If everything goes according to plan, Nigerians will be going to the polls to elect a president almost precisely a year from now, on Feb. 16 2019. As always with most election seasons, permutations are underway as to who the major players might be, how campaigns will be run and which candidates stand the best chance. In Nigeria, election season is about to get into full swing.

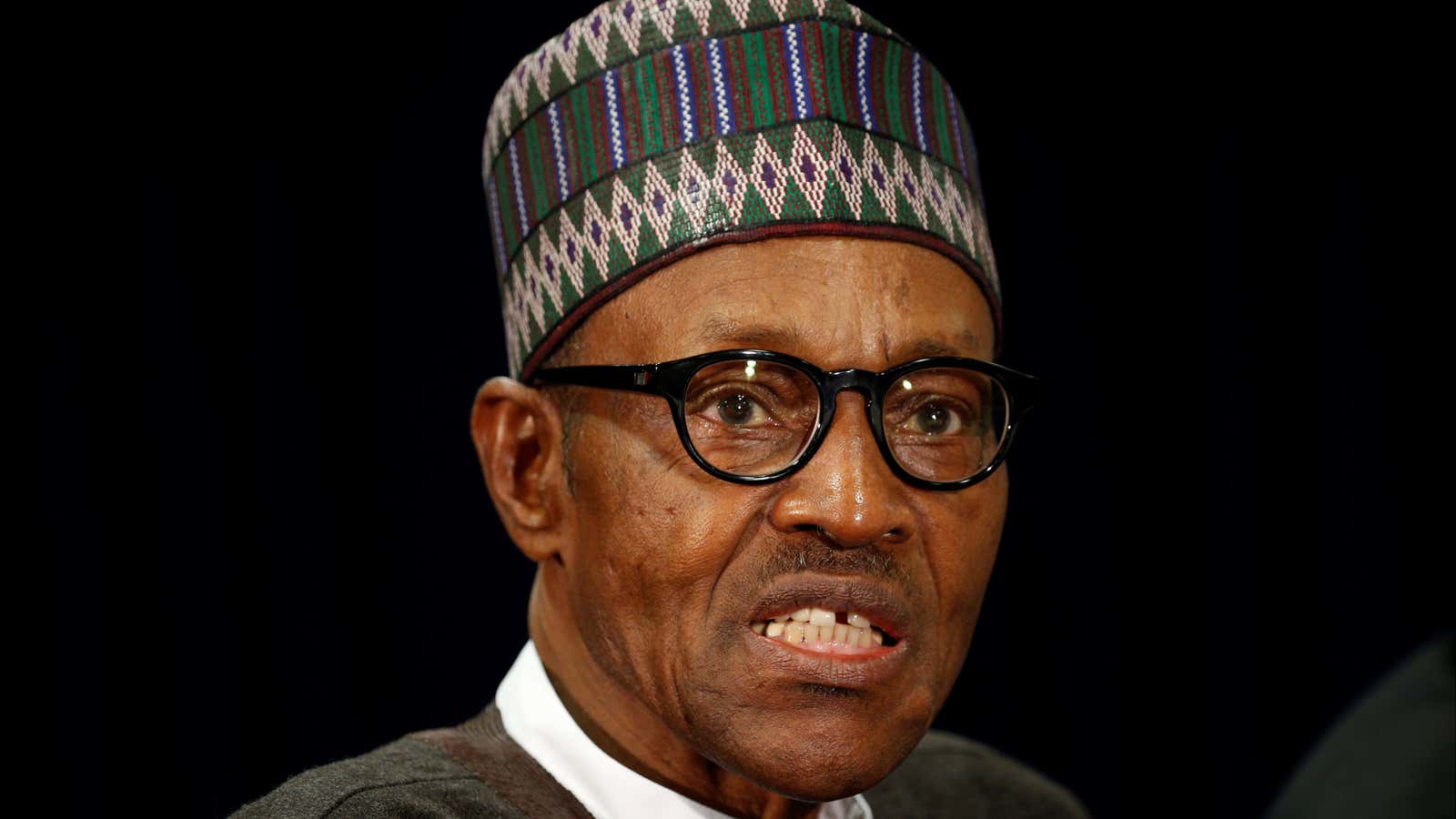

President Muhammadu Buhari, 75, will have the advantage of incumbency which, in Nigeria, is not to be taken lightly. Since 1999, when Nigeria returned to civilian rule, a sitting president has lost at the polls only once. It happened in 2015 when Buhari’s All Progressives Congress (APC), succeeded in defeating then-incumbent Goodluck Jonathan of the People’s Democratic Party (PDP). It was Buhari’s fourth run for the presidency and snagging that election win was far from easy. It required a complex and uneasy marriage of several political parties and interests.

