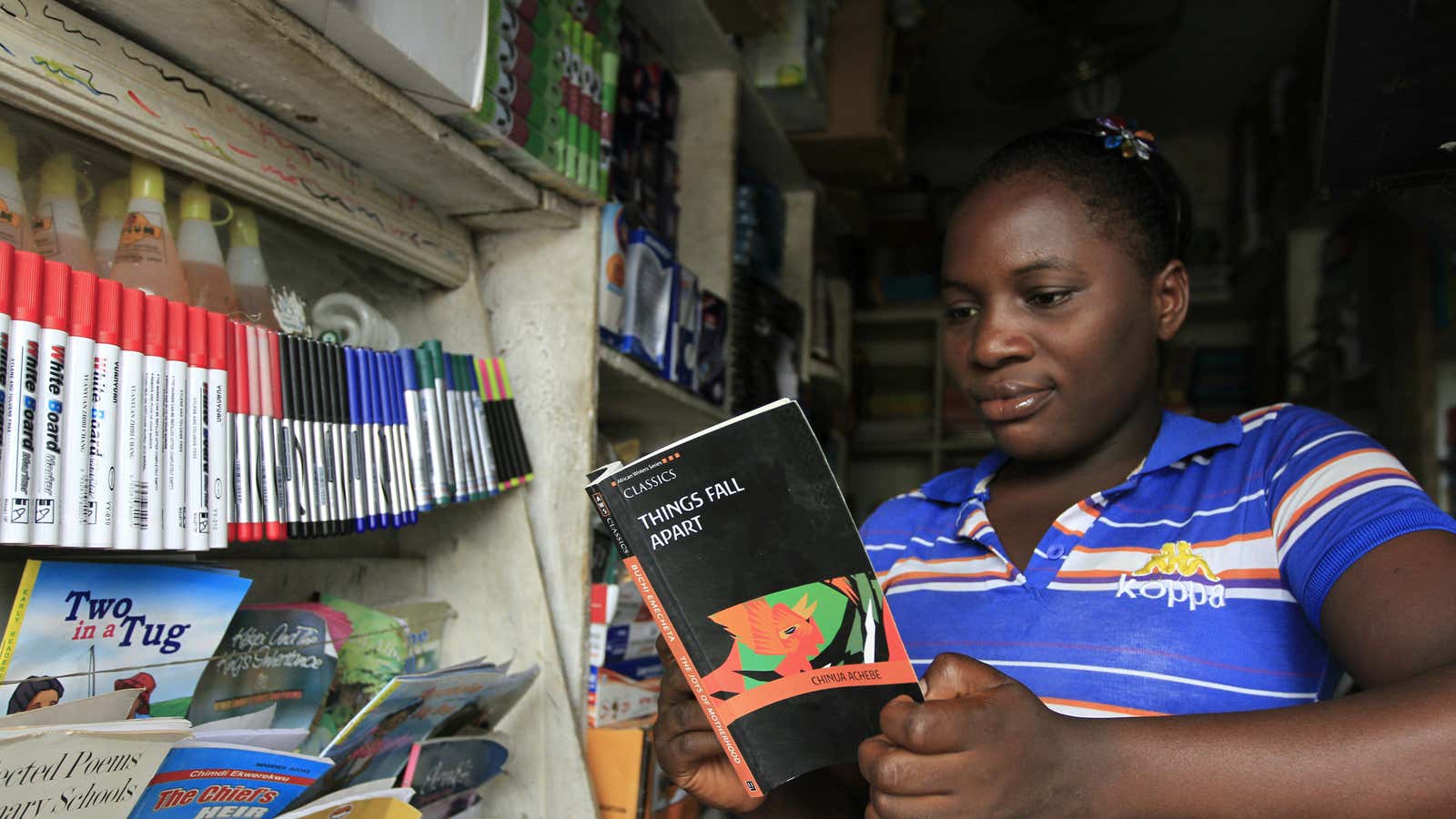

But even though there aren’t many large Western-style bookshops, Shoneyin says a possible solution to the distribution problem could be plugging into the large informal sector of sorts comprising of smaller book stalls in local markets and roadside sellers (which mainly deal in second hand books) that still exists.

Going online

An alternative for book distribution in recent years has been listing books on e-commerce sites as well as the emergence of online book stores given increased access to the internet amid dropping data prices with more people potentially able to order books. But Efemuaye suggests the accompanying delivery charges often discourage buyers.

Okada Books, one of such internet-powered alternatives was created by Okechukwu Ofili, a 2016 Quartz Africa Innovators honoree. Launched as a mobile app, users buy e-books and pay with bank cards or airtime. Since its launch in 2013, Okada Books has notched over 100,000 active users and has sold over 17,000 books. Ofili says he started the company because of the distribution problem publishers and authors have faced as the number of bookshops in Nigeria is “ridiculously low.”

For her part, Bakare-Yusuf admits that the internet and social media have “promoted book discovery.” However, the internet poses its own unique piracy problem. Shoneyin says she frequently gets requests for free PDF copies of her books. Perhaps in the best known example of the piracy issue, two years ago, a massively promoted book authored by a popular media personality was widely available on WhatsApp in PDF format the day after it launched.