Evidence continues to mount that refugees deported by Israel to third countries in Africa face grave dangers and death, including risking their lives by taking perilous onward journeys to Europe.

Asylum seekers removed under the “Voluntary Departure” policy to countries like Rwanda and Uganda were deprived of their official documents, exposed to extortion, threats, and imprisonment, and in some cases, even forcibly returned to the nations they originally fled, according to new report by three independent researchers and published through the advocacy Hotline for Refugees and Migrants.

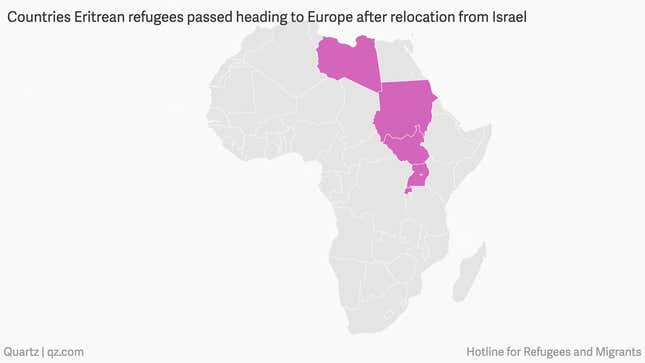

The study was conducted with 19 Eritreans who were relocated between 2014 and 2016, only to leave East Africa again and be granted refugee status in Germany and the Netherlands. Their testimonies showcased the multiple traumatic experiences they were exposed to as they traveled through conflict zones in South Sudan, Sudan, and Libya.

The study’s findings reinforce recent conclusions reached by the United Nations, who have warned of the precarious shortcomings of this policy and its consequences for those “voluntarily” departing. Since 2013, Israel has proposed several measures aimed at making the lives of African immigrants “miserable” including incarceration and prevention of work permits and welfare services. Under the “voluntary” repatriation programs, the government also transferred almost 4,000 Eritreans and Sudanese back to countries in sub-Saharan Africa, a move decried by human rights organizations.

The deportations have also taken on a renewed urgency in recent months, as the Middle Eastern nation stepped up efforts to expel the “infiltrators” even without their consent. In early January, the government publicly stated it would help immigrants purchase tickets, obtain travel documents, and give them $3,500 to leave—threatening them with arrest if they are caught after the end of March. As public scrutiny and global criticism of the plan intensified, officials said they would hire civilian immigration inspectors for two years to help investigate and arrest African refugees. Amid the increasing opprobrium, Rwanda and Uganda both denied that they had struck any deals with Israel to receive the refugees.

Shani Bar-Tuvia is a doctoral candidate at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, who analyzed the deportation policy’s implication in the report. She says the government’s intention to use secret agreements, forcibly remove immigrants after having lived in Israel for many years to countries other than their homelands, while recognizing that they do come from dangerous territories to which they cannot be returned, raises serious legal and moral qualms.

“The policy is highly problematic. You don’t need to be a legal scholar to understand that this is wrong,” she said.

In Uganda and Rwanda, the Eritreans were robbed of their money and fell into the hands of smugglers who sold them to traffickers in South Sudan. In Juba, they were detained for months for lack of documentation before fleeing to Sudan. There, the threat of being returned to Eritrea was evident, with some of their fellow travelers succumbing to it. The dread of returning to where they fled from pushed many to traverse the Saharan desert and cross the Mediterranean Sea from Libya to Italy.

Many of the interviewees said the beatings, death of friends, and the violence they encountered on the road scarred them, pushing them to seek psychiatric assistance in their host nations. “At night it comes to us in our head, it repeats,” one refugee identified under the pseudonym Kiflom said. “I don’t want to remember this… I want to close that door.”