One year before the next election, the alliance is holding despite cracks that have since appeared and even though neither president Buhari nor the APC have confirmed his re-election bid, some indicators suggest one might be on the cards. Close allies of the president have began talking up his chances while APC has began appointing key campaign officials in parts of the country.

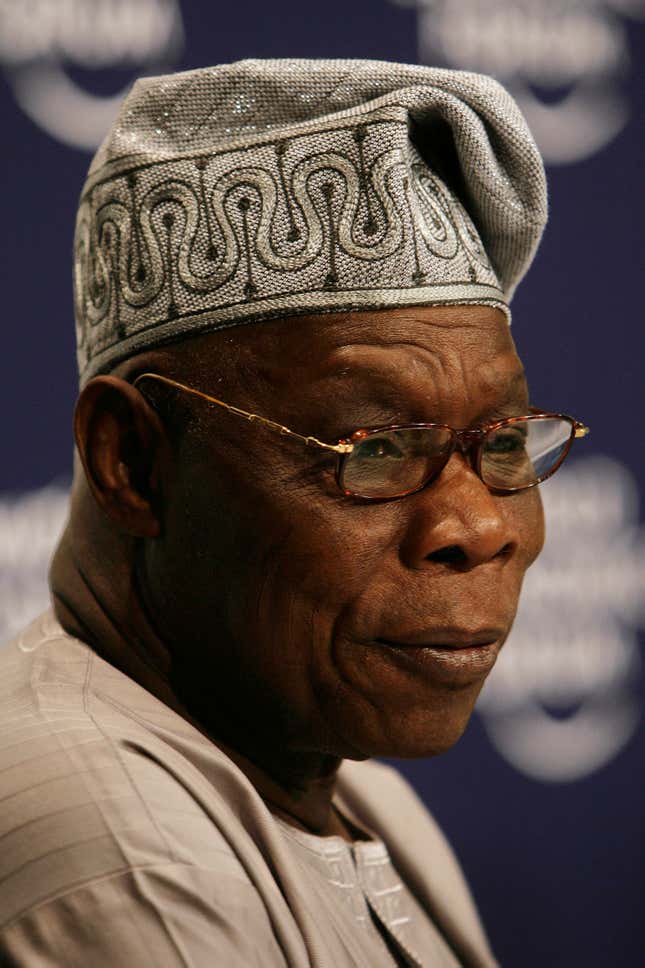

But while the president seems undecided, he’s already facing high-profile opposition. In a 3,500-word open letter published in national dailies, Olusegun Obasanjo, Nigeria’s president from 1999 to 2007, pointedly asked Buhari not to seek re-election citing his weakness in “understanding” the economy as well as foreign and internal affairs. Some of the opposition to Buhari’s re-election bid has come from within his party. Even closer to home, Aisha Buhari, the first lady, has retweeted messages which criticized the president and suggested he’s not in control of his government.

Gone full circle

Three years after becoming president, Buhari appears to have gone full circle and finds himself in the same position as Goodluck Jonathan, his predecessor, during the last elections. Despite enjoying lots of goodwill when he took office, like Jonathan, Buhari’s popularity has significantly waned. Buhari will also face scrutiny over his handling of Nigeria’s security crises.

But the toughest questions will be about his handling of Nigeria’s economy. Under his watch, the economy slipped into its first recession in nearly two decades in the first quarter of 2016 and went on to suffer a full year of shrinkage. Unemployment has also spiked: between the third quarter of 2015 and of 2017, the official unemployment rate nearly doubled. While much of the crisis was triggered by the drop in oil prices, analysts also partly blamed it on Buhari’s policies, such as his initial stubborn refusal to devalue the naira currency only to do so months later.

The government has recorded some success in making it easier to do business in the country with Nigeria improving by 20 places in the latest Doing Business report. It has relaxed visa entry rules for foreigners and investors, launched reforms at local ports to boost trade.

It has also made it easier and cheaper to start businesses. But the government has not shown a similar appetite for reforms elsewhere. The lack of political will to deliver big-ticket reforms while oil prices were low and provided an incentive to do so, including deregulating the petroleum sector, represents a missed opportunity. To compound the problem, several Nigerian cities have been plagued by intermittent fuel queues since December. It’s also unlikely that the government will be taking on any risky reforms at the expense of political expediency with the elections around the corner.

Like his predecessor, Buhari also faces questions over his handling of security problems. Under his administration, Nigeria’s army has markedly gained the upper-hand in the high profile battle against Boko Haram, securing the release of abductees and wining over vast swathes of territory in the northeast. But elsewhere, other problems have worsened as festering tensions between nomadic herdsmen in Nigeria’s north and farmers have violently come to the fore. Over the years, a loss of grazing land due to desertification and a lack of rainfall has forced herdsmen to head south for fertile grazing land usually owned by farmers in the region. In January alone, over 70 people were slaughtered in a single incident and last year, rampaging herdsmen were deemed a bigger security threat than Boko Haram. Buhari has been criticized for a tepid response not at par with the gravity of the situation.

In contrast, in Nigeria’s southeast, Buhari appears to have responded to agitations for secession by the Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB) almost too gravely. Last September, an army siege in the region reportedly left four IPOB members dead. Nnamdi Kanu, the leader of the group who faces charges of treason, has not been seen since the siege.

Away from his performance, there’s also the question of Buhari’s fitness and health. Last year, he spent over 150 days in London on medical leave receiving treatment for an undisclosed illness. Since returning, the president has missed some cabinet meetings while the administration remains tight-lipped about his health. If he chooses to run again, how he copes with what will likely be a long and tasking campaign schedule will be closely watched.

New fronts and old faces

Nigeria’s young electorate (the median age of the country is 17.9) is hopeful of voting in a younger president (between 40 and 50 years old) in 2019. But that’s unlikely as even though Nigeria is a multi-party state, neither APC nor PDP, the two most dominant parties appears interested in fielding a young candidate.

Despite PDP’s 16-year reign in office, much of its time as an opposition party has been rocked by in-fighting. It took a court judgement in July 2017 to resolve the party’s leadership disputes. Regardless, it remains a formidable party with several former and current public office holders.

Ahead of the elections, PDP could benefit from a culture of political flexibility that has characterized Nigerian politics. In 2015, the party was weakened as several members switched allegiances to APC which had notable momentum at the time. Yet it could benefit from a similar scenario with murmurs of discontent in APC gaining steam. Atiku Abubakar, vice-president between 1999 and 2007 and three-time presidential candidate, has led the way, leaving APC for PDP in December.

Buhari’s re-election campaign, like the previous ones, will run on his long-running, well-oiled anti-corruption campaign rhetoric but it’s one that has taken a beating with corruption scandals involving highly-ranked officials of his administration. Cheta Nwanze, head of research at SBM Intelligence , an Africa-focused geopolitical analysis firm, says the president will have little choice regardless. “He really cannot run based on performance,” he tells Quartz. “The numbers speak against him.”

If he chooses to run, a Buhari victory will strongly depend on maintaining an accord with party chieftains in Nigeria’s southwest. The president, a northerner, has always been very popular in northern Nigeria, but that alone has never been enough to get into office as he realized in 2003, 2007 and in 2011. In 2015, Buhari had more appeal—and won more votes—largely thanks to the APC’s strong national presence especially in the southwest.

Buhari’s popularity in the north is such that if he chooses not to contest, he will still play a pivotal role in the elections by throwing his weight and popularity behind APC’s candidate. But with his plans for the election still under wraps, presidential hopefuls in the party are keeping their cards close to their chest. Should he choose not to contest however, there’s a slim chance vice-president Yemi Osinbajo might be the party’s ticket-bearer. He’s already won plaudits (paywall) during his stint as acting president while president Buhari was away on medical leave.

But there are some who have grown tired of APC and PDP’s duopoly of political power. Former minister of education and longtime activist, Oby Ezekwesili has started a “red card movement” campaign to drum support among Nigerians for parties other than PDP and APC while Obasanjo has also started a Coalition for Nigeria Movement looking to present a viable third option. Stanley Azuakola, publisher of The Scoop, a policy-focused news website, says that, like PDP, Obasanjo is “betting” on bringing disgruntled members from both parties seeking a new platform into his fold. Put another way, the coalition will likely be a new front for old faces.

As elections and permutations go, a lot can happen in a year. In Nigerian elections, that pretty much comes with a guarantee—a lot is bound to happen